Taiwan in Time: Jan. 2 to Jan. 8

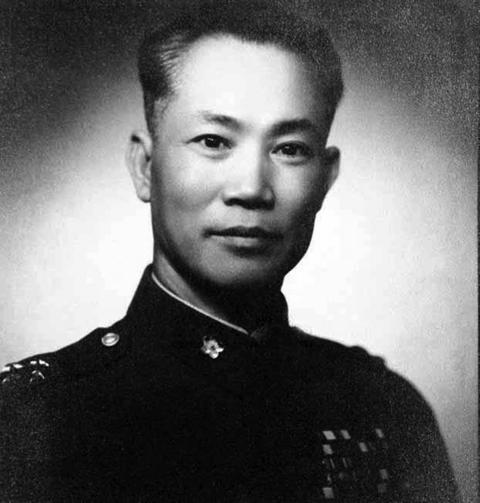

It was a total surprise for Chen Cheng (陳誠) when he received a telegram from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) on Dec. 28, 1948, informing him that he was to become Taiwan Provincial Governor as soon as possible.

Chen had been in Taiwan for nearly three months by then, albeit for the purpose of recuperating from stomach surgery after resigning his many military posts, which included First Chief of the General Staff of the Republic of China Armed Forces. On Nov. 12, Chiang sent him a telegram, telling him to focus on his health and not worry about the deteriorating situation in China.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chen, who was a military man and not a politician, wrote in his memoir that Chiang never asked for his opinion and had not issued a formal order. Chen preferred that Wei Dao-ming (魏道明) keep the position, but Chiang sent him several telegrams, the last one on Jan. 3, 1949 stating “Why have you not assumed your position yet? If you continue to delay, it will only bring trouble and our overall plan will fail.”

Chen had no choice but to report to his post on Jan. 5.

It was a momentous task, as Chen not only had to govern Taiwan and keep it stable as a future base for the KMT to reclaim China, he also had to deal with the massive influx of people from China as well as handle and help set up the governmental and military institutions that were relocating to Taiwan. Furthermore, he acknowledged that the Taiwanese people distrusted the government due to the events of the 228 Incident in 1947.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In a collection of correspondence between Chen and Chiang, it appears that Chen tried to resign several times, citing health issues and his inability to handle the task. But all his requests were denied.

Despite his reluctance, Chen was quite productive during his one year as governor.

To appeal to the peasants in part to prevent them from turning to communism, Chen issued the “375 rent reduction” plan where tenant farmers were not to pay more than 37.5 percent of their annual harvest to their landlords. Prior to that, they often had to pay more than half.

Ou Su-ying (歐素英) writes in The Taiwan Provincial Assembly and the Republic of China’s Relocation to Taiwan (台灣省議會與中華民國政府遷台) that “this drew the ire of the Taiwanese elite, but they were powerless in face of Chen, who controlled both the government and the military.” However, this made him popular among farmers and did help stabilize agricultural society, she adds.

Chen also made extensive currency reforms to tackle the massive inflation of the Taiwan Dollar, issuing the New Taiwan Dollar which is still used today. Finally, in August 1949 he started drafting plans for local self-government, which was implemented at the end of 1950 where people were allowed to elect county and city officials.

Probably the most significant action he took was his declaration of martial law on May 19, 1949, which would remain in place for the next 38 years. This was initially done for weeding out Communists among the massive influx of people from China after the fall of Nanjing, and likely the April 6 student protests against police brutality. However, more restrictive measures would be added, including the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例), which originally targeted Communists but was soon used as a means to control and oppress the entire population as the White Terror era came into full swing.

In March 1950, Chen was “forced” into another position as Chiang asked him to succeed Yen Hsi-shan (閻錫山)as premier.

“It’s not that we didn’t have people who could do the job, it’s that nobody wanted to do it, and Chiang eventually sought me out. I did not think I was qualified, but Chiang insisted. We spoke directly and indirectly about this for at least nine times, and in the end he basically ordered me to do it.”

Correspondence shows that he tried to resign several times during his first year on the job, apparently to no avail.

And thus, Chen’s political career continued, whether he was willing or not — even eventually making it to Chiang’s vice president, which he served continuously from 1954 until he finally succumbed to illness in 1965.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

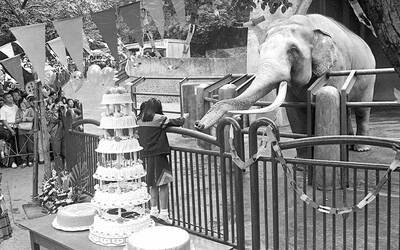

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

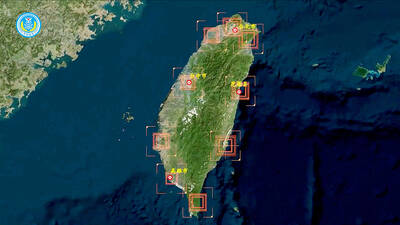

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of