March 13 to March 19

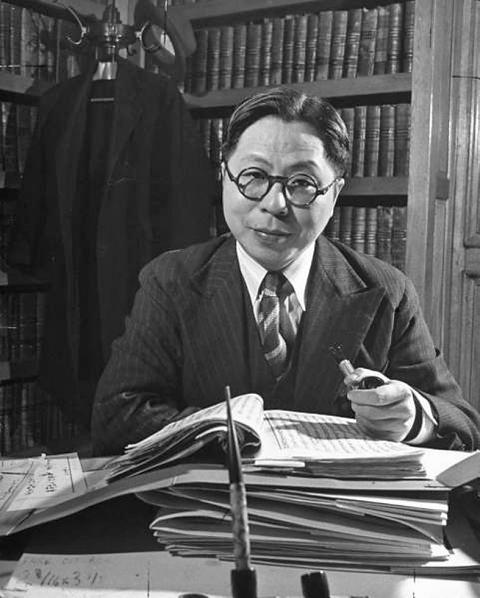

On March 17, 1954, K.C. Wu (吳國楨) was stripped of his Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) membership and relieved of all his duties. Not that he was performing any of them — by then, he had resigned his post as governor of Taiwan and fled with his family to the US after a prolonged conflict with other party members, including Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), son of then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

The move came after Wu noticed on a road trip in March 1953 that the front wheels of his car had been tampered with, which he saw as an assassination attempt. Two months later, he successfully left the country under the pretense of nursing a sickness and accepting an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, Princeton University.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I’m not coming back,” he reportedly told Judicial Yuan president Wang Chung-hui (王寵惠), who came to see him off at the airport.

GOING PUBLIC

Wu kept quiet at first — he was invited to speak at a Double Ten National Day gala in New York City, but only talked about supporting the Nationalists’ fight against Communism. But in November, reports surfaced accusing him of using government money to live a luxurious life in the US. He spent the next three months trying to clear his name, which garnered him more media attention.

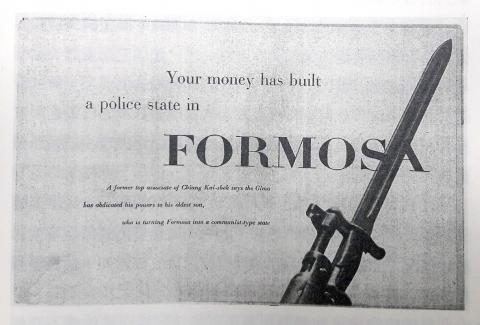

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

He started to reveal more — when asked by Chicago’s WGN-TV why he came to the US, he replied that it was for both health and political reasons. Before that, however, he had maintained that it was entirely due to his sickness.

“In the political climate of those times, this was essentially a public challenge to Taiwan’s government,” his biography published by the Liberty Times states. CBS sent a reporter to his house the next day, and “there was no going back.”

On Feb. 16, 1954, he completely opened up about his conflict with the government, one of the points being that they did not care to win the support of the Taiwanese as well as overseas Chinese.

Liberty Times file photo

“We also need to win the support of free countries, especially the US. But if we don’t practice true democracy in our territories, this will not happen,” he said.

According to his biography, he then repeatedly told reporters in English, “The present government is too authoritarian.” These words made the major US newspapers.

This started a war of words between Wu and the KMT across the Pacific Ocean, leading up to his expulsion from the party.

SIMMERING FEUD

Wu had worked for the KMT since 1926 and was once a close associate of the Chiang family. He retreated to Taiwan with the KMT in 1949, and in 1950 he became governor after Chen Cheng’s (陳誠) resignation.

During this time, he clashed with other major KMT members over many issues, including greater self-governance for Taiwanese and increased democracy. The book Who’s Afraid of Wu Kuo-chen? (誰怕吳國楨?) by Yin Hui-min (殷惠敏) states that he even directly brought up the idea to Chiang Kai-shek of allowing multiple political parties.

“We have the best people on our side, where would we find able people to form an opposition party?” Chiang reportedly replied.

Wu had clashed with Chiang Ching-kuo while still in China, and this feud continued in Taiwan when he intervened in a mass arrest by Chiang’s special agents. Several more incidents took place over political arrests, and Wu further incurred Chiang’s wrath by refusing to provide funds to the anti-communist youth organization China Youth Corps (救國團), which he compared to communist and Nazi youth leagues in his biography.

Unable to carry out his political ideals and unhappy with the direction the Chiangs were going toward, Wu tried to resign several times, but to no avail. Chiang Kai-shek was intent on passing on power to his son, and was hoping that Wu would support him. Wu refused, and finally Chiang Kai-shek had no choice but to accept his resignation.

After his expulsion from the party, Wu only amped up his rhetoric, writing several letters to Chiang criticizing the government’s one-party rule, political intimidation through special agents and lack of press freedom among other issues.

He also accused Chiang of nepotism, saying that he “loves power more than his country, and loves his son more than his people.”

Probably most notable is the article he penned for Look magazine, titled Your Money has Built a Police State in Formosa, stating that Taiwan has turned into a “communist-type state.”

However, Wu’s efforts did not deter the US from continuing to support and provide funds to the KMT regime. As George H. Kerr writes in Formosa Betrayed, it was the height of the McCarthy Era and the US was more concerned about fighting communism, and “Wu’s voice was drowned in the clamor of more aid for Chiang.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual