July 23 to July 29

Koo Chen-fu (辜振甫) only discussed the incident once in public. It was May 1993, and firebrand Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) legislator Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) had been criticizing him publicly for months in a bid to try and stop the then-Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF, 海峽交流基金會) chairman from meeting his Chinese counterpart Wang Daohan (汪道涵) in Singapore.

After the conclusion of what would later be known as the historic Koo-Wang Talks, Chen continued to question Koo, finally bringing up the subject Koo had preferred to avoid: his sentencing in 1947 for his involvement in the “Plotting Taiwan Independence Incident” (謀議台灣獨立案), where he was accused of working with Japanese officers to create an independent Taiwan after Japanese surrender and before the arrival of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

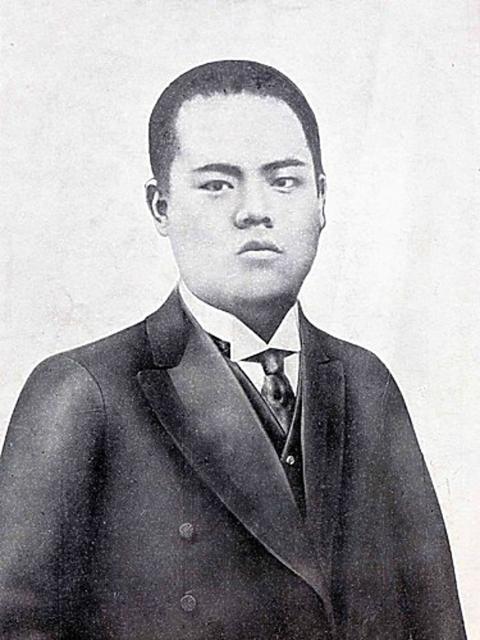

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chen’s camp had been trying to paint Koo, a long-time KMT member, as a traitor to the country, even calling out his late father, Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮), who invited Japanese troops into Taipei in 1895 after local resistance had crumbled and the city had descended into chaos. Some say he was being opportunistic, others say he did it to restore order and prevent further violence. Regardless, the family worked closely with the authorities and prospered under colonial rule.

Chen’s questioning about the 1946 incident finally rattled the usually stoic Koo.

“What’s so dishonorable about serving a groundless sentence? Is that betraying the country? It’s already unfair that the government never cleared my name. Today I have to suffer this treatment in the legislature. This is completely unjust!” he shouted.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

POST-WAR SENTIMENT

After Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, the colonial Office of the Taiwan Governor-General reported that while most Taiwanese would likely accept Chinese rule, there were some who would worry about being treated as Japanese collaborators. Others were concerned about the KMT’s ability to rule properly. In response, the office instructed the police to focus on maintaining order, collecting information and to “decisively suppress all signs of scheming for Taiwanese independence.”

These feelings were not unusual. For example, Hsinchu assemblyman Huang Wei-sheng (黃維生) believed that he would have a better chance of surviving and preserving his property under an independent Taiwan approved by Japan, and made a petition to the local government. Yang Kui (楊逵), a novelist and anti-Japanese activist, also expressed his distaste for the KMT’s “reckless and brutal ways” in China, but the colonial reports note that “he was not of much influence.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Rikichi Ando, Japan’s final governor-general in Taiwan, reportedly told the independence petitioners that “I understand your sentiments for Taiwan independence. But looking at the bigger picture, for your sake, I suggest that you cease such activities. If you insist on proceeding, I will have no choice but to request the Japanese Army to suppress your movement.”

The sentiment faded quickly, however, as by September, colonial reports show that most of the population were preparing to welcome the arrival of the KMT. The Minpao (民報) newspaper ran an editorial in October of that year comparing independence activists to Qin Kuai (秦檜), a notorious figure in the Song Dynasty who is regarded as a traitor.

GUILTY OR NOT?

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The KMT arrested Koo and four other alleged independence petitioners in February 1946. On July 29, 1947, they were convicted of sedition. Koo received the longest sentence of over two years.

“Most people are overjoyed about the return of Taiwan to the motherland,” the verdict states. “But Koo Chen-fu and his accomplices leaned toward Japan, and were one of the few who lamented Japan’s loss.”

The verdict states that several Japanese officers who refused to accept surrender instigated the incident and recruited Taiwanese to join in their plan, which was only stopped after Ando made his warning.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The so-called self-rule movement was started by the Japanese and would benefit the Japanese,” it continued. “This is essentially sedition under the guise of self-rule. We have sacrificed so much to fight the Japanese and liberate the people of Taiwan, yet these people are not only not grateful, but succumbed to Japanese influence.”

The reason for the relatively short sentences are revealed by the following: “Considering the fact that the Japanese are the instigators and the defendants have been brainwashed by the Japanese, their actions are somewhat forgivable.”

However, later interviews with former Japanese military officials in Taiwan show them insisting that they had nothing to do with the independence attempt.

Koo has long maintained his innocence, claiming that he actually tried to stop the attempt and the sentencing was punishment for the Koo family’s close ties to the colonial government. The son of Hsu Ping (徐丙), another defendant, also declared his father’s innocence. His version of events state that Hsu’s close associate Lin Hsiung-hsiang (林熊祥) angered then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) by demanding that he repay an overdue loan, and Chen arrested him and his friends as revenge.

Due to the lack of evidence, the truth is still unclear. However, Japanese records clearly state that Lin Maosei (林茂生) and other “Taiwanese elite” did make an attempt at independence right after Japanese surrender. Lin “disappeared” in the aftermath of the 228 Incident, leaving nothing behind that proves whether Koo and the other defendants were involved.

An interesting footnote to the story: While Koo Chen-fu became a KMT loyalist despite his alleged independence attempt, his half-brother Koo Kwang-ming (辜寬敏) is a DPP member and lifelong Taiwan independence activist.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry