May 8 to May 13

Shortly after the Japanese took Keelung during its takeover of Taiwan in 1895, Lin Chao-tung (林朝棟), patriarch of the prominent Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家), disbanded his resistance troops and set sail for the Qing Empire’s Fujian Province — from where his ancestors came 149 years previously.

Lin never returned to Taiwan, but he made sure that family members remained or returned to Taiwan to manage their wealth and cooperate with the Japanese, and the Wufeng Lins continued to thrive in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

DEADLINE TO LEAVE

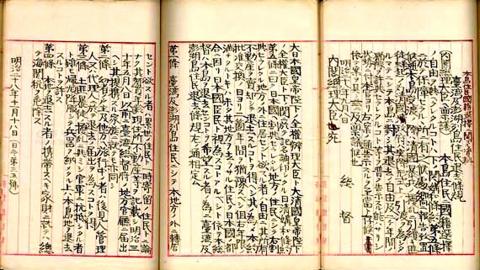

A provision in the treaty of Shimonoseki, which signed Taiwan and Penghu over to Japan, stated that residents of Taiwan had until May 8, 1897 to depart for Qing territory — those who stayed would automatically become Japanese citizens. This option, according to an article for the National Taiwan Library by Wu Chun-ying (吳俊瑩), was not offered to Aborigines. Those who left would have their property taken by the government if they didn’t leave someone behind to manage it — and it is known that the Japanese used the deadline to compel Lin Wei-yuan (林維源, of an unrelated Lin clan), to send two nephews back to Taiwan and accept Japanese citizenship.

The number of people who left Taiwan before that deadline varies by source, with an 1897 government document recording a total of 6,546 departees. Wu writes that the majority of these were upper class intellectuals who had close ties with the Qing and would lose their elite status if they remained. Huang Fu-san (黃富三) writes in the study The Effect of Japanese Rule of Taiwan on the Wufeng Lin Family (日本領台與霧峰林家之肆應) that to a lesser degree, landowners and merchants also fled.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“The wealthier and closer to the Qing government, the more likely they were to leave,” he writes.

Wu adds that people likely stayed for practical reasons, not because they supported the Japanese government.

Huang writes that many found it difficult to make a living in China and returned to Taiwan before the deadline, although the Japanese did continue to offer citizenship to some Taiwanese who decided to return later. For example, Lin Chao-tung’s cousin Lin Chao-sung (林朝崧) returned to Taiwan in 1897 because of “homesickness and economic hardship.” During this period, people appeared to be able to move back and forth freely; Lin Chao-sung wrote several poems about his regret and sorrow in becoming a Japanese subject and left for China again shortly after, only to return in 1898.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

RETURNING TO TAIWAN

Huang writes that Lin Chao-tung had much reason to flee as a former Qing official. Lin was involved in the Republic of Formosa’s resistance against Japanese rule, but arranged for his immediate family to flee to Fujian as the Japanese landed. When Lin found out that the republic’s president had fled to China, he disbanded his troops and departed as well. He ordered his cousin Lin Shao-tang (林紹堂), who remained in Taiwan, not to resist the Japanese, and the Lin family was relatively unharmed as the Japanese marched through Wufeng.

“The Japanese would peel away at the special privileges of these prominent families, but they also allowed the ones who submitted to the colonial government to retain their wealth and prestige to a certain degree,” Huang writes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lin refused to return to Taiwan, but many of his kin did. He reluctantly ordered several sons to head home and become Japanese subjects to keep their land and manage their fortune. Unable to return to politics, the family diversified their ventures and also became notable philanthropists.

“It appears that the Lin family had essentially accepted Japanese rule by then, only aspiring to excel in the economic and social realms,” Huang writes.

Huang adds that although the Lin family thrived in Taiwan, they frequently visited China, promoted Chinese education in Taiwan and also formed Chinese poetry associations — likely to soothe their feelings of submitting to a foreign power.

After Lin Chao-tung died in 1904, his son Lin Tzu-keng (林資鏗) returned to China to inherit his father’s imperial rank. He was reportedly involved in anti-Japanese activities on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, finally renouncing his Japanese citizenship and joining the newly-formed Republic of China in 1913. The Dr. Sun Yat-sen Academic Research Site states that he was the first Taiwanese to become a Republic of China citizen. The Japanese confiscated large amounts of family property in response. He joined Sun Yat-sen’s (孫逸仙) Chinese Revolutionary Party, playing an important role until his death in 1925.

After Lin Tzu-keng’s departure, Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) — who also briefly left for China and returned — became head of the family. He would become an important political activist, continuing the resistance in his own way.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,