As long as Kristin Chang (張欣明) can remember, her mother has attributed her likes, dislikes, dreams and phobias to past lives. A Buddhist, her mother raised Chang with constant reminders of reincarnation: Chang’s love of cats was a sign that she had once been one; her love of New York City meant that, in a past life, she must have been a New Yorker.

WEIGHED DOWN PAST

Burdened by these legacies, Chang longed for a childhood with Western sensibilities — the individualistic, self-reliant culture she witnessed everywhere in her hometown of Montebello, California. Instead, her Taiwanese immigrant family brought traces of their past to the US.

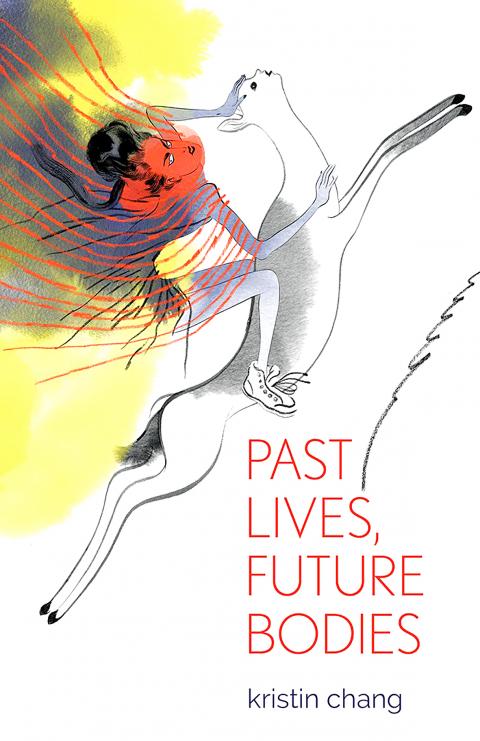

Photo courtesy of Kristin Chang

“I used to think that the very idea of reincarnation stripped me of my agency,” Chang, 19, says. “As if I weren’t a real person, just a collection of past lives; like cats and New Yorkers.”

She fought the label, adopting Christianity and dismissing her mother’s faith.

As an adult, though, Chang feels grounded in her mother’s reincarnation myths, making it a central theme of her debut chapbook, Past Lives, Future Bodies , which will be published in October by Black Lawrence Press. The book seeks to reconcile her origins, both in this life and past ones, and embraces the yet-unknown. In the process, Chang reckons with her family’s experiences.

Chang’s writing did not always serve as such an overt tribute to her roots: as a younger writer, she felt the urge to distance herself from her heritage, in writing as well as everyday life. Feeling removed from her Taiwanese roots, she often aspired to writing like the white American mainstream she read at school.

“The more I wrote like this white edgy hipster, I realized this was another version of colonizing language,” Chang says. “And I felt like an impostor. I realized that I wanted to be a part of another canon of voices, one that I can identify with.”

ASIAN-AMERICAN DIASPORA

For her, poetry has also helped navigate what it means to be part of the Asian-American diaspora, a larger community which transcends her identity as a Taiwanese-American.

“Being Asian-American is an important political choice for me,” she says. Despite the inorganic nature of the label, which has few cultural commonalities, it has become a way for her to connect with other writers who explore the same diaspora.

In centering the Asian-American community, she joins a host of contemporary poets dealing with strikingly similar identity struggles. Acclaimed poets like Ocean Vuong, Cathy Park Hong and Chen Chen have begun to form the canon Chang envisioned when she first began to break away from the white American literary establishment.

For a writer who places Taiwan at the heart of her authorial identity, Chang is surprisingly distant from her relatives’ home country: she has only been to Taiwan once, years ago. As a result, Chang sometimes feels like an stranger in her own heritage, too removed from Taiwanese culture to participate in it.

“There’s a degree of separation that can seem daunting at times,” she says.

Her primary knowledge of Taiwan comes from an amalgamation of family stories and recollections of her only visit. She preserves this patchwork Taiwan carefully in her poems, using her writing to imagine herself in it.

“In Taiwan the rain spits on my skin. / I lose the way to my grandmother’s / house, eat a papaya by the side of the road,” she writes in her Pushcart Prize-winning poem Yilan.

Chang’s persona seems intimately comfortable with Taiwan, despite her alienation from it.

As with any myth, though, her construction of Taiwan is off-color, not quite reaching the truth. In Yilan, Chang describes herself as watching a typhoon from the 65th floor of a Marriott; “smaller buildings lean / like thirst to water” in her invented narrative. But in the real Taipei, there are no 60-floor hotels.

Chang knows that her experience of Taiwan is distanced through a filter of Asian-American identity and diaspora.

“I try not to write from a purely autobiographical place,” she says, pointing to her descriptions of her parents and grandparents peppered throughout her narrative.

As Chang embraced her mother’s reincarnation myths, her poetry similarly serves as a reclamation of identity. Using secondhand stories of a country she has never known herself, she carves out a new Asian-American mythology of her past lives and future bodies.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern