Indian cuisine has struggled to find its place in Taiwan’s international food scene. Not rare enough to be cast among the “exotic” types that have but a handful of representative restaurants in Taipei (think Peruvian, Russian or even Turkish), nor popular enough to join the mainstream giants (Italian, Thai, Korean), it occupies a culinary no man’s land where most restaurants stick to the predictable Taj Mahal formula to get noticed.

My passion for the condiments of the subcontinent began back in college, cooking with my Indian roommate. Years spent bonding over the rituals of onion chopping and roti tossing, we not only forged a lasting friendship, but also fine-honed a string of curries that have been the talk of countless dinner parties I’ve hosted since. I’m the kind of person who has a list of favorite Indian restaurants, and I’m always looking to add to it.

And so it was with high hopes that my wife and I came to Saathiya (莎堤亞), located on a second floor on Xinyi Road (信義路), just above Dongmen MRT Station (東門). You’d miss it if it weren’t for the orange, green and white menu stand at the bottom of the stairwell. Nothing, (except perhaps the Taj Mahal), says Indian restaurant quite like the country’s trademark tricolor.

.jpg)

Photo: Liam Gibson

We sit by a large window at the far end of the space which overlooks Xinyi Road. Its low-key for a Saturday night. The place is almost empty except for a couple of tables. The walls of the place are lined with abstract paintings of a remarkably consistent style, courtesy of the owner’s friend and long-term Taiwan resident, artist Sagar Telekar. The paintings are aesthetically pleasing, but stand in jarring contrast next to the flat-screen monitor playing an MTV-like stream of Bollywood dance scenes. The seats are Ikea-chic: simple, black and covered with a nice padding that upon second squeeze feels like one of those thick, cushy mouse pads that gamers use.

We are served by a young Mongolian waiter/waitress duo. Neither can speak Chinese, (nor Hindi for that matter), “Only English,” they say. My wife lets me order.

Flavoring a curry’s gravy with methi (fenugreek seed powder) takes experience. Believed to have special medicinal properties, it’s something of an acquired taste, even in India. I’ve ruined plenty of curries crossing the threshold where stimulating acidic bite becomes bittery awfulness. Saathiya’s methi malai paneer (NT$350) past the test. The methi flavor is subtle, but noticeable, just as it should be.

Photo: Liam Gibson

A plain lassi (NT$100) is a must if you’re sampling multiple curries in one sitting. Its tangy/salty sharpness helps bring your palate back to ground zero in a quick neutralizing gulp. This one delivered the palate-purging hit and a satisfying mouthful of yoghurt-milky frothy goodness.

The aloo paratha (NT$125) was a major disappointment. Undercooked, damp, oily and served on ugly pieces of paper towel.

One critical test for any restaurant, but especially so for Indian ones, is whether or not they can tailor the spice level to your specifications. Saathiya needs to work on this. I asked for the Hyderabadi special chicken curry (NT$380) to be very spicy and it was medium, at best. If they can’t get it right using their preferred English, I can’t imagine how they’d fare in Mandarin.

Photo: Liam Gibson

The spinach-based gravy of the palak paneer (NT$320) was smooth, thick and just a little pulpy. Unfortunately, that was all this dish got right. The paneer was sliced into cubic pieces, chewy but bland. Lightly frying paneer with jeera (cumin seeds) really transforms its flavor. But it seems they’d rather skimp on the seeds here, and so its aromatic potential was left unrealized. Inch-sized onion slices were an unpleasant surprise. This faux pas would have been permissible if it were accompanied by other veggies such as bell peppers, (as is usual in dishes like paneer tikka masala), but as it was the only vegetable in the gravy, it was hard to overlook.

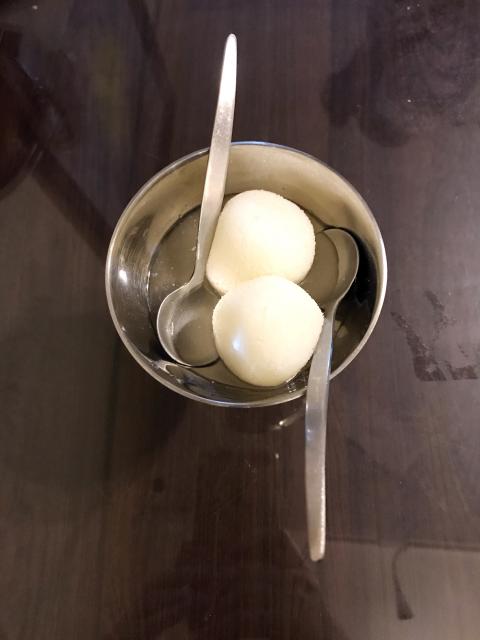

For desert, we ordered rasgulla (NT$90) as gulab jamun wasn’t available. Two white balls come soaked in a little pool of syrup. To really relish the heady-sensation it offers, rasgulla, like gulab jamun, should be taken in one bite. One bite of heavenly bliss. The ball’s sponginess resists the weight of your jaws as they slowly clamp down, letting the syrup slowly ooze and flow out over your teeth and tongue. The sponge becomes firmer as you push into the core before finally splitting and filling your cavity with a sugary mouthful of sinful proportions.

I wish the rest of the meal had delivered similar levels of sensory satisfaction, but all in all, it was hit and miss. At just over a year old, Saathiya is a new arrival on Taipei’s indistinct Indian scene, and like a toddler, still trying to find its feet. Above the MRT, it’s very accessible and a stroll around the pretty backstreets of Dongmen is nice after dinner. Yet I wouldn’t go out of my way to come back to Saathiya.

Photo: Liam Gibson

Photo: Liam Gibson

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the