Jan. 23 to Jan. 29

Chiang Sung-hui (蔣松輝) waited until the regular staff at the telegram office got off work. The remaining workers did not understand English, and this was the Taiwan People’s Party’s (台灣民眾黨) best chance to get their message, written in broken English, to the League of Nations.

The one-sentence telegram accused the Japanese colonial government of relaxing opium prohibition rules and asked the League to intervene.

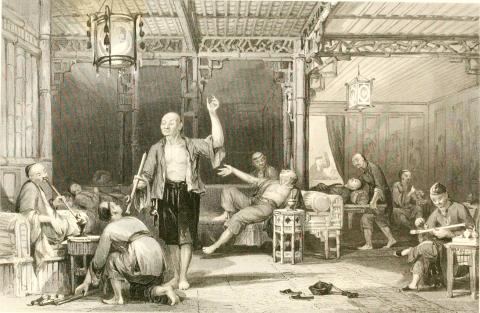

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Since the Japanese had a monopoly over the production and sale of opium in Taiwan, the party believed that they’d never had any intention of eradicating the social vice despite vowing to do so 35 years previously, in 1895.

Upon taking over Taiwan, the Japanese pushed a “gradual prohibition” policy by issuing licenses to a limited number of qualified smokers. The government seemed to be on the right track as the number of legal smokers dropped, and in 1912 they signed the International Opium Convention, which mandated that signatories “use their best endeavors to control, or to cause to be controlled, all persons manufacturing, importing, selling, distributing and exporting” drugs such as opium.

Japan stopped issuing new opium licenses in 1908, and the number of legal users dropped dramatically. The government’s opium monopoly remained lucrative as they raised prices every year, but it no longer occupied such a large proportion of the colony’s total revenue as the economy diversified.

After the 1925 Geneva Opium Convention, the government in 1928 announced plans to close down smoking locales and build addiction treatment centers. But in 1929, an amendment was added, proclaiming jail time for illegal addicts. It also announced that they could apply for a license, declaring that it was more humane.

“If we allow opium addicts to destruct on their own, it will be a dark blemish on our glorious policies,” the announcement concluded.

This sudden decision to issue licenses to about 25,000 additional users further raised suspicions among Taiwan People’s Party leaders, who had been calling for immediate prohibition for years. They started a colony-wide campaign, making public speeches and repeatedly protesting the new provisions.

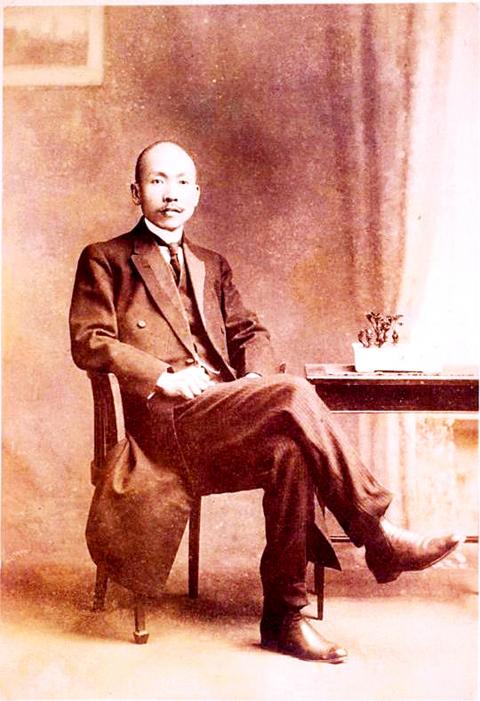

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Taiwanese physicians also joined the fight. A Tainan Medical Association petition requested that the governor-general issued additional licenses only to addicts whose lives would be threatened if cut off. They also called for medical examinations for license holders to deem whether they were treatable — and if so, they should be rehabilitated by force. They also asked the government to limit all smoking activities to state-run opium houses.

Investigators from the League of Nations arrived on Feb. 19, 1930. They were on an eight-month trip to Asia to investigate the region’s drug use, and their arrival was most likely not in direct response to the telegram. Nevertheless, despite government objections, the investigators met with party leaders Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) and Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) on March 1 to discuss the problem further.

Although the government did not change course, Lo Ming-cheng (駱明正) writes in the book Doctors without Borders: Profession, Ethnicity and Modernity in Colonial Taiwan, the Taiwan People’s Party’s criticisms “were widely circulated in the media and were greatly influential.”

Photo courtesy of Sanlih Entertainment Television

“[For] the new generation, smoking opium was seen as the result of state manipulation rather than merely the continuation of a traditional habit,” he adds.

However, wanting to maintain its international image, the government finally started to actively treat and rehabilitate addicts. The effort was led by physician Tu Tsung-ming (杜聰明), who worked tirelessly for years, reportedly curing Taiwan’s “last opium addict” in 1946.

A side episode from this incident was the downfall of noted intellectual and historian Lien Heng (連橫), the grandfather of former vice president Lien Chan (連戰), who publicly supported the government’s stance in an editorial in the local newspaper. It began by stating that Han Chinese settlers would not have been able to survive the harsh conditions in Taiwan without opium, and concluded that the government was on the right path to eventual eradication.

“This time, special licenses will only be given to 25,000 more people, which is just 0.5 percent of the population,” he writes. “It isn’t a big deal, why has it caused so much debate?”

Lien was quickly ostracized by the Taiwanese elite, leading to the General History of Taiwan (台灣通史) author’s eventual departure for China. He never returned.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the