OCT. 31 to NOV. 6

Almost a year had passed since the Wushe Incident (霧社事件), and the survivors of the Sediq tribe that rose up against Japanese rule had been forcefully relocated to Kawanakajima Village after taking another blow when rival Aborigines working with the Japanese attacked them in what is known as the “Second Wushe Incident.”

But the suffering just would not end. On Oct. 15, 1931, Japanese police invited the villagers to Puli under the guise of taking them on a trip to Sun Moon Lake as a reward for their hard work in setting up the village. Instead, they took the men to the precinct and arrested 23 of them who participated in the rebellion. They were never seen again.

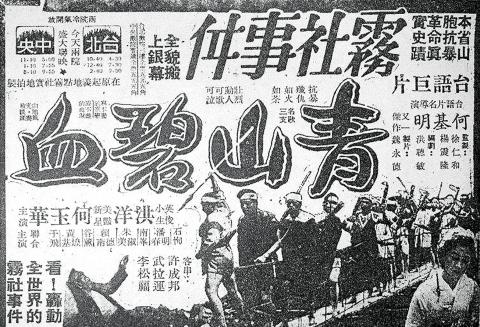

Photo: Lin Liang-che, Taipei Times

This level of brutality makes it surprising to find that just a decade later, 23 Kawanakajima youth volunteered to fight for the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. Only six made it back home.

Last week, Taiwan in Time looked at the direct and indirect causes that led up to the incident, where hundreds of Sediq warriors descended on an athletic meet at the local elementary school and killed 134 Japanese. The Japanese retaliated and quelled the rebellion in two months with about 600 Sediq dead.

This week, we look at the incident’s aftermath and the shift in Japanese colonial policy that led to these young Sediq being willing to die for the empire that mistreated and killed their people.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FROM SAVAGES TO SUBJECTS

Historian Leo Ching writes in the book Becoming Japanese: Colonial Taiwan and the Politics of Identity Formation that the colonial government was under fire after the Wushe Incident. The cause and resolution was “hotly debated in the Japanese Diet, and criticism of the colonial government was voiced both from within Japan and abroad,” Ching writes.

As a result, the government turned from exploitation and suppression to “incorporation and assimilation,” as the Japanese no longer saw the Aborigines as the “savage heathen waiting to be civilized through colonial benevolence, but were now imperialized subjects assimilated into the Japanese polity through the expressions of their loyalty to the Emperor.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This does not mean oppressive policies and labor exploitation ceased, Ching adds, as it was simply a new directive. By 1935, the Aborigines were no longer called “savages,” but takasagozoku, with takasago being an archaic Japanese name for Taiwan and zoku referring to ethnicity.

Meanwhile, the Sediq decided not to talk about the Wushe Incident again after the fake trip incident for fear of further retribution. Dakis Pawan, who was born in Kawanakajima, writes in his book The Truth Behind the Sediq and the Wushe Incident (又見真相: 賽德克族與霧社事件) that whenever people of his father’s generation asked the elders anything about the incident, they would be reprimanded.

BECOMING JAPANESE

During the early days of Kawanakajima village, the Japanese closely monitored the Sediq, calling roll every morning and evening and banning all traditional activities as they sought to transform the tribe into a “modern and civilized” rice farming community. They organized the young people into working groups and taught them how to farm, sell their crops and speak Japanese.

It was not long before Kawanakajima was named an “exemplary Aboriginal community,” an “advanced tribe” that other Aboriginals should aspire toward. Dakis Pawan writes that many of these youth group members recall fondly the experience and held a high opinion toward Japan. They also frequently praised the “Japanese spirit.”

Dakis Pawan personally knew two former soldiers from his tribe who maintained that they were proud to fight for the emperor.

“It is evident that Japanese brainwashing had succeeded … and I never heard anything about them being forced to enlist,” he writes.

But was this “brainwashing” simply achieved by re-education? Ching writes that it is just part of the picture. “Positioned at the bottom of the colonial hierarchy and deprived of any political and economic possibilities, becoming ‘Japanese soldiers’ was perhaps the only avenue to perceived equality and agency.”

Waris Piho, a Sediq soldier, says he fought to “remove the disgrace that has been attached to the Wushe Incident. By enlisting, I would achieve the same honor as the Japanese.”

After the Nationalist takeover, the incident was lauded as a shining example of resistance against Japanese rule — but the fear of retribution remained in the hearts of tribal elders well into modern times. When Dakis Pawan started researching his tribe’s history in 1990 and spoke to a survivor about the incident, the old man shuddered and said, “Is it okay to talk about this now?”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

One of the most important gripes that Taiwanese have about the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is that it has failed to deliver concretely on higher wages, housing prices and other bread-and-butter issues. The parallel complaint is that the DPP cares only about glamor issues, such as removing markers of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) colonialism by renaming them, or what the KMT codes as “de-Sinification.” Once again, as a critical election looms, the DPP is presenting evidence for that charge. The KMT was quick to jump on the recent proposal of the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) to rename roads that symbolize

On the evening of June 1, Control Yuan Secretary-General Lee Chun-yi (李俊俋) apologized and resigned in disgrace. His crime was instructing his driver to use a Control Yuan vehicle to transport his dog to a pet grooming salon. The Control Yuan is the government branch that investigates, audits and impeaches government officials for, among other things, misuse of government funds, so his misuse of a government vehicle was highly inappropriate. If this story were told to anyone living in the golden era of swaggering gangsters, flashy nouveau riche businessmen, and corrupt “black gold” politics of the 1980s and 1990s, they would have laughed.

It was just before 6am on a sunny November morning and I could hardly contain my excitement as I arrived at the wharf where I would catch the boat to one of Penghu’s most difficult-to-access islands, a trip that had been on my list for nearly a decade. Little did I know, my dream would soon be crushed. Unsure about which boat was heading to Huayu (花嶼), I found someone who appeared to be a local and asked if this was the right place to wait. “Oh, the boat to Huayu’s been canceled today,” she told me. I couldn’t believe my ears. Surely,

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she