Dec. 25 to Dec. 31

In December 1987, desperate criminals made a last ditch effort to win the Patriotic Lottery (愛國獎券) by kidnapping the teenaged son of the lottery’s director, asking for the winning numbers for ransom.

The situation was resolved without incident. On Dec. 27, the very last Patriotic Lottery tickets were issued for public purchase. The next day, nearly a thousand Patriotic Lottery vendors staged a protest in front of the Executive Yuan, asking the government to reverse its decision to stop issuing the tickets to no avail.

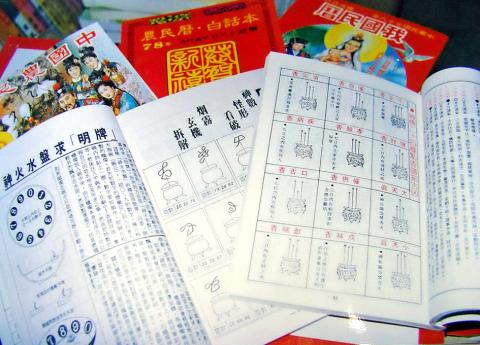

Photo: Lu Kuan-cheng, Taipei TImes

The government-run operation lasted 37 years and sold more than NT$68 billion worth of tickets, with about half of it going to the National Treasury. The real culprit was not the lottery itself, but the dajiale (大家樂, literally “happiness for everyone”) gambling rings that bet on the Patriotic Lottery winning numbers. This became a huge craze that reportedly caused a plethora of societal problems and conflicts.

GET RICH QUICK

Liu Wei-ching (劉葦卿) writes in the book, Taiwanese Dreams of Becoming Rich (台灣人的發財美夢), many common sayings back in the day involved the Patriotic Lottery, including “This is harder than winning the Patriotic Lottery” and “When I win the Patriotic Lottery, I will do such and such.”

Photo courtesy of WIkimedia Commons

Taiwan’s first government-run lottery program was established in 1906 under Japanese rule, with the money used to fund programs such as public sanitation and temple restorations. The initiative was scrapped in just seven months. The Japanese had hoped to use the lottery system to curb the Taiwanese habit of gambling, but it actually made matters worse as people started abusing the system to swindle others.

Facing massive military costs and inflation in the early years of its rule, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) launched the Patriotic Lottery program in April 1950. Liu writes that the government was needed the money so badly that they started selling the tickets on April 11 despite the Executive Yuan not officially approving it until April 22. Slogans appeared in the newspapers such as “By being patriotic, you have a chance to become rich.”

The tickets went through many price adjustments over the years as well as system changes. Sometimes the government would raise the prices before the Lunar New Year as that was when people had just received their annual bonuses. Tickets were typically issued three times a month until dajiale forced the government to cut back. In the beginning, the top prize was about 140 times an average person’s annual salary, but as Taiwan’s economy improved, by 1987 it was only six times. Over the years, special lottery tickets were issued to fund specific projects such as the rebuilding after the devastating 1959 flood.

Taipei Times File Photo

Another interesting scheme took place in 1973 during a nationwide NT$1 coin shortage, and children were encouraged to pay NT$100 tickets all in coins for a chance to win a color television.

Intricately designed with illustrations of scenery, animals, folk stories, propaganda, current events and so on, the ticket graphics often reflect the climate of Taiwanese society at the time of issue. The 1950s focused on defeating the Communists and retaking China while the 1960s were dedicated to propagating Chinese culture. The 1970s focused on Confucianism and morality, often featuring historic tales about virtuous figures. In the last few years, the tickets often featured new infrastructure projects such as the Third Nuclear Power Plant.

Ticket designer Lin Hsing-hsiung (林幸雄) was even kidnapped three times by people who tried to force the winning numbers out of him — and of course he had no idea.

The Patriotic Lottery was long an integral part of society, appearing in pop songs, movies, novels and other endeavors. They are now collectors’ items today, often appearing on eBay and other auction Web sites.

THE GAMBLING ISSUE

Around 1985, the dajiale craze took over Taiwan as vendors devised a new game where people would bet on the last two numbers of the eighth prize for the Patriotic Lottery. The “banker” would take 10 percent of the profits while the rest were distributed among the winners. This actually become more popular than the Patriotic Lottery because the odds of winning were higher and the payout was divided among fewer people.

Many turned to religion, praying for the gods to reveal the winning numbers. Liu writes that in addition to asking spirit mediums, they would observe smoke patterns from burning incense and visit graveyards at night hoping for a revelation. This led to an odd situation where people defaced and discarded numerous statues of deities that failed to help them win, giving rise to the phrase luonan shenming (落難神明, or gods fallen on hard times). Others claimed to know the winning numbers and would place ads in the newspapers to sell them.

Liu writes that at the height of the craze, an estimated 20 percent of Taiwan’s population was involved, while other figures go as high as 39 percent. Chiu Hei-yuan (翟海源) writes in A Study of the Dajiale Phenomenon and its Effects (大家樂現象之成因與影響之研究) that by 1987, the phenomenon covered 88 percent of Taiwan’s districts, towns and townships in operations that required between NT$10 billion and NT$50 billion per month.

Some got rich quickly, but many lost everything. Liu writes that there were also positives. In a time where there was not much public entertainment, dajiale became a social activity that brought people together. It also played a part in preserving traditional performance arts as people would invite troupes to perform and thank the gods after winning big.

Police frequently busted dajiale operations, with more than 6,000 cases between July 1986 and June 1987. But they would simply move locations and hide behind other business such as betel nut stands and hair salons. The nation’s banks even faced cash shortages on days Patriotic Lottery numbers were revealed due to people withdrawing their money to participate in dajiale. News reports stated that that people stopped going to work, farmers stopped planting and markets closed. All walks of life were involved, from teachers to politicians to gangsters.

The government tried to raise the winning odds for the lottery and made other modifications, but people were not deterred. In July 1987, a man robbed a bank in Hsinchu, later claiming that he did it because he lost his savings to dajiale. However, a majority of the interviewees in A Report on the Formation of Dajiale Problem and How to Stop it (大家樂問題成因及防治途徑專案研究報告) claim that the habit has not affected their personal lives and that the media and government were exaggerating.

A month later, Premier Yu Kuo-hua (俞國華) cited dajiale among the “various abnormal phenomena in society,” comparing it to teenage motorcycle gangs. The Executive Yuan commissioned a team of academics to look into the issue and come up with solutions to the problem.

Most recommended against terminating the Patriotic Lottery program as a solution, citing that it may cause further confusion and that people will always find new ways to gamble. But in the end, the government still cut the program.

The academics were right, as people simply switched over to using the winning numbers of Hong Kong’s Mark Six lottery.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the