Aesthetically speaking, Le Moulin (日曜日式散步者) is a beautiful, unique and creatively executed piece that captures the spirit of the surrealist French-influenced, Japanese-educated Taiwanese poets of the 1930s, an experimental documentary that meshes tastefully recreated scenes, evocative sequences, carefully selected details, poetry readings, historical photos and footage and text to create a multifaceted feature film that is almost like an extensive, epic ballad.

The film focuses on the Le Moulin Poetry Society, founded in 1935 by Yang Chih-chang (楊熾昌), Lee Chang-juei (李張瑞) and Lin Hsiu-er (林修二), who were proponents of French surrealism but wrote in Japanese, as many of the Taiwanese elite did at the time. Le Moulin only lasted a year, but the story follows the writers’ literary endeavors and correspondence up to the end of Japanese rule and the demise of their art form during the White Terror era.

The film’s driving narrative is the recreated scenes of these literary compatriots interacting with each other, carrying a loose focus on Lin as it delves into his home life and marriage. Few faces are shown, just hands, movement and voices, which is an inventive way to represent a past era. Notable publications are cleverly inserted into recreated scenes, and there’s also great deal of poetry, whether in text or through readings. There’s also plenty of historical found footage, providing background of the conflict on cultural, political and economic fronts during turbulent times.

Photo courtesy of atmovies.com

Here’s the problem though: there’s a reason why poetry is often short and sweet. The concept for the film is refreshing — but no movie without a comprehensible storyline, tension or memorable characters should be 162 minutes long. The first hour or so was enjoyable — and it should have ended there, but the film continued to mosey on at a snail-like pace without an end in sight.

There is ground to cover, as the story spans several decades. But like any film, it can be condensed, and probably should have been. There is too much crammed in here, as the “story” is bogged down by poetic and picturesque stylings that are delightful at first but become tiresome after a while. Even the ending simply wouldn’t end after the plot had already concluded, with atmospheric scene upon atmospheric scene leading to suffocation.

Perhaps it is not a surprise that director Huang Ya-li (黃亞歷), a young experimental filmmaker, had only produced short films before Le Moulin. His 2008 work The Pursuit of What Was (物的追尋), lasted only 22 minutes, and the 2010 The Unnamed (代以名之的事物) ran for an even shorter 11 minutes. The difficulty in transition from shorts to feature is obvious here for the aforementioned reasons.

Huang “discovered” the poetry society in Lin’s thesis while doing research on Taiwanese surrealism. After half a year of research and field study, he decided to put the film together.

Alas, this is the type of film that infallibly garners rave reviews at the international festival circuits, promoting local arthouse filmmakers to churn out more uncompromising films like Le Moulin. There is definitely an audience for this type of film, but with such a promising idea — especially one depicting such a little known slice of Taiwanese history — one would wonder if it could have been edited to be a bit more suitable for the general public. But then, would that be compromising the director’s artistic vision? After all, it’s not meant to be a mainstream film, and maybe that’s why high art and pop culture don’t often mix.

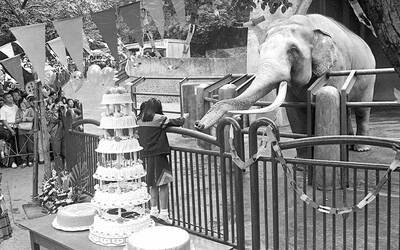

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

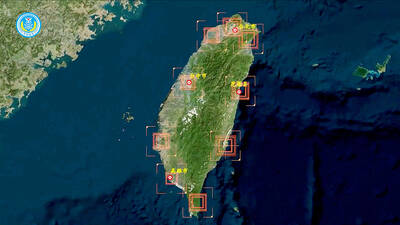

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of