March 26 to April 1

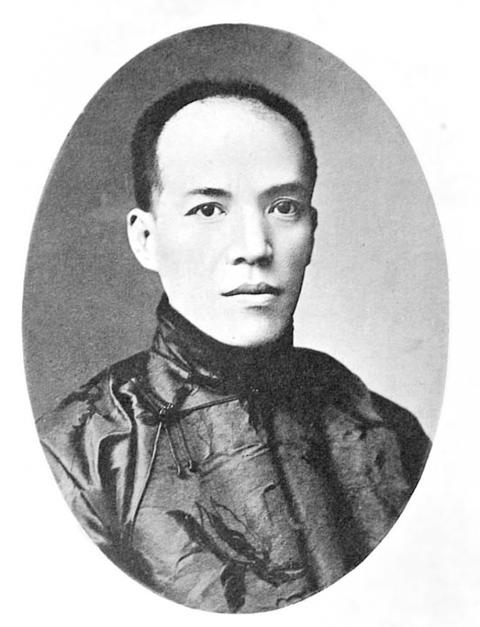

When Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) ran into Liang Qichao (梁啟超) in Japan in 1907, he had a burning question for the influential Chinese scholar and reformist: Where should Taiwan go from here?

A wealthy intellectual from the prominent Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家), Lin would later become a leading figure in Taiwan’s nonviolent anti-Japanese colonialism movement, which aimed to foster Taiwanese nationalism and attain self-rule. But back then, he was a 26-year-old running the family business and serving as local official, living a privileged life but unhappy about his people and country being exploited by foreigners.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Liang, on the other hand, was in exile in Japan after a failed reformist movement in the Qing Empire. Although the two couldn’t understand each other (Lin only spoke Hoklo, also known as Taiwanese), the two had a lively conversation through writing.

Liang told Lin, “China will not have the power to help you in the next 30 years. Why don’t you emulate the Irish and their struggle against the British?”

He warned Lin against armed rebellion, suggesting that the Irish found more success by winning the sympathy and support of British officials and achieving political representation. That’s exactly what Lin would try to do in the future as the main force behind the push for the Imperial Japanese Diet to form a Taiwan representative assembly.

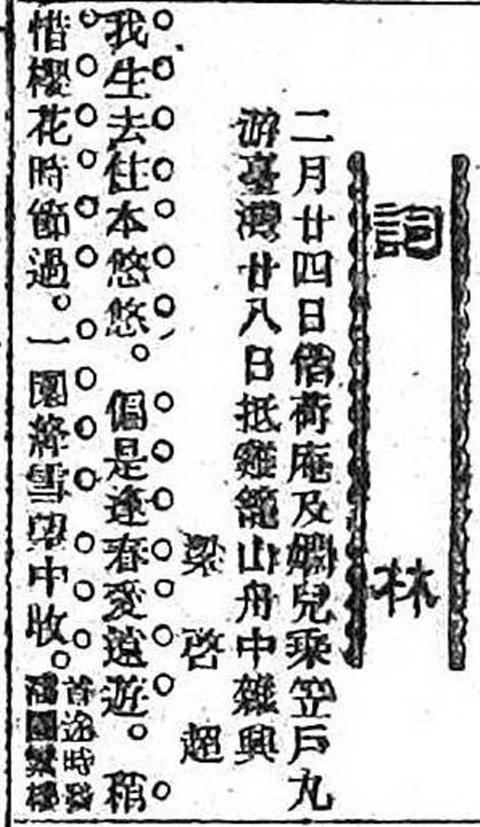

Photo: Chen Chien-chih, Taipei Times

At the end of the talk, Lin invited Liang to visit Taiwan. Liang arrived four years later on March 28, 1911, spending about two weeks in Taipei and Lin’s hometown of Taichung.

OBSERVING JAPANESE RULE

According to the study, Liang Qichao’s Poetry and Writings During His Visit to Taiwan and Taiwan’s National Movement (梁啟超遊台詩文與台灣民族運動) by Chang Pei-yu (張佩瑜), Liang’s primary purpose was to observe the conditions of Japanese rule in Taiwan, but he also immersed himself in Taiwan’s Han Chinese literary circles, leaving behind a significant body of work that expressed his longing for his motherland as well as reflecting the reality of Taiwan under foreign rule.

Photo: Lin Liang-che, Taipei Times

“Even though Liang only stayed in Taiwan for two weeks, his influence is significant,” Chang writes. He not only kickstarted the development of Taiwan’s self-rule movement, he inspired Taiwanese to form cultural organizations to explore new ideas and encouraged people to express their discontent for their current situation through literature.

Lin had long been a fan of Liang’s Xinmin Congbao (新民叢報) publication in Japan that espoused “progressive and modern ideas” with “sharp yet touching prose and compelling discussions.” Chang writes that it was very popular among young Taiwanese intellectuals who felt distaste toward foreign rule and shared Liang’s longing for the “motherland.”

By the time Lin met Liang, Taiwan had already gone through several bloody uprisings that were brutally suppressed. While it was the great losses that compelled Taiwanese to turn to moderate means of resistance, Chang writes that Liang’s words had a great impact on Lin and his actions as a resistance leader.

Photo: Lin Liang-che, Taipei Times

Liang had paid much attention to Taiwan since he was deeply saddened by the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, in which the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan to Japan. In Japan, he would frequently read in local publications how the colonial government had vastly improved Taiwan, which contrasted with what he heard from Lin in 1907.

He was eager to visit Taiwan and assess the situation for himself. Even in exile, Liang was thinking reform. He made a detailed list of items he wanted to observe with the plan of applying his findings to China one day, such as how the colonial government was able to raise Taiwan’s economy in such a short period as well as the effectiveness of its state-run opium business and advanced agricultural technology.

Interestingly, he also wanted to learn about colonial immigration policy and census methods to use as a blueprint for China’s colonization of non-Han Chinese areas such as Xinjiang.

INSPIRING TAIWANESE

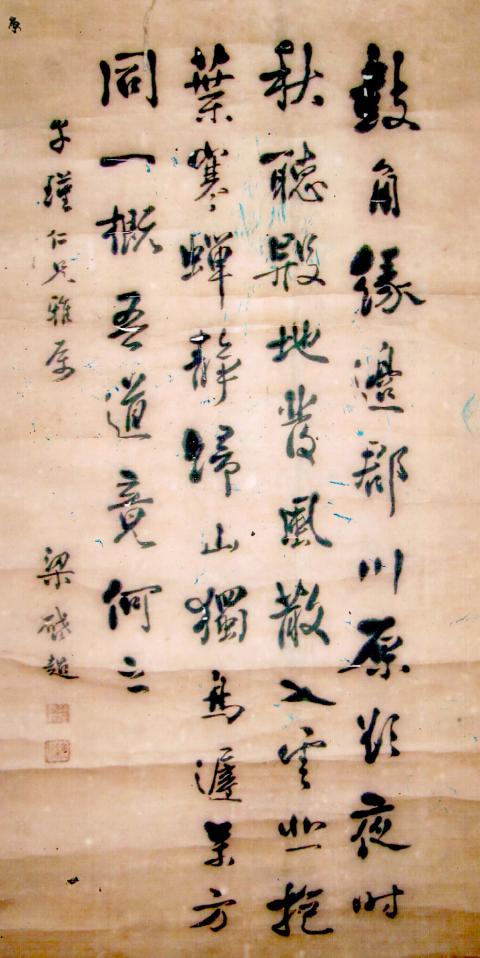

During five days in Taipei, Liang visited numerous government institutions, taking note of the disrespectful way Japanese treated him and other Taiwanese. He wrote several poems mourning the Taipei city walls torn down by the colonizers, comparing the destruction to the plight of Taiwan.

On April 1, under the close watch of the Japanese police, Liang gave a one-hour speech to a crowd of more than 100 local intellectuals who were, as Chang writes, deprived of new concepts and ideas as the Japanese were mostly concerned about teaching their language, while Han Chinese schools focused on Confucian classics. At the end of the speech, he read a new poem to thank the Taiwanese for their hospitality, one of about 80 pieces he would complete during his stay.

In Taichung he spent time with the Oak Tree Poetry Society (櫟社), which was headquartered at Lin’s family garden. The society threw Liang a welcome party with about 30 poets and guests in attendance. While they did not explicitly talk politics due to fear of Japanese surveillance, Liang improvised poems lamenting Taiwan’s situation as well as their collective sorrow of not being able to put their talent to use under a discriminatory government.

Chen Chao-ying (陳昭瑛) writes in Taiwan and Traditional Culture (台灣與傳統文化) that Liang’s visit transformed the spirit of the poetry society: “They shed their sorrow and grief of being an abandoned people, and turned their focus toward cultural enlightenment and nationalist and political activism.”

By the end of the trip, he writes in a letter back home, Liang says he was “very disappointed” in the Japanese. Although he did praise their effective policies and improvements in infrastructure, he noted that this progress came at the expense of the rights of Taiwanese, who were not given any say regarding their own land.

He included three poems in the letter that described concrete examples of Japanese oppression, including one about how the state-run sugar factory had forcefully purchased land from peasants for half the market price.

Finally, he repeatedly warned the Taiwanese elite not to submit to the Japanese in exchange for a comfortable life. He stressed to Lin and his relatives that literature wasn’t enough; that they needed to study politics and economics as well as modern philosophy, giving them a list of 170 books to read before he left.

Lin did not wait for long to act, forming several Taiwanese rights groups over the next few years. After finding no success, in 1921 he heeded Liang’s suggestion and made the first of 15 petitions over the next 14 years to the government to establish a Taiwanese representative assembly.

This was the last straw for governor-general Kenjiro Den, who originally wanted Lin on his side. From then on, Den labeled him as a troublemaker.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she