This 10th edition of the Taipei Biennial, Taiwan’s top international exhibition for contemporary art, celebrates both a milestone and a watershed. It is 20 years since the Biennial boldly set out to become an important international exhibition for art. Until 1996, it existed as a sort of competition for local artists, growing out of a periodic exhibition series ‘Contemporary Art trends in the R.O.C.’ begun in 1984. It is now one of the longest-running international biennials in Asia, and has hosted star curators from Europe, the US and Japan, including Nanjo Fumio, Jerome Sans and Nicolas Bourriaud.

Hitting the 20 year mark is the Taipei Biennial’s milestone, but its watershed is adapting to a new and smaller role in the globalized art world.

When the Taipei Biennial transformed into an international biennial in 1998, it was near the front of a massive wave. It became one of several dozen international biennials, joining the ranks of Venice, Sao Paolo and the old guard of the century-old biennial movement. But in the two decades since, biennials have mushroomed. They were seen by governments as vehicles for “city marketing” and “soft power,” and there are now more than 150 of them worldwide.

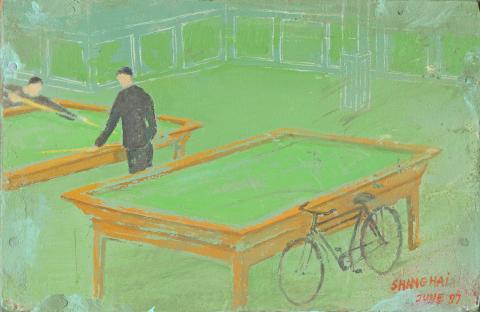

Photo courtesy of tfam

Though Taipei remains an important exhibition in Asia, it has been superseded by the big-budget South Korean biennials in Gwangju and Busan as well as gala arts events in regional financial centers, such as the Shanghai and Singapore Biennials and the Art Basel Hong Kong art fair.

So this tenth edition of the Taipei Biennial, currently on view at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, involves a reassessment of what the museum’s director Lin Ping (林平) called, “the unique and changing role of the Taipei Biennial in the global profusion of biennial exhibitions.”

The exhibition is curated by French academic Corinne Diserens, who is currently director of the art academy Ecole de Recherche Graphique in Brussels, Belgium.

Photo courtesy of tfam

Diserens has invited the largest number of Taiwanese artists — more than 34 out of around 76 total artists — of any Taipei Biennial since the exhibition became international. In addition to Taiwanese visual artists displaying in the galleries, many more local academics, filmmakers and stage performers will be involved in a five-month program of talks, performances and screenings that will continue until January.

At the exhibition opening, Diserens admitted she originally knew little about Taiwanese artists, most of whom were chosen through an open call for projects earlier this year, and only visited Taipei three times to prepare the show.

By fulfilling the role of a local showcase, the Taipei Biennial is in some ways returning to its roots. Both organizers at the museum and Diserens have recognized that in this globalized art economy, not every biennial can compete as a top tier showcase. So then for a second tier biennial like Taipei, the choice is to become a touring exhibition of the latest star artists (if you have the budget, as they do in South Korea), a launching pad for local artists, or some combination of the two.

Photo courtesy of tfam

For the exhibition theme, Diserens, who is a product of France’s socially radical “May 1968” generation, has chosen “Gestures and archives of the present, genealogies of the future.” If this sounds extremely dry and academic, be forewarned — it is.

The first gallery opens with pallets of shrinkwrapped boxes, containing free magazines called 39 Strike Objects by French artist Jean-Luc Moulene. This is potentially a good way to weed out all the viewers who are not interested in the marginalia of post-World War II French labor movements, which is most of us.

If you grab a magazine and flip through, you’ll find photographs of manufactured goods that were the subject of various strikes (mostly in France), along with short monographs about these cigarette packs, frying pans, ball bearings and so on and the various circumstances in which factory workers stopped producing them.

Photo courtesy of Art Sonje Center and the Taipei Biennial

One of these objects, a suit produced of a type of French-invented super fiber whose patent was sold to overseas buyers in the 1980s, has been adopted as the biennial’s key visual. You will need to wade through a lot of fine print to figure that out. The photograph itself is of an empty suit, and if you interpret that image some other way — like perhaps as a world from which all the people have been erased — that is also not a bad measure of the tone here.

But within Diserens frame, Moulene’s short catalog represents a type of mini-archive that is a major object of fascination. She is also fascinated with bureaucracy and institutionalism. She makes an adequate case for why these topics are important, but largely fails to make them interesting.

As one walks through the exhibition halls, one will find a variety of mini-archives. There’s a gallery of framed book pages, all of which mention opium but come from works by different authors. It is a work called Inhale by Iranian artists Nasrin Tabatabai and Babak Afrassiabi.

Photos courtesy of tfam

There is a film, A Tendency to Forget (2015) by Angela Ferreira, about two Portuguese anthropologists who ostensibly did some sort of seminal research in Mozambique in the 1950s.

There are photo essays on Angola five years after civil war by Jo Ratcliffe, the lives of black South Africans under apartheid by Santu Mofokeng and natural disaster sites in Taiwan by Lee Hsu-pin (李旭彬).

With the exception of a couple of really sublime Mofokeng images, these photos and videos offer the most mediocre kind of documentation. There is neither aesthetic presentation, communication of any sort of sensible narrative nor much sense of context. I’m a firm believer that good art should inspire one to care why one is looking at it, but here one wanders through random collections that perhaps represent the uncatalogued fancies of someone else’s mind.

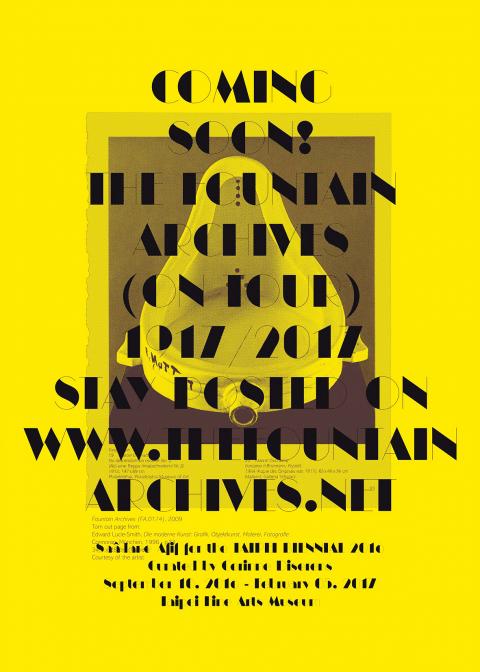

The failure of these mini-archives is perhaps best embodied in The Fountain Archive, which is at first a seemingly curious collection by artist Saadane Afif of more than 800 pages from books and magazines containing pictures of Marcel Duchamp’s groundbreaking artwork Fountain, a prefabricated urinal posed as a “readymade” sculpture in 1917.

Afif’s work is clever, but after a glance, there is nothing more to get. His archive is not historical in any way. He does not analyze any particular data about these pages, though information like publication date, publishing location, photographic source, or keywords could potentially be telling. It’s a collection that is mostly just random, or worse, collected out of convenience. It is a scrapbooker’s type of fascination, and it disappoints precisely because it poses larger questions and then fails to pursue them.

Despite these failings, Diserens has done a few good things. Her reinvestment in the local art community is welcome, and its five-month program of talks, performances and events seems both innovative and promising. But as for what one encounters in the galleries — the ostensibly central element of an exhibition of contemporary art — this is the probably worst Taipei Biennial in 20 years.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,