It’s that time of year once again: incense burners and tables of offerings dot Taipei’s sidewalks, and the local temples are even more vibrant and busy than usual, while swimming pools and beaches aren’t quite as packed as they should be, considering the heat.

The seventh month of the lunar calendar (better known as Ghost Month) began on Tuesday of last week and for the following 29 days, countless Taiwanese must observe a whole host of taboos, in addition to making daily offerings to the “good brothers” (好兄弟): the ghosts of the dead who have been temporarily released from the underworld to wander among the living.

Although Ghost Month is observed by many throughout the world’s Chinese-speaking communities, it’s observed with special diligence in Taiwan. Over the centuries the country has attracted large numbers of fishermen, miners and other manual workers from China and elsewhere, many of whom died from disease, accident or other reason, far from their families. Without any kin to conduct the proper rites, they are restless and walk the earth during Ghost Month, causing mischief or trouble for the living if they are not appeased.

Photo: Richard Saunders

HAUNTED HARBOR — KEELUNG

The port city of Keelung on the north coast has the most active and vivid program of Ghost Month observations due to a historic event that ensured it has more than its fair share of “good brothers.”

During the Qing Dynasty, an influxe of Fujianese immigrants arrived from China. Many settled in the Keelung area, and soon disagreements arose between the population over land, business and religious customs. This discord culminated in a major clash in 1851, which left many dead or injured. A truce was negotiated, and to appease the souls of the dead, representatives of 11 families involved agreed to take turns organizing rites and offerings to the dead: the first ritual took place in 1856, and the custom has continued to this day.

Photo: Chien Hui-ju, Taipei Times

By far the most colorful of Keelung’s Ghost Month events is the Parade and Releasing of the Water Lanterns. Around dusk on the evening of the 11th day of the seventh lunar month — Sept. 4 this year — a procession of colorfully decorated floats parades around the center of Keelung.

Representatives of the 11 families walk through the streets behind large banners emblazoned with the Chinese character of their family name. Look out for the elaborate paper lanterns, in the shape of houses, carried aloft on palanquins by members of each clan’s procession. These, which lie at the heart of the evening’s festivities, are destined to become houses for the good brothers, and will be pushed out into the East China Sea and burned during the climax of the evening.

The procession winds down between 9pm and 10pm, and then everyone heads over to Wanghaisiang Bay (望海巷) at Badouzi (八斗子), nine kilometers east of Keelung Railway Station, to see the highlight of the night’s activities: the burning of the water lanterns. Shuttle buses are available from the city center. The burning ceremony starts at around 11pm, but try to arrive well before this, to snag a good spot. Aim for a spot as far to the right as possible, close to the boat ramp, where the lanterns will be set adrift.

Photo: Richard Saunders

The lantern burning ritual is over within 15 minutes, after which there’s a sudden exodus as everyone boards the fleet of shuttle buses back to Keelung. If heading back to Taipei, check the times of late trains and buses in advance with the tourist office at Keelung station, as extra transport may be added after midnight.

CLIMB-ACTIC FINISH

While Keelung’s Ghost Month festivities are colorful, without doubt the most extreme event of the month takes place on the last day in Yilan County’s Toucheng Township (頭城), an hour or so from Taipei by bus or train. For the participants, Ghost Grappling Festival (搶孤), which falls on Sept. 19, is easily the most dangerous of all major Taiwanese festivals, and it was actually banned for years before being revived (with improved safety measures) in 2004.

Photo: Richard Saunders

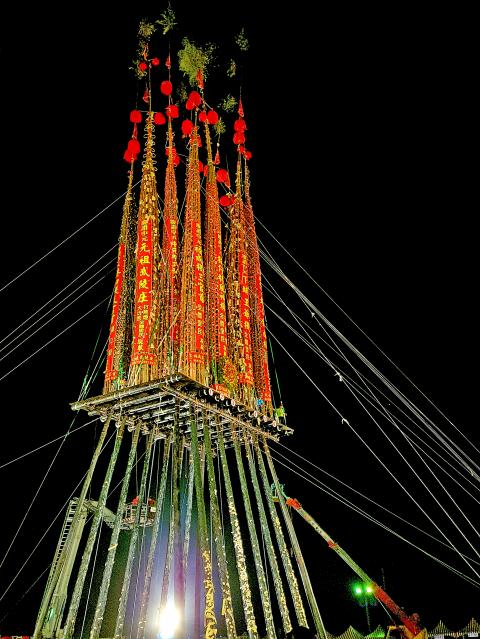

The ritual venue, on the southern edge of town, is dominated by a great tower called a gupeng (孤棚). The lower portion consists of 12 thick poles nearly 20 meters tall, made from the trunks of fir trees; the trunks are liberally greased with beef fat to make climbing them even harder. On top of these is a large platform on which stand 13 towers made from multiple lengths of bamboo bound together, soaring into the floodlit night air. Various offerings such as dried squid, glutinous rice dumplings and pastries are tied to the poles. At the top of the towers are 13 “fair wind flags” (順風旗).

The main event begins at about 11pm, and unlike Keelung’s big night two weeks earlier, there’s no large pre-ritual procession through the streets to enjoy. However, arrive several hours early if you want to secure a good view, before camera and tripod-totting photographers grab all the pole positions.

After the long wait, the contest begins around 11pm. At the whistle, 12 teams of five people race to the base of the greased pole assigned to their team, and climb on one another’s shoulders in an attempt to scale the pole. Once at the top of the pole (where attendants fix safety lines onto the competitors), there’s a desperate struggle to get out and over the edge of the overhanging lip of the platform above. Once safely on top, the successful climbers begin the second stage of the climb, scaling one of the 20-meter-tall bamboo towers standing on the platform.

Photo: Richard Saunders

At the top of each tower is a single slender stem of bamboo, crowned with a red paper lantern and a flag, which must be cut down. The winner is the person to cut down the first flag. At the end of the event, the crowd scrambles to catch one of the plastic-wrapped pastries and other goodies thrown at them from the platform in a ritual that was originally intended to symbolize giving alms to the poor.

Suddenly it’s all over, and the crowds make a beeline back to Toucheng Railway Station, 15 minutes’ walk away, while those who planned beforehand make their more leisurely way back to the hotel they booked a month or two in advance.

Photo: Lin Hsin-han, Taipei Times

Photo: Tsai Cong-Hsien, Taipei Times

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern