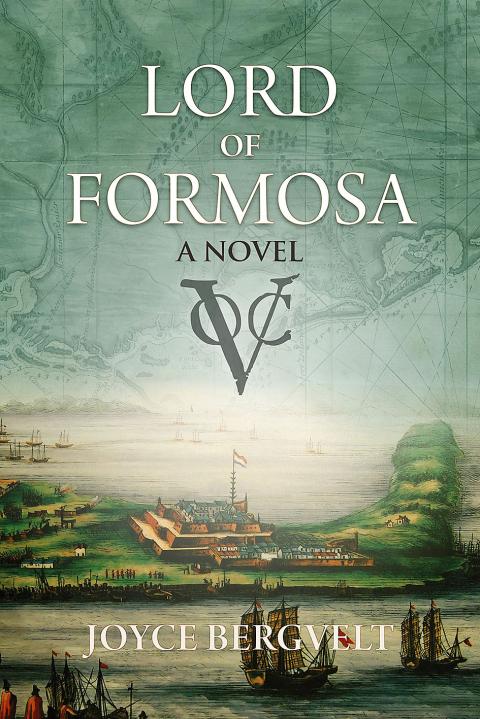

Chinese war junks with crimson sails, diets said to influence the sex of a child and match-makers with painted white faces and red cheeks: Lord of Formosa, which centers on the life of the 17th century warrior and Ming Dynasty loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga), is crammed with these details. I had no idea his life was going to be so fascinating.

Koxinga was brought up as Fukumatsu in Japan’s Nagasaki, with a Japanese mother and a Chinese Hakka father. His father, Zheng Zhilong (鄭芝龍), soon returned to his native Fujian Province, however, where he was the lord of a large estate. When the boy was seven he was ordered to go to China to be brought up as Zheng’s heir, with the Chinese name Zheng Sen.

He was initially frowned on by Zheng Zhilong’s Chinese wives and concubines, a situation made no better by the eventual arrival of his Japanese mother. Things improved, though, after the boy began to display his military prowess, not to mention his enthusiasm for nubile girls.

His father had meanwhile made a reputation for himself as the pre-eminent merchant operating between Taiwan and China. The Dutch had appeared on the scene, establishing themselves in the south at Fort Zeelandia (today’s Tainan), and Zheng soon became obliged to base his operations in the Pescadores (today’s outlying island of Penghu) — technically under Beijing’s control, which Taiwan as a whole was not.

The first part of the novel is largely taken up with his exploits, notably two sea battles with the Dutch; the first battle he loses, the second he wins spectacularly.

The junior Cheng was also involved with supporting the Ming Dynasty, which was under pressure from the Manchus to the north, and now ailing after 300 years of glory. The Manchus, with their outstanding ability on horseback and their archery skills, and in spite of their bulky, greasy queues, were in the process of taking control of China. Zheng Senior, with his naval supremacy, was the main obstacle they faced in the south.

The climax of his fortunes came in the 1640s when the discontented Chinese in Taiwan, who had to pay taxes to the Dutch whereas they’d never had to pay any to China, combined with the authorities in Fujian Province to come to his aid. This proved to be Zheng Senior’s finest hour. But worse, much worse, was to follow.

The embattled Ming emperor, Longwu, had rewarded the Zheng family with, among other things, an honorific name, Koxinga, for their young son. The father, though, had other ideas. The Ming were a lost cause, he decided, and indeed Longwu only reigned for a year and was eventually beheaded. So Zheng Zhilong, fearful that his trading empire would disappear, decided to switch sides and offer his services to the Manchus, by now approaching his family estate at Anhai in Fujian.

Koxinga was appalled by this betrayal, and when the Manchus, represented by one Prince Bolo, learned that the son wasn’t joining his father in switching sides, they lost all faith in Zheng Zhilong, arresting him and taking him to Beijing as a prisoner. His estate was then sacked, the women raped and his Japanese wife ended her life hanging from a tree.

Koxinga wasn’t present to witness these atrocities but, when he eventually saw the devastation, his enmity for the Manchus reached new heights. With this, the first part of the novel concludes.

It’s impressive to discover that the author now goes on to display an equally detailed knowledge of the personalities in the VOC, or Dutch East India Company, based in Batavia (now Jakarta), as well as its personnel on Taiwan.

The failed 1652 rebellion against the Dutch is described, followed by the visit of the top Dutch physician to Taiwan to treat Koxinga, by now effectively the ruler of all of southern China not held by the Qing (the Manchus). Koxinga is shown as afflicted, not only by a skin inflammation that refuses to heal (the author, saying the evidence is inconclusive, risks calling it syphilis), but also by onsets of a rage that causes him to see the world through a red haze and leads him to murder with his own hands any subordinates who have failed in their mission.

Koxinga now engages in a trade war with the Dutch, and almost simultaneously receives news of his father’s and his family members’ deaths at the hands of the Manchus in Beijing. By a final wish, however, Zheng Zhilong hands his son his massive fleet, long disguised as mere trading vessels, giving him the largest naval force ever seen on Chinese waters.

On April 21, 1661, with the Dutch distracted by the possibility of taking Macao from the Portuguese, a fleet of 900 warships and 25,000 men cross the strait to Taiwan. Thus ends the book’s Part Two.

It would be unfair to disclose any more of the plot, other than to say that Koxinga expels the Dutch and dies of his longstanding illness at 38. But what can be said is that this very fine novel is as awash with as much researched detail as it is with vividly imagined scenes. Koxinga himself is generally shown as an unsympathetic figure, but someone who nevertheless usually keeps his word.

There are a large number of rapes and decapitations, and sex scenes aren’t avoided. But I read this comprehensive novel with total absorption. In fact, I became obsessed by it over several days. With its many twists and turns of plot, it really does make for outstanding reading.

Lord of Formosa was originally written in English. The author’s own translation of the novel into Dutch (she comes from an Anglo-Dutch background) was discussed, along with another book, in an article in the Taipei Times on Sept. 17, 2016 by Gerrit van der Wees. But Camphor Press last month published this excellent new edition of the English version, and it could hardly be more welcome.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of