March 6 to March 12

Last month, the family of the late poet Tu Pan Fang-ko (杜潘芳格) donated 340 manuscripts to the National Central Library. The three languages these documents were written in — Japanese, Mandarin and Hakka — represent Tu Pan’s literary journey through Taiwan’s turbulent history.

Living through the Japanese and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) regimes, the political climate dictated what language Tu Pan wrote in for most of her life. It wasn’t until she was in her 60s that she began to use her native Hakka.

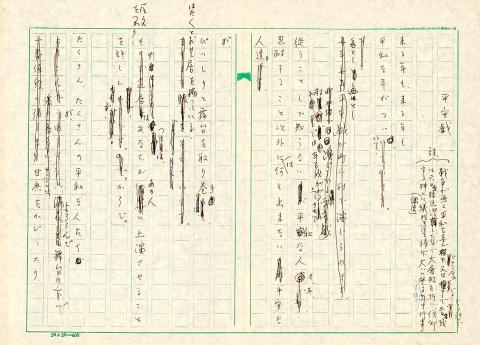

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Writers like Tu Pan are often included in the “translingual generation” (跨語言的一代), a term coined in 1967 by poet Lin Heng-tai (林亨泰) to describe those who were educated in Japanese but were forced to pick up Mandarin under KMT rule. He specifically referred to those who came of age under the colonial government’s Japanifcation policy, which officially began in 1936.

“When Japanese rule ended, we were in our 20s. Unlike the older generation who may have had some exposure to an education in Chinese, we were strictly educated in Japanese since childhood. While we were no longer forced to speak Japanese, it was the language we were most comfortable writing in. We had to be determined enough to make another shift, which was to learn Chinese,” he wrote.

A National Museum of Taiwan Literature publication states, “This was especially problematic for writers, as they lost their rich vocabulary, grammar and ability to express complex thoughts. Many stopped writing, and others had to study for years before they could write in Chinese.”

Photo: Chen Yi-min, Taipei Times

But like other members of this generation, being forced to use a new language did not dampen Tu Pan’s literary passion.

“If you ask me why I write, you might as well ask me why I live,” she said in a 2004 interview with Ink Literary Monthly (印刻文學生活誌). “My words have a life of their own … they simply appear, and I’m compelled to write them down.”

Born on March 9, 1927 to wealthy and educated parents, Tu Pan’s family moved to Japan when she was an infant. They returned when she was about six years old, and enrolled in Japanese schools up to the college level. Her work is shaped by many conflicts in her life — being bullied by Japanese schoolmates, questioning the role of women in society, defying her parents’ wishes by choosing her own husband and losing several family members in the 228 Incident.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The KMT banned writing in Japanese in 1946, and Tu Pan did not publish anything for more than a decade. She was also busy helping her husband and raising seven children during this time. In 1966, she published her first Mandarin poem, written in Japanese and translated by fellow writer Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流).

Most of her early works in Mandarin were translations of Japanese originals. Lee Yuan-chen (李元貞), a professor of Chinese literature, writes that they often suffered at the hands of various translators, who were often male and did not grasp the nuances of the female perspective.

“This is one of the reasons she wasn’t as influential as she could have been,” Lee writes. “Such is the fate of many members of the translingual generation.”

NATIVE TONGUE

After the lifting of martial law in 1987, Hakka intellectuals founded Hakka Affair Monthly magazine (客家風雲) and held a “Return My Native Language” (還我母語) march on Dec. 28, 1988.

Tu Pan was never fully comfortable writing in Mandarin, and Japanese remained the main language she used during the creative process. One day, however, she noticed that “some verses started to naturally form in my native Hakka.”

“I picked the words up and wove them into Hakka poems,” she continues. “But it was difficult, as I had a limited literary vocabulary.” Figuring out how to write down Hakka sayings that did not have Mandarin counterparts was also a challenge.

She published her first Hakka poem in 1989, and soon it became a mission to help keep the language alive.

“It is time for some soul-searching as we Hakka people are being assimilated by other groups,” she wrote in a 1994 column for The Commons Daily (民眾日報). “We should love our native language and find ways to improve it and turn it into an elegant and beautiful language … I hope that Hakka writing can develop and become a trend.”

She says she wanted to follow the example of Dante, who wrote The Divine Comedy in Italian instead of the prevalent Latin, adding that if the work becomes popular enough, the language it uses will increase in prestige.

In addition to new pieces, she also reworked some of her old poems in Hakka, which were often not straight translations. The original 1977 Mandarin version of Peace Play (平安戲), for example, doesn’t include a Hakka-specific euphemism that the 1995 Hakka version does.

Tu Pan then penned several poems stressing the importance of speaking one’s mother tongue. After it became acceptable to speak in languages besides Mandarin, she also became worried that Hakka was losing ground to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese).

“Recently, everybody is speaking Taiwanese … But there are many types of Taiwanese. Aboriginal languages and Hakka are also Taiwanese,” she wrote in a 1993 piece.

And after writing for her entire life in Japanese and Mandarin, she denounced the two languages:

“[They] are two languages that we were forced to learn by authorities, and represent our enslavement. Mandarin and Japanese are merely a common means for us to communicate — it is not our native language. We Taiwanese have been culturally assaulted for 100 years; our language taken away by outsiders.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,