July 16 to July 22

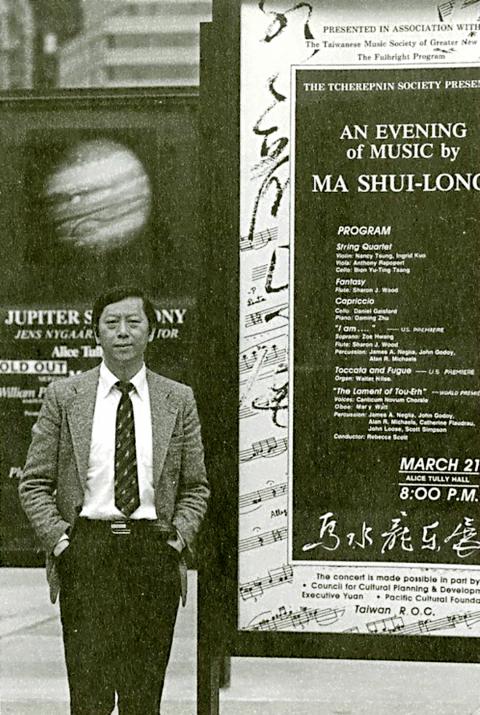

The news was mostly overshadowed by the 22nd Golden Bell Awards, but on March 21, 1987 Ma Shui-long (馬水龍) became the first Taiwanese composer to have his work performed at New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

Some sources — including his biography, Musical Maverick: Ma Shui-long (音樂獨行俠馬水龍) — maintain that he was the first composer from the Far East to have a solo show at the prestigious performance hall. However, the honor only received a brief mention in the Central Daily News (中央日報) entertainment section under the title, “Composer Ma Shui-long debuts new material today in the US.”

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Music Institute

Born on July 17, 1939, Ma was just 47 years old.

FUSING EAST AND WEST

Despite the newspaper headline, it appears that just one of the six songs in the program was new — an adaptation of a Yuan Dynasty play, The Injustice of Dou E (竇娥冤), which featured only vocals, suona horn (嗩吶) and a variety of percussion instruments. The study, When Tradition Becomes Modern (當傳統成為現代), notes that while the song is deeply rooted in Eastern traditions, Ma took many liberties to modernize it.

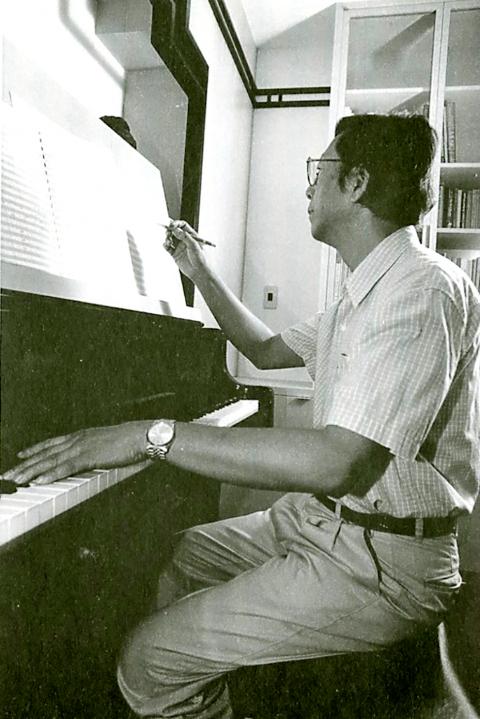

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Music Institute

“The chorus provides a rich layering that’s often missing in traditional Chinese music. The composer’s decision not to use lyrics may have been for the convenience of the performers and for those in the audience who didn’t understand Chinese. But not only has it erased language barriers, it also removes the barrier between voice and instrumentation,” the study states. “Perhaps the combination of suona and chorus can serve as an example of the fusion of East and West.”

Ma’s unique approach earned him praise from notable New York Times music critic Bernard Holland two days later.

Holland writes that Ma “balanced the largely conventional use of Western instruments with the pure intervallic skips and pentatonic melody from his own culture — and it did so without descending into the usual cloying chinoiseries.”

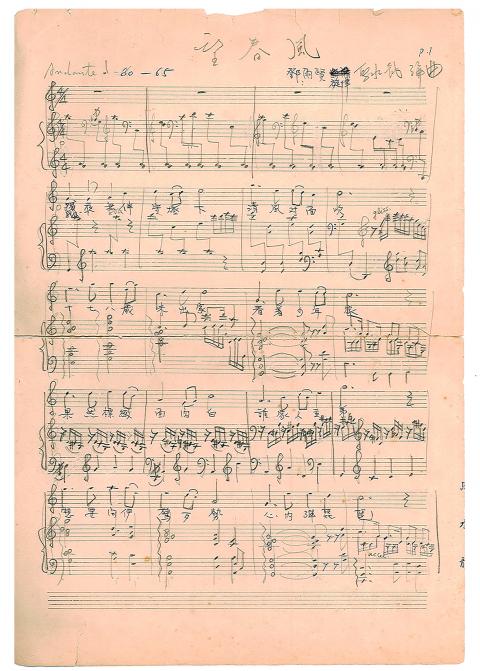

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

“How does he do it? Partly by letting his instruments speak in a European voice but with an Asian mind.”

In addition to Chinese classics, Ma also rearranged Taiwanese folk songs such as the classics Yearning for Spring (望春風) and Mending the Net (補破網). He also composed his own Taiwan-inspired material such as Thoughts of Kuandu (關渡隨想) as well as the score for Cloud Gate Dance Theatre’s 1979 production Liao Tien-ting (廖添丁), a performance about the legendary anti-Japanese “Robin Hood” of Taiwan. He expanded the latter into an orchestral suite in 1988.

As a music professor, Ma strongly believed that cultural preservation and protecting traditions was an “inescapable responsibility,” according to a brief biography by the National Central Library. He would frequently warn his students that while learning Western instruments, theory and techniques, they should not forget their origins, insisting that each student learn at least one traditional instrument.

“He was not anti-Western, but he did not want to see music, or even culture in general completely lean toward the West. He also was a proponent of ‘world music,’ which he thought could loosen Western music’s dominance,” the report stated.

ROAD TO NEW YORK

Ma grew up in the coastal towns of Keelung and Jiufen, and in the 2008 essay, My Musical Journey of Composition (我的創作心路歷程), he notes that his biggest influences remain the classical beiguan, nanguan and Taiwanese Opera he was exposed to in his youth.

Like many Keelung boys, Ma enrolled in a vocational high school that would prepare him for a maritime career. However, fate changed when his father became ill, causing him to drop out and find work as draftsman at a fertilizer factory. One of Ma’s coworkers was future musicologist Lee Che-yang (李哲洋), who encouraged him to pursue his passion in art and music.

After his father’s recovery, Ma enrolled in the composition department at National Taiwan University of the Arts and began his musical journey. After teaching for several years, he received a full scholarship to study at the Regensburg Music Academy in Germany.

“During this period, all I learned was Western musical theory and methods for Western composition. Although these lessons provided me the requisite knowledge and skills for composition, they hardly fulfilled my expectations for expressing musical aesthetics and philosophy,” he writes.

“To be able to compete with Western musicians on the international stage, we must use our own musical language. What else do we have?”

In 1986, Ma earned a Fulbright scholarship to spend a year in the US as a visiting scholar. During a gathering, an American scholar remarked that Easterners are eager to learn about the West. “That is great. But when you’re getting to know about us, why don’t you let us know about you?”

These words lit a fire in Ma’s heart, and he was determined to have his work performed in the US. Not just any venue — he had his sights set on the Lincoln Center. Although people told him it was just a pipe dream, he managed to make it happen with the help of The Tcherepnin Society, a non-profit dedicated to promoting music.

That night, the concert hall was packed — not just with local music aficionados but also a large contingent of Taiwanese Americans who came to show their support. The concert’s success led to three more shows in Washington DC, San Francisco and Los Angeles, by far exceeding his original goal.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had