Feb. 20 to Feb. 26

About 500 Tao Aborigines from Orchid Island marched toward the southeastern tip of their homeland on the morning of Feb. 20, 1991, raising placards and announcing their desire to rid the island of “evil spirits” — nuclear waste.

This was the third Feb. 20 protest on the island since 1988. The island’s inhabitants say that the waste storage facility was built without their permission and poses a serious threat to their health and the environment.

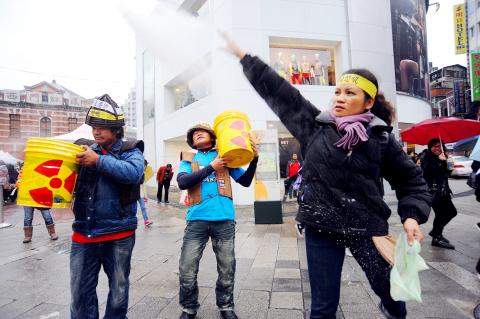

Photo: Chang Tsun-wei, Taipei Times

“This land has a soul, which has protected our tribe. Now, nuclear waste is poisoning it. If we don’t fight back, the damaged land will in turn hurt us because we did not fulfill our responsibility to protect it … Although we choose to protest peacefully, we wear full warrior costume to show our determination to keep fighting,” said protester Syaman Jyavitong.

According to an Orchid Island Biweekly (蘭嶼雙週刊) report, one elderly islander cried during the first protest. “If they keep saying it is so safe, why don’t we each take a barrel and keep it in our houses? Why do we need a storage facility?”

Indeed, when the facility was first built, state-run Taipower Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and government officials repeatedly assured the islanders that the waste was harmless. Orchid Island writer Syaman Rapongan recalls that he was told that “it was safer than hugging two gas barrels while sleeping.”

Photo: Chang Jui-chen, Taipei Times

The Atomic Energy Council launched several “educational” initiatives and set up a nuclear energy exhibition in Taitung to further convince the islanders, but they did not appear swayed.

In response to his people’s plight, Syaman Rapongan penned this poem: “Wild savages, your breakfast is served. Cobalt-60 for the men, cesium-137 for the women. As for the children, their breakfast is extinction.”

KEPT IN THE DARK

Photo: Lo Pei-Der, Taipei Times

How did the facility come about? In August 1971, the Atomic Energy Council met with Taipower and other institutions to discuss what to do with the waste produced at what would be Taiwan’s first nuclear power plant, approved by the government the previous year.

According to a study, The Mobilization of Orchid Island’s Anti-nuclear Movement (蘭嶼反核廢場運動的動員過程分析), by Wang Chun-hsiu (王俊秀), the best option was to dump it in the ocean — but given Taiwan’s declining international standing, they did not want to upset their neighbors. The next best option was to store it on an island.

The committee looked at 14 candidates — some were too small, some didn’t have harbors, some were too developed and some too close to the mainland — finally deciding on Orchid Island.

“The committee considered safety and economic factors, but not public opinion,” Wang writes. “They never informed the Tao people of their plan, and only started communicating with locals under public pressure.”

The committee did consider eventually dumping the waste into the ocean, but that plan was made invalid with the 1975 enforcement of the London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter.

Wang writes that the Tao people were kept in the dark for almost a decade, finally finding out through media reports in 1982. Wu Jui-lan (吳瑞蘭) writes in A Study of Public Participation in Policymaking (政策的制定與民眾參與之研究) that when construction started, nobody was clear on what was being built — some said a fish cannery, others a military port — but none would have guessed a nuclear waste facility.

RESISTANCE

The first 10,008 barrels of waste arrived on Orchid Island in 1982. The first time the Tao people publicly expressed their displeasure was in 1987, when a group of young men tried to stop the Atomic Energy Council from giving a tour of the facility.

The official resistance began on Feb. 20, 1988 when 200 islanders staged the first “Chasing Away Evil Spirits” protest, and two months later the Orchid Island Youth Friendship Association (蘭嶼青年聯誼會) sent 100 members to support the anti-nuclear protests in front of the Taipower Building in Taipei.

Wang writes that since most Tao people did not understand what nuclear waste was, the young protesters dubbed the facility an anito, or evil spirit, to show other islanders the graveness of the situation.

“When they hold ceremonies to get rid of evil spirits, they must channel their greatest anger,” he writes. “The goal was to show how truly terrifying the facility was.”

In 1996, angry islanders successfully stopped a ship carrying 168 barrels from docking. No more ships would come after that, but almost 100,000 barrels remain on the island.

Protests continued and the issue heated up again when Taipower’s contract for the land expired on Dec. 31, 2011, leading to another Feb. 20 protest in 2012.

Today, the waste is still on the island, and the issue is slowly making headway. Just last week, the Ministry of Economic Affairs announced that it hopes to finalize its decision on a new site this year. Meanwhile, the Tao people continue to wait.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the