Sept. 11 to Sept. 17

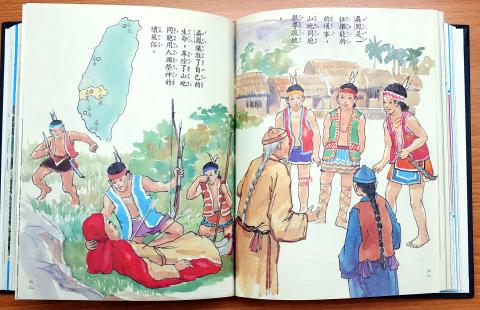

For almost a century, Wu Feng (吳鳳) was known as a selfless, compassionate hero. Under both Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) rule, every child read in school about how Wu sacrificed himself to stop Aborigines from their “savage and backward headhunting practices.”

Here’s the gist of the story: Wu spent much time with the Tsou Aborigines in what is today Chiayi County, teaching them how to farm and make crafts. After trying to delay their headhunting ritual to no avail, Wu told them to decapitate a man in red clothes who would pass by the next day. They did so, only to find that the man was Wu himself. Shocked and deeply saddened, the Aborigines vowed to give up the practice forever.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Students today are likely oblivious to this figure, as on Sept. 12, 1989, Minister of Education Mao Kao-wen (毛高文) agreed to remove Wu’s story from the textbooks.

REVERED FIGURE

It was a drastic fall. Four years earlier, the Wu Feng Temple (吳鳳廟) in Chiayi had held a grandiose celebration for the opening of Wu Feng Memorial Park to celebrate the 216th anniversary of Wu’s selfless act. The park soon lost its original name and became a cultural amusement park that went out of business in 2010.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The commemorative 1985 book Wu Feng, The Righteous Man (義人吳鳳) contains songs, poems and submitted essays praising Wu’s character and his determination to “civilize our mountain compatriots.” There’s a curious disclaimer that the group of Tsou people who killed Wu no longer exist and have nothing to do with the modern Tsou.

“The highest state of being for mankind is to selflessly help others. Wu Feng was able to [achieve this] because he understood love, he understood devotion, he understood bloodshed, he understood sacrifice and he understood death,” read one passage.

Many of the essays attributed Wu’s upstanding morals to Chinese culture while demeaning the Aborigines as inferior people.

Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei Times

“Wu Feng was the first Han Chinese to give the mountain compatriots human rights. Throughout history, whenever Chinese culture came in contact with barbarians, it always used the method of gradual and natural assimilation. Wu Feng lived in savage lands but he did not let his superiority get the better of him. Instead, he did all he could to improve the lives of the mountain compatriots,” wrote schoolteacher Huang Kun-yuan (黃崑源).

“The reason Han Chinese culture has been able to survive for thousands of years while absorbing weaker and inferior races is because of the Confucian virtues of compassion and righteousness,” wrote Yan Ming-hsiung (顏明雄), also a schoolteacher.

“Wu Feng sacrificed his life to change the bad habits of the Aborigines. This is because of the virtues that have been present in Chinese culture since ancient times ... We should carry forward the spirit of our people.”

On a side note, almost every essay ended with something along the lines of “we must apply Wu Feng’s spirit to our lives so we can defeat the Communists and reclaim the mainland.”

FROM HERO TO ZERO

The first known account of Wu’s tale, published in 1855, was very different from the version found in the textbooks. It was a simple tale of how Wu volunteered to die for two Han Chinese villagers after asking them to flee. After his death, his ghost haunted the Aborigines and brought them great sickness. Terrified, the Aborigines vowed not to kill any more Han Chinese in that area and paid tribute to Wu’s grave every spring and fall.

The story then becomes more elaborate. During the Japanese colonial era, Wu’s motives went from protecting his people to “civilizing the savages.” The purpose was manifold: to discourage Han Chinese from fighting against other races, to show that Aborigines can be civilized through kindness and also serve as an example for colonial officials. The tale was made into movies, plays and entered elementary school textbooks.

The KMT adopted wholesale the Japanese version of the legend into its textbooks, promoting Wu as a beacon of Chinese virtues that people should look up to.

But to Aborigines, it brought feelings of shame.

“As a half Aborigine, I felt angry when I read this story. I was angry that I had the blood of such an uncivilized people in me,” writes Huang Hsiao-chiao (黃筱喬) in the study Sense of Identity Beginning from Wu Feng (身分認同從吳鳳說起). Others spoke in various reports of being looked down upon because of the story and even attacked by Han Chinese children who wanted to take revenge for Wu Feng.

Wu’s downfall began in 1980, when anthropologist Chen Chi-nan (陳其南) wrote an article for the Minsheng Daily (民生報) titled A Fabricated Legend: Wu Feng (一個捏造的神話: 吳鳳).

The Aboriginal rights movement soon took off, and during the 1985 ceremony, several Aborigines showed up wearing white shirts that read: “Wu is not a hero” and “Wu Feng’s story is the shame of education.”

The rectification of Wu Feng’s story became a focus of Aboriginal protests, and in 1988, local pastor Lin Tsung-cheng (林宗正) led a group of Aborigines and destroyed the Wu Feng statue in front of Chiayi train station with a chainsaw.

At least one of Wu’s descendants, ninth-generation descendant Wu Liao-shan (吳廖善), didn’t seem to mind.

“It doesn’t really matter to me whether Wu Feng’s story remains in the textbooks or not,” Wu Liao-shan told the media. “The Aborigines say that the story causes people to look down on them, to bully them in school, so I guess it’s for the best to not include the story. But really, this is a problem with the teachers. They should teach their students not to bully others. Then we wouldn’t be facing this problem.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

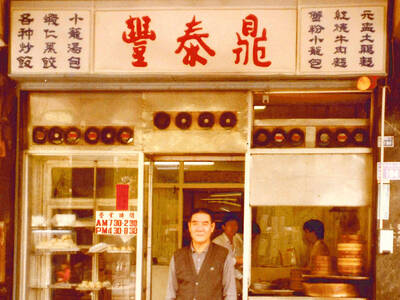

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

For the past century, Changhua has existed in Taichung’s shadow. These days, Changhua City has a population of 223,000, compared to well over two million for the urban core of Taichung. For most of the 1684-1895 period, when Taiwan belonged to the Qing Empire, the position was reversed. Changhua County covered much of what’s now Taichung and even part of modern-day Miaoli County. This prominence is why the county seat has one of Taiwan’s most impressive Confucius temples (founded in 1726) and appeals strongly to history enthusiasts. This article looks at a trio of shrines in Changhua City that few sightseers visit.