During the past three decades, the perception of Taiwan’s history has undergone a significant change. In the traditional perspective, Taiwan and its history were closely linked to China, particularly its coastal province of Fujian, from where the majority of the population migrated in the 17th and 18th centuries.

This linkage with China was reinforced after 1949 during the period of rule by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) who wanted to strengthen their perception that Taiwan had historically been an integral part of China. In high schools and universities, children were taught Chinese history and geography, while the KMT authorities neglected, or even suppressed, Taiwan’s history.

This started to change after the nation’s momentous transition to democracy in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when presidents Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) and Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) initiated educational reforms that included history and geography of Taiwan in the curriculum. In 2015 there was an effort by the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) administration to return to a Sino-centric perspective, but this ran into strong opposition from high school students who went into the streets to block Ma’s moves.

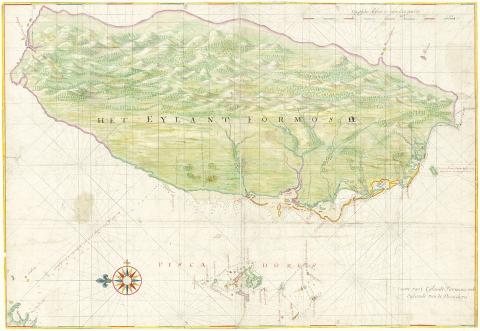

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

TAIWAN at the center of its HISTORY

So, what is new in the history of Taiwan as we see it now, and how is this different from the previous perspective? There are three aspects. First, the close connection between Taiwan’s Aboriginal population and the original people of the Pacific islands, including New Zealand and Hawaii, going back more than 3,000 years.

Secondly, the fact that during the period of Dutch colonial rule (1624-1662), Taiwan — and in particular the harbor of Tayouan (Anping District (安平) in present-day Tainan) — was a major and prosperous international trading post, linking Taiwan to Japan, Southeast Asia, and as far as India and Persia. Taiwan was “connected to the world” in that first phase of globalization.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Thirdly, it wasn’t until the rule of Koxinga (Cheng Cheng-kung, 鄭成功), the Ming-dynasty warlord and pirate chieftain, that Taiwan — for the first time in its history — became more closely connected with the Chinese coastal provinces. Prior to the Dutch era there had been scant interaction with the coastal provinces.

‘THE GREAT MIGRATION’

During the past three decades, linguistic and DNA research has presented evidence that Taiwan was the main source of “The Great Migration,” starting around 3,000 BC, which eventually populated almost all of the Pacific. This research placed Taiwan’s indigenous people to be at the origin of almost all original inhabitants of the Pacific archipelagos such as Micronesia, Polynesia and Melanesia.

In addition, archaeological work in Taiwan and elsewhere in Asia has shown the existence of extensive trading networks between Taiwan and Southeast Asia as early as 2,800 BC to 2,200 BC. Taiwan’s early connections to the Pacific and Southeast Asia are thus well established, and are the basis for seeing Taiwan as an “Ocean nation.”

DUTCH RULE

Much more has become known about the period of Dutch colonial rule of Taiwan in the 17th Century. In the mid-1980s, a team of researchers headed by Leonard Blusse of Leiden University started to publish the official records of the Dutch East India Company’s reports by the Dutch governors and local officials at Fort Zeelandia (in today’s Tainan), the headquarters of the “Vereenigde OostIndische Compagnie” (VOC, Dutch East India Company) in Formosa (Taiwan) from 1624 to 1662.

These reports provided a whole new generation of researchers with ample material on the interactions between the Dutch and the Aboriginal population, as well as the Hokkien immigrants who started to migrate from the coastal province of Fujian during the Dutch period. The research was initiated in the 1960s and 1970s by Tsao Yung-ho (曹永和), a librarian at the National Taiwan University Library, but didn’t become mainstream until the 1990s.

This newly available material led to a new wave of publications between the early 2000s and the present. Much of this focused on the 17th-century interaction between the Dutch and both the indigenous people as well as the Hokkien immigrants, as well as the struggle for power between the Dutch and Ming Dynasty warlord Koxinga who himself was on the run from the Qing Dynasty, which had come to power in 1644.

PROTO GLOBAL ECONOMY

There is however a fourth aspect which does deserve more attention in academic research, and in how the Dutch period is perceived in the context of Taiwan’s history: Taiwan’s connection with, and integration in, the world economy in the 17th Century.

Taiwan itself became the source of a number of important trading goods, initially deer hides. Aboriginal hunters would hunt the deer, sell the hides to Dutch traders who would sell them in Japan to Samurai warriors who prided the tough deerskins for their armor and shields. However, over-hunting gradually depleted the deer-stock and the trade diminished after 1650.

But from 1635 onward, the Hokkien settlers started to produce rice and sugar, which in the 1640s and 1650s became major export products, shipped by the Dutch to as far away as Japan, India and Persia.

This major increase in trade between Taiwan and the rest of the world was accompanied by increasing interest elsewhere in Taiwan: writers and mapmakers literally started to “put Taiwan on the map.” The National Palace Museum in Taipei did a major exhibition on this topic in 2003: The Emergence of Taiwan on the World Scene in the 17th Century.

NEW FRONTIER

However, subsequent events would significantly reduce this high connectivity between Taiwan and the rest of the world. As described earlier, Koxinga was driven into a corner by the invading Qing/Manchu Dynasty, and in 1661 crossed over to Taiwan, driving out the Dutch after a nine-month siege of Fort Zeelandia.

During the 1662-1683 reign of Koxinga’s successors (he himself died four months after his victory over the Dutch), many more immigrants from the coastal provinces came to Taiwan to escape war and hunger and start a new life at the new frontier. At the end of the period, there were some 100,000 Hokkien immigrants, and interaction with the Fujian homeland became the main focus of Taiwan’s economic life.

This only intensified after 1683, when Koxinga’s successors were defeated by Qing Dynasty troops under Qing Admiral Shih Lang (施琅), who eventually convinced Qing Emperor Kangxi (康熙帝) to agree to the conquest of Taiwan, but who himself was eyeing rich farmlands around Tainan. During the subsequent 200 years, trade and the movement of people were primarily focused on China’s coastal provinces, thus narrowing its interactions and exchanges with the outside world.

This international isolation only ended in the latter half of the 19th Century, when the event of steamships made long-distance travel easier, and Taiwan again became the focus of international attention. This eventually led to the formal transfer of the sovereignty over the island under the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, when the Qing government in Beijing ceded Taiwan to Japan, without consulting the island’s population.

Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat who also served as editor of ‘Taiwan Communique,’ a publication in Washington DC. He currently teaches history of Taiwan at George Mason University.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern