JAN. 29 to Feb. 4

Frederick Coyett languished for nearly a decade on the remote island of Pulau Ai in the eastern part of present-day Indonesia.

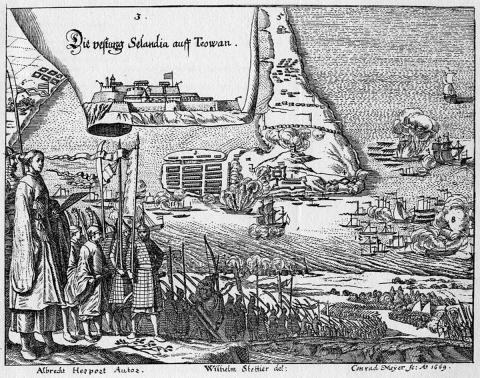

Born into Swedish nobility, Coyett’s glory days came to an end when, as governor of Dutch-ruled Formosa, he surrendered the colony to Ming Dynasty loyalist Cheng Cheng-kung’s (鄭成功, or Koxinga) forces on Feb. 1, 1662.

Photo: Ting Wei-chieh, Taipei Times.

Koxinga spared Coyett’s life, but the irate Dutch sentenced him to death for the mishap. He was later pardoned and exiled to Pulau Ai in 1666. From there, he began writing his account of the events, Neglected Formosa, in which his intentions are made clear in the very first sentence: “[This book is] about the intentions and preparations of the Chinese to invade the island of Formosa, and the careless and inefficient precautions taken by the Dutch authorities to defend that possession.”

According to the book’s preface, Neglected Formosa was only available in Dutch and German for more than 250 years until a Japanese version appeared in 1939. Scottish missionary William Campbell translated portions of the book and incorporated them into his 1903 work Formosa Under the Dutch, but a complete translation to English was not completed until 1975. The first Chinese translation was published in the 1950s.

“This is a book of vindication by the man who was made to bear the blame for the loss of Formosa by the Dutch in 1662,” writes anthropologist Inez de Beauclair in the introduction to the 1975 edition.

Photo: CNA

WARNINGS UNHEEDED

Born in Stockholm, Coyett joined the Dutch East India Company in his early 30s and made his way to Taiwan as vice-governor of the Dutch colony based in present-day Tainan. He is said to be the first Swede to visit Japan and Taiwan.

Coyett was promoted to governor in 1657. After his banishment, it was only through the intervention of his relatives that he regained his freedom in 1674, returning to Europe in 1675. Since Neglected Formosa was published in Amsterdam right before he arrived, it’s safe to assume that he wrote it during exile.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The first portion recounts Koxinga and his father’s anti-Qing activities and also provides an overview of life in Taiwan and Dutch colonial activities. Coyett first describes Koxinga as “no less brave than his courageous father … nourishing the same implacable hatred toward the [Manchu rulers of China].”

In 1652, a Jesuit priest warned the Dutch that Koxinga had his eye on Formosa and was planning to incite the Han Chinese inhabitants to revolt against the colonizers. An anti-Dutch uprising led by Kuo Huai-yi (郭懷一) took place, and the company instructed the governor to “keep an eye on Koxinga.”

Coyett writes that in the ensuing years he would send periodical warnings to company headquarters, but a rival managed to convince company officials that Coyett’s “fear for a war was only imaginary and was caused by [his] cowardice.”

In 1653, the Dutch built Fort Provintia in response to the rebellion, but Coyett criticizes it as “too feebly built” — capable of dealing with uprisings but unable to withstand a siege or hold out against cannon fire.

As governor, Coyett tried to make peace with Koxinga, sending him and his commanders presents and heeding Koxinga’s request to reopen trade between China and Taiwan. At the same time, he requested that the Dutch East India Company repair several dilapidated fortresses and build several more — but no help came as his superiors claimed financial difficulties.

As Koxinga’s forces lost ground to the Qing Empire, the Dutch authorities in Taiwan were convinced that he would invade in the spring of 1660. He never arrived, reportedly because he had gained some ground against the Qing and that he also heard of Coyett’s preparations to defend Taiwan.

While the company acknowledged the threat and praised Coyett for his actions, Coyett writes that they still seemed unconvinced.

“We cannot entirely believe that said Koxinga will wage a war against the Company (unless as a last resort), as he is fully aware of how such would be to his disadvantage,” an official wrote to Coyett in April 1660.

Coyett cites this attitude by his superiors as one of two main reasons for the loss of Taiwan. The second was their refusal to spend any money to bolster the colony’s defenses, promptly shooting down all of his proposals. They were even angry that Coyett had bolstered Fort Zeelandia’s weak east wall on his own accord.

“The officials in Formosa had sufficiently shown themselves very active in everything that could advance the interests of the Company,” Coyett writes. “Why, then, complain, and instead of animating them in these troubles and in their zeal to safeguard the affairs of the Company, why object, and reprove them with disheartening words by rejecting their useful proposals?”

FORMOSA LOST

Koxinga finally took action in April 1661, one year past the expected attack. In less than two hours, a considerable portion of the fleet had entered the colony’s bays with a few thousand soldiers reaching land.

His forces pushed forward and soon laid siege to Fort Zeelandia. The company finally sent a fleet to help out, but Coyett writes that nobody wanted to assume command of the fleet until an adventurer, Jacob Caeuw, who had no military experience, signed on for the job. Caeuw was of little help and eventually excused himself back to headquarters.

“‘Formosa is lost,’ was the general cry amongst all Indian nations and the administrators in Holland,” Coyett writes. “The governor and council of Formosa were regarded as first-class delinquents, but these, not willing to lose their character and honor by admitting themselves to the blame for the loss of Formosa, openly declared that they had been too much tied down; that the assistance sent was not sufficient; and, in short, Formosa had been neglected [by the company].”

The company was so displeased with Coyett that they sent a replacement governor, but this man saw the situation and never landed, finally fleeing for Japan. Unable to hold out much longer, Coyett signed an instrument of surrender with Koxinga.

Coyett would have spent the rest of his life in Pulau Ay if not for his friends and children, who petitioned Prince William III of Orange for his release. The conditions were that he settle in the Netherlands and never take part in any “Eastern affairs” again. His family also had to pay 25,000 guilders.

In 2006, Coyett’s 14th-generation descendant Michael Coyet (different spelling) and his family visited Taiwan from Belgium. They visited the Koxinga Shrine in Tainan and paid tribute to him for sparing their ancestor’s life.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of