Nov. 06 to Nov. 12

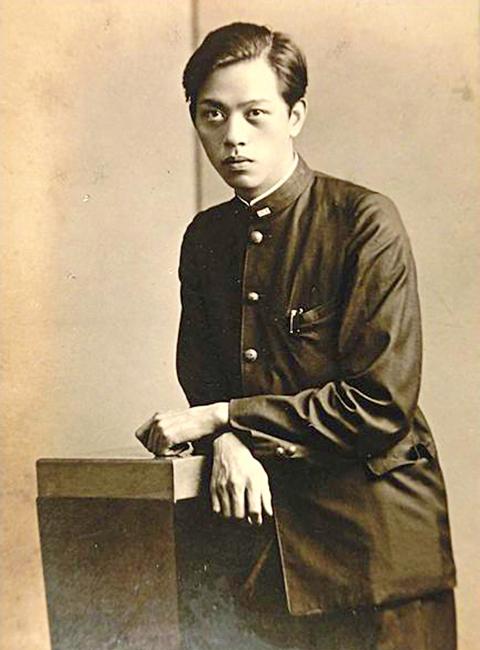

Su Beng (史明) snuck into Taiwan from Japan in October 1993, the last leg via fishing boat from Yonaguni island. He climbed ashore to a familiar sight in the dead of night — 44 years previously, he had landed not too far from this the exact same spot after his flight from China, also during the wee hours.

Su was soon picked up by the police and taken to Taipei to stand trial for illegal entry among other charges. Defiant as ever, he proclaimed, “I did not come back to visit my relatives. I came back to overthrow the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) colonial rule and to fight for Taiwan’s independence.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It might have been an audacious thing to say in his day, but this was no longer the Martial Law era, and the long-time blacklisted activist managed to avoid jail time. After having spent only three years of his adult life in Taiwan, Su was home for good.

PREPARING THE COMEBACK

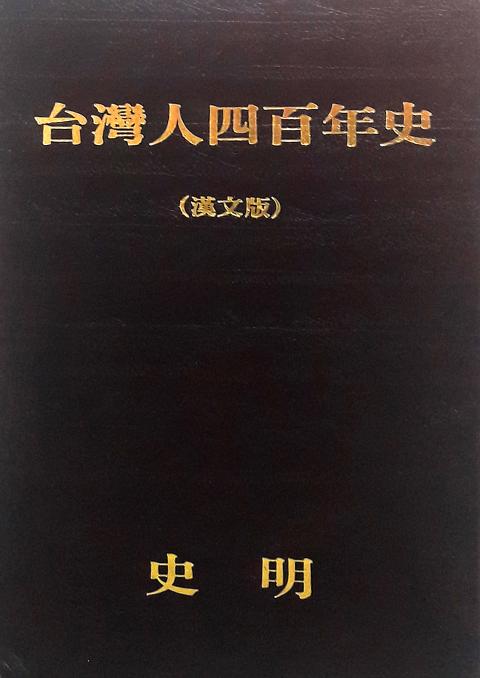

Su had been living in Japan since 1952, when he fled Taiwan after his plan to assassinate former KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) was leaked. He remained active in independence activities, and is best known for publishing the book Taiwan’s 400-Year History (台灣人四百年史) in 1962. Written in Japanese, it was translated in to Chinese in 1980 and English in 1986.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

As Taiwan showed signs of democratization in the 1980s, Su contemplated returning home to continue his fight on the frontlines.

“All signs pointed to the weakening of the KMT’s grip over Taiwanese society,” he writes in his autobiography. “The people have also started developing a Taiwanese consciousness. Thus, I was very optimistic about the political future of Taiwan.”

Su had set aside a substantial amount of money earned through his restaurant in Tokyo, and also began training future activists. These ordinary citizens would travel to Japan on the pretext of tourism but would actually spend seven to 10 days with Su, learning about activism and Taiwanese history. Su writes that he hosted groups as large as 30 people.

Photo: Liu Hsin-te, Taipei Times

His plans were put on hold when five of these trainees were arrested in May 1991 and charged with sedition in what would be known as the Taiwan Independent Association incident (獨台會案). However, public outcry led to the repealing of the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) and the amending of the Criminal Code to only punish those who used or planned to use violent and forceful means to commit sedition. Since the defendants only published and disseminated material about Taiwanese independence, they were acquitted.

When another group of his trainees founded a pro-independence association in Kaohsiung’s Fengshan District (鳳山), Su could not wait any longer. Once home, however, he realized that times had changed and the armed resistance that he had formerly engaged in would not work in a gradually liberalizing Taiwan.

“I knew that Taiwan did not have room for armed resistance,” he writes. “After all, most people are afraid of such activities due to the false ‘democracy’ provided by the enemy. So I turned my focus to mentoring and organizing.”

On a side note, one of the things that surprised Su after his return was the proliferation of beef noodle shops.

“Taiwanese did not eat beef during the Japanese era,” he writes.

WORKING FOR THE COMMUNISTS

In 1942, Su was unhappy with his task as a secret agent for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Japanese-occupied Shanghai and Suzhou.

“I came to China to join the resistance. Why am I still interacting and dealing with the Japanese? Perhaps it’s because I looked Japanese, I could enter Japanese military institutions with ease. My job was not even dangerous.”

Born on Nov. 9, 1918, Su first left Taiwan in 1937 to study political economics in Tokyo. During this time, he voraciously read books on anarchism and socialism, and was especially drawn to Marxism, which was his main inspiration for heading to China to fight the Japanese.

“First of all, through Marxism I took notice of the CCP and started learning about China. I felt that China was a place where socialism could prevail,” he writes. “Secondly, China had became the main battlefield for resisting the Japanese Empire. I believed that in order to rid Taiwan of Japanese imperialism, the best way was to start from China.”

Su remained in the Japanese-held areas until the end of the war. He says that he initially had a good impression of Communist leader Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

“But that all changed when I entered the Communist-ruled areas,” he writes, as he moved to Zhangjiakou in Hebei Province in 1946. Over the year, he became disillusioned with the CCP, noting that they had no intent of liberating the oppressed and were instead creating a system of fear and terror. Later he completely gave up on them after seeing the brutality of the class struggle.

Su finally saw combat, engaging in guerilla warfare with the KMT. He also oversaw a division of Taiwanese troops who were initially sent to China during the Chinese Civil War by the KMT but captured by the CCP. The poor treatment of these soldiers made Su realize that “the Communists never saw Taiwanese as one of their own,” which only strengthened his identity and desire to leave China.

As China fell to the CCP in 1949, Su fled back home only to find that the KMT’s behavior was no better than that of the CCP.

“Turns out, both Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong believe in authoritarianism,” he writes.

For Su, there was only one final path to take.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual