Dec. 11 to Dec. 17

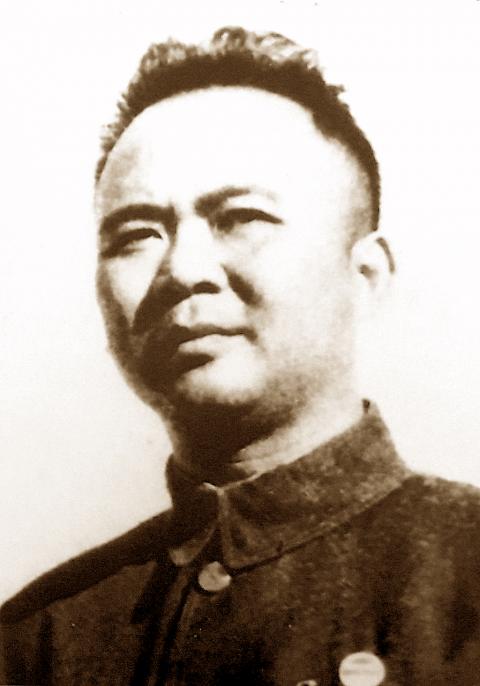

Lee You-pang (李友邦) thought his struggle was over when he returned to Taiwan in mid-December of 1945. After all, he had achieved his dream of helping free Taiwan from the grasp of the Japanese Empire and returning it to the “motherland” of China.

But more trouble lurked under the rule of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), which assumed control of Taiwan when the Japan surrendered at the end of World War II. Three months after Lee’s return, governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) disbanded Lee’s Taiwan Militia (台灣義勇隊) without discharge orders or pension, essentially hanging out to dry the group of men and women who had spent six years helping the Chinese fight the Japanese.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lee was later jailed on charges of corroboration with the “communist bandits” and inciting rebellion during the 1947 anti-government uprising and subsequent brutal crackdown that would be known as the 228 Incident. His wife and comrade-in-arms, Yen Hsiu-feng (嚴秀峰), saved him that time, but she was in jail when he was taken away again in 1951 on charges of colluding with the Chinese Communists Party (CCP) to overthrow the government.

On April 22, 1952, Lee was executed by the regime he had hoped to support. He was 46. Yen was released from jail in 1965 and spent the next 50 years raising five children, trying to clear her husband’s name and preserving the historic Lee home in New Taipei City’s Lujhou District (蘆洲), which is today open to the public.

“Lee You-pang should have died on the battlefield,” Yen is known to often have said. “Instead, he died in his beloved homeland for which he gave his all.”

Photo: Wu Chia-yi, Taipei Times

But she adds that she would not hesitate to do it all over again.

ETERNAL REBEL

Lee was a wanted man by the time he was 18 years old, having led student attacks on Japanese police stations in 1922 and 1924. Anti-Japanese sentiment among students was high during that period, especially with the 1921 establishment of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), which aimed to passively counter Japanese rule by fostering an awareness of Taiwanese nationalism.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Narrowly dodging arrest, Lee fled to China where he enrolled in the the newly-established Whampoa Military Academy (黃埔軍校) and joined the KMT. During this time he formed the Taiwan Independence Revolutionary Party (臺灣獨立革命黨) — but under this context he meant independence from Japan so Taiwan could return to Chinese rule.

He spent the next few years organizing anti-Japanese activities among Taiwanese living in China, and eventually spent time in Tokyo under the guise of a Waseda University student, networking with local revolutionaries.

Lee’s group was disbanded during new KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) communist purge in 1927 as it was deemed to have leftist leanings. Having nobody else to turn to and with the Japanese on his tail, Lee joined the Communist Youth League of China (中國共產主義青年團) and started teaching Japanese in Hangzhou.

Photo: CNA

In 1932, he was arrested by the KMT and subjected to heavy torture. By the time he was released in 1934, both his younger brothers, also revolutionaries, were killed by the Japanese.

The Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, upon which Lee immediately revived his party. In 1938, he formed the Taiwan Militia with the help of the Communists and the approval of the KMT, who were working together against a common enemy.

The following is an excerpt from Lee’s recruitment speech: “Now our great motherland has raised the banner and is resisting the Japanese. This sacred battle has been going on for more than a year now, and this is the perfect chance for us Taiwanese to liberate ourselves. My dear compatriots, how can we continue to watch from the sidelines? How can we bypass this chance to fight with the motherland to defeat our hated enemy for the past 40 years?”

NO PLACE FOR LOVE IN WAR

Around the same time, a 17-year-old Yen left Hangzhou for the battlefield. The only child of a well-to-do family, she begged her father relentlessly for five months before he let her go to war. She showed her bravery with a daring run across the frontlines to deliver secret documents to another camp, spending the last two hours crawling through bushes in the mountains.

Lee and Yen met on the frontlines, and they started spending time together as he offered her Japanese lessons. She turned him down when he proposed, telling him there’s no place for love in war. But Lee was persistent. The pair married in 1941, and she started working for the Taiwan Militia.

The militia’s main tasks were medical support, propaganda and production, but it also saw action, including several raids into Japanese-ruled Xiamen, where they snuck in and put up anti-Japanese posters. It also made use of its members’ knowledge of Japanese to carry out various rescue and reconnaissance missions.

Lee welcomed Taiwanese of all walks of life into his group, including many Communists. This drew the attention of the KMT, which Yen says sealed his fate.

Back in Taiwan, Lee ran the Taiwan branch of the Three Principles Youth Group (三民主義青年團), while Yen helped out and offered Mandarin lessons. When the 228 Incident broke out, Chen asked Lee to broadcast a plea for the people to stop resisting, but Lee refused and criticized Chen for corruption and misrule. Soon, he was arrested and sent to Nanjing.

A pregnant Yen traveled to Nanjing and somehow managed to get an audience with Chiang Kai-shek’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), who suspected that Lee incited the uprising. Lee was eventually let go and returned to Taiwan to great fanfare.

In 1950, Yen was sentenced to 15 years in jail for meeting a suspected Communist. This time she was unable to save Lee.

EPILOGUE

It was around dusk on Aug. 15, 1945 when Lee and Yen heard the news. A local reporter had run into his house, yelling: “They’ve surrendered!”

Lee and Yen couldn’t believe it. “Who announced it?” they asked.

“We received word from the Americans,” the reporter said.

They jumped up at the same time and hugged each other, fighting back tears. “We’ve won,” Lee shouted as they left their dinner unfinished and ran outside to spread the word.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On