There was no chance a man surnamed Lin (林) was allowing paramedics into his home. Although a man lay dying in the alley outside his back door, he demanded that they find another way to save his life. Impossible, they insisted, the fire lane is too cluttered with junk to access him with the longspine board, and he needs immediate medical attention.

Lin was adamant.

“There is no way a dying person is coming into my home,” he shouted, according to Chinese-language media accounts in August of last year. “If that happens, my home will become stigmatized. Deal with it yourself.”

Photo: Chang Tsung-chiu, Taipei Times

The injured man, surnamed Lo (羅), later died in the hospital.

Liao Ting-shuen (廖廷軒) of the emergency medical services Phoenix Volunteers (鳳凰志工), who was at the scene, wrote on Facebook that if responders didn’t have to spend an additional 20 minutes accessing Lo, there was a “20 percent to 30 percent” chance that he would have lived. In later interviews, Lin said that he didn’t allow Lo into his home because doing so could have caused its value to plummet by NT$10 million.

Lin’s concerns are justified. At the time, he said that he had no idea if Lo, who fell while installing an air conditioner, was dead or alive. Had he died as paramedics brought him through the house, he feared, it would become a xiongzhai (凶宅), or a home that becomes stigmatized because the ghost of the deceased will haunt it.

Photo: Chang Jui-chen, Taipei Times

“If it were your home, would you have let [Lo] in?” Lin later asked reporters.

The case reveals an all-too-common phenomena: homeowners committing callous acts so as to avoid their house becoming haunted, bearing a direct impact on the housing and insurance market and the mass media. The concern has grown rapidly over the past few years with the notable rise in the number of suicides, demographic shifts that see more people renting apartments and the Chinese-language media’s obsession with reporting on the more gruesome and scandalous aspects of murder and suicide. With xiongzhai, ghosts aren’t causing harm, as the Lin and Lo case shows, people are.

Lin Mao-hsien (林茂賢), an ethnographer of Taiwan’s folk religion and an associate professor at National Taichung University of Education’s Department of Taiwanese Languages and Literature, says Taiwanese believe that people should die in their homes of natural causes such as old age.

Photo: Hsu Sheng-lun, Taipei Times

“If a person dies an unnatural death, particularly a violent one ... their ghost will remain in the place where the person died,” Lin Mao-hsien says.

For Taiwanese, he says, buying a home isn’t only a financial investment, but a familial one — a place where you worship your ancestors and raise your descendants. If a home is occupied by a malicious ghost, ancestors will have no peace — nor will parents and their children.

The ghosts of suicides and murders are particularly menacing: the more gruesome the death, the more malevolent the ghost, the more the price of the home will plummet. Rooming with these ghosts, it is believed, will result in financial failure, health problems and death.

Photo: Wang Ting-chuan, Taipei Times

Indeed, the fear of inhabiting these homes is so great that the owner is legally obligated to tell any prospective buyer that an unnatural death has occurred within its walls, virtually guaranteeing that its value will plummet — if it can be sold at all.

Lin Mao-hsien says the only way to rid a xiongzhai of a malevolent spirit is to tear it down.

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

Photo: Ting Wei-chieh, Taipei Times

When a news anchor surnamed Shih (史) committed suicide by asphyxiation in his rented apartment in 2014, the owner, surnamed Wang (王), sued the newsman’s wife and parents for NT$6 million.

Wang claimed that Shih should have known that his suicide would result in the unit’s market value to plummet, and that he should have taken his life elsewhere. Wang lost the case in March 2016, when a Taipei District Court judge ruled that Shih’s parents and wife were not liable because he had a documented history of depression.

Wang has appealed the ruling to the High Court, which is still reviewing the case.

Photo: Liu Chih, Taipei Times

Had the death occurred before 2008, Wang could have kept the suicide to himself and sold the apartment at market value (though the death was covered extensively by the media). But in July of that year, the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) amended housing contracts to include the question: Has an unnatural death occurred in the home for sale?

Lisa Yeh (葉凱禎), a lawyer, writes in the article, “How to legally define xiongzhai,” (怎麼定義法律上認定的凶宅?) that the MOI defines murder and suicide as unnatural deaths, which means that even if Lo had died passing through Lin’s home, he wouldn’t be legally obligated to state it to any prospective buyers.

The MOI’s additional wording places the burden of responsibility on the homeowner. Failure to inform prospective buyers that an unnatural death has occurred in the property for sale can lead to a fine, the seller having to take back the property and compensate the buyer, or both. If the seller intentionally deceives the buyer, they might even go to jail.

Photo: Yu Tai-lung, Taipei Times

In a 2009 case, Lee Chiong-chi (李炯祺) was sentenced to eight months in prison after Chang Teng-yu (張?煜) proved that Lee deceptively sold him a xiongzhai in New Taipei City’s Luzhou District (蘆洲), according to a report in The Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper).

Yeh says that although the law is clear, buyers should always do their due diligence to ensure that the home they are about to purchase isn’t a xiongzhai.

“The consumer can avoid hassles,” she writes, “by talking to those who know the community where the home is located — neighbors, police and real estate agents.”

Photo: Huang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

But herein lies a problem. It only takes one neighbor to describe a death as “unnatural” to convince a prospective buyer that they do not want to be associated with a property’s perceived association with the pollution of death.

Some people are so concerned that they will insist that paramedics perform emergency treatment away from their homes, as happened in December, when a 68-year old Taitung man shooed away paramedics, saying “don’t give emergency medical treatment on my doorstep,” according to the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper).

The person he was referring to had just suffered a heart attack.

And it’s not only homeowners who are concerned with malevolent ghosts. Although sellers are obligated to state whether or not an “unnatural death” has occurred in the home they are listing, landlords are not held to the same standard.

A 27-year old woman surnamed Lin (林) moved with her dog into an apartment in New Taipei City. Over the course of the following few days, she claimed that her normally quiet dog would not stop barking. Concerned, she spoke to her neighbors who told her that a man had recently committed suicide in the apartment. Angered, Lin sued the landlord, but the prosecutor refused to hear the case because, according to the law, the landlord isn’t obligated to inform prospective renters that an unnatural death has occurred.

SUICIDE WATCH

Perhaps the biggest reason behind the growing number of xiongzhai is the nation’s high rate of suicide, which, according to Ministry of Health and Welfare statistics, had steadily increased since the 1990s until it reached a peak of 19.3 deaths per 100,000 in 2006 — two years before the MOI amended housing contracts, and much higher than the global average that year of 16.8 per 100,000. The statistics also showed that there were 16 deaths per 100,000 last year, again beating out the global average of 12.3 per 100,000.

A closer look at the demographics paints an even grimmer picture. Within Lo’s age bracket — 25 to 44 years old — there were 22 deaths per 100,000 last year, up from previous years, but still less than the 35.3 per 100,000 in 2006. For males 65 and older, the number of deaths jumps to 46.2 per 100,000 last year, though down from 51.1 per 100,000 in 2006.

In addition to the high suicide rate is how the media sensationalizes them, publishing photos of the deceased and including graphics that depict the manner in which the person took their life and the location where the death took place — all under the idea that a family’s privacy takes a back seat to the public’s right to know where xiongzhai are located.

Many of the posts on Web sites devoted to xiongzhai offer links to articles published by Apple Daily’s xiongzhaidaka (凶宅打卡, “Xiongzhai Check-in”), a column that offers in-depth profiles of famous and infamous xiongzhai cases dating back decades.

In its 2014 inaugural column, it wrote about the 2006 murder of five children in Hualien, when Liu Chih-chun (劉志勤) and his wife Lin Chen-mi (林真米) allegedly bound with wire the hands and feet of their five children, aged eight to 18, and strangled them to death. The bodies were found stacked in the second floor bathroom of their townhouse. The remains of the couple were found years later by an Amis hunter on Tzuyun Mountain (慈雲山).

The townhouse was immediately labeled a xiongzhai and the community where the murders occurred was so concerned about the malevolence of the ghosts, the police officer in charge of the case, Keng Chi-wen (耿繼文), slept in the house for a week as a means to show that there was nothing to fear.

It didn’t work.

Unluckyhouse.com, the oldest and most comprehensive Web site that tracks the nation’s xiongzhai, enables members to post where they are located and the news items on which the address is based.

There is also a xiongzhai map (凶宅地圖) on Google showing many of them in Taipei that resulted from suicide.

Shih’s suicide was covered extensively by the Chinese-language media, so it isn’t too much of a stretch for Lin to fear that Lo’s fall wasn’t accidental.

The incessant reporting of suicide and murder has another consequence: discriminatory rental practices.

Ads for rental properties generally target female office workers due to the accurate belief that men are more inclined to commit suicide than women (double according to MOHW statistics), and the suicide rate for those over 65 is consistently over 30 per 100,000 (the global average is 10).

And many don’t want to rent out their property at all, a problem in a place like Taipei with high housing prices and a dearth of affordable housing.

The Taipei City Government recently announced that there are more than 35,000 homes that have been vacant for more than a year.

Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) said at a news conference in November last year that the city would offer tax breaks for any landlord willing to rent out an apartment. But even Ko seemed doubtful at the press conference.

“Many landlords are not willing to let out empty units for rent because they are afraid of trouble,” Ko says.

PROTECTING YOURSELF

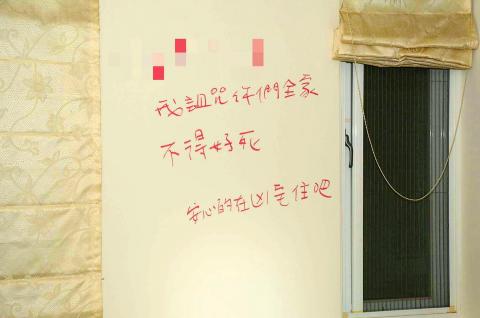

In September, a woman surnamed Tsai (蔡) committed suicide by hanging in the Chiayi townhouse of her boyfriend’s ex-wife. On the wall Tsai scribbled: “I curse your family to a bad death. Hope you enjoy living in a xiongzhai.”

Liu Wei-te (劉韋德), head of the legal department at Sinyi Realty (信義房屋), Taiwan’s largest real estate company, tells the Taipei Times that Taiwanese will not only have a strong resistance to xiongzhai, but also the apartments next to it, the building it is housed in and, depending on the degree of a person’s fear of ghosts, the complex where the building is located.

In 2011, the company unveiled its “xiongzhai peace of mind guarantee” (凶宅安心保障服務), an assurance that the company will not knowingly sell a xiongzhai.

“When a customer buys a xiongzhai, there is absolutely nothing you can do to console them,” says Jeremy Shive (薛健平), Sinyi’s general manager.

Liu says Sinyi’s market research showed that “94 percent of Taiwanese have a moderate to strong aversion to living in a xiongzhai.”

“If a buyer has a strong resistance to buying a property in a complex that has a xiongzhai, then there is a good chance they won’t find a place to live [in Taipei],” Liu says.

Liu estimates that there are 150,000 of these properties throughout Taiwan.

Liu adds that the market price of a xiongzhai varies according to the nature of the person’s unnatural death. The more violent the death, the more the house plummets in value.

“A suicide by jumping from the 10th floor will not have as much an impact as a murder on the 10th floor,” he says.

Liu cites the murders in Hualien as an example.

“It was a horrific murder. Nobody would dare live there for years,” Liu says.

Lin Mao-hsien disagrees that the degree of fear associated with unnatural death impacts the value of a property. For him, a xiongzhai is a xiongzhai is a xiongzhai, and it is the responsibility of the owner to tear it down, regardless whether a grisly murder, accidental death or drug overdose occurred within its walls.

He cites a partially-constructed building in Chiayi where a man hung himself that would have to be torn down and rebuilt to ensure that the ghost wouldn’t negatively impact the new inhabitants. Lin Mao-hsien says that even a tree can suffer this kind of haunting if, for example, a person commits suicide by hanging from it.

The growing number of suicides and murders, and the media’s incessant reporting on them, led Fubon Insurance (富邦人壽) to introduce a xiongzhai insurance policy — one that is similar to earthquake or flood insurance.

Fubon’s Ingrid Lin (林晨) tells the Taipei Times that the company’s market research estimates that 2,000 homes become xiongzhai every year.

“Few can seek compensation,” Ingrid Lin says. “When a house becomes a xiongzhai it loses at least 30 percent of its value. The homeowner is unable to be compensated for this loss, and consequently must sell the home at a significantly reduced price.”

Since it introduced the commodity in 2016, the insurer has sold over 11,000 policies.

And they can only expect to sell more as Taiwan’s suicide rate remains high and property owners refuse to help out.

“Taiwanese believed in xiongzhai 30 to 40 years ago, and they will believe in xiongzhai 30 or 40 years into the future,” Liu says.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had