Speeches by Taiwanese undergraduates gave UK-based researcher Heath Rose his first hint that he’d made a mistake attending the International Conference on Business and Information in Sapporo, Japan.

Typically, undergrads don’t present at the same conferences as professors. But Rose says the 2012 event, which was organized by Taiwan-based International Business Academics Consortium (iBAC, 國際商學策進會), seemed full of Taiwanese students reading their speeches and uninterested in discussing their research.

Rose says iBAC didn’t inform presenters they had only 10 minutes — a scheme that can significantly boost the number of participants.

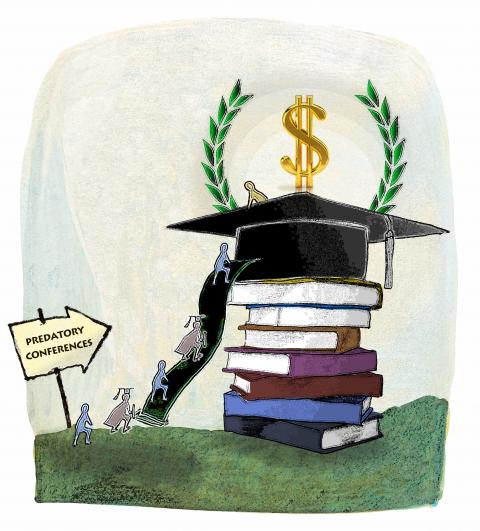

Illustration: Angela Chen

“I definitely left that conference feeling that I wouldn’t present at it ever again and not be involved in the organization again,” Rose says by e-mail. (Full disclosure, the author worked with Rose at a Japanese university more than a decade ago.)

PREDaTORY CONFERENCES 101

Rose inadvertently attended what’s known in the academic community as a predatory conference. These faux conferences, which prey on the need for academics to present and publish their research, make an exorbitant amount of money for their organizers for very little professional gain and sometimes to the detriment of the academics’ career.

Taiwan’s post-graduate education is run on a points system. The greater number of conferences attended by associate and assistant professors, the more points they will receive, boosting their chances of promotion.

Graduate students benefit from predatory conferences because attending one fulfills a major requirement for graduation — and the government offers students generous subsidies to attend them (NT$40,000 — US$1,265 — for a five-day trip to Japan is not uncommon). Additionally, as Rose learned in 2012, pretty much anyone who signs on can present a paper.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

Jeffrey Beall, a librarian and associate professor at the University of Colorado, Denver, devotes his Scholarly Open Access blog (scholarlyoa.com) to the issue of predatory publishers. Beall says in an e-mail that predatory conferences remove “merit, selectivity and peer review from the system of academic evaluation, and [replace them] with a product that pretty much anyone can purchase.”

iBAC is one of two Taiwan-based groups targeting researchers with predatory conferences. The other is the Higher Education Forum (HEF). iBAC and HEF charge up to US$450 to present at their conferences. They then funnel conference papers to blacklisted for-profit publishers.

iBAC’s Web page says that it has been a “non-profit organization for the international academic community since 2009.” However, iBAC’s name began appearing in 2007 on Web sites as conference cohost.

iBAC president Fang Wen-chang (方文昌), a professor at National Taipei University, didn’t respond to repeated requests to explain iBAC’s activities and how it uses conference fees.

HEF describes itself as “a professional conference organizing company” on its Facebook page. Kate Lee (李亞勻), a contact person given to the Taipei Times, didn’t respond to e-mail requests about how the company uses the proceeds of their conferences.

NONSENSICAL PAPERS

Authentic academic conferences use a system called peer review to evaluate proposals. Other university instructors read them and decide if they are worth accepting.

To test iBAC and HEF’s peer review systems I submitted fake proposals using SCIgen, an online tool developed by graduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to test conference standards. I then created grammatically correct, but nonsensical, papers.

Using the pseudonym Dr Sandor Edelstein, and listing him as a professor at the non-existent Japanese university Fukuoka Educational College of Knowledge (FECK), I submitted two fake papers each to iBAC and HEF conferences.

One paper is called A Novel Approach for the Emulation of Cache Coherence. The paper begins: “The hardware and architecture method to the Turing machine is defined not only by the visualization of link-level acknowledgments, but also by the unfortunate need for the producer-consumer problem.”

Another paper, Visualizing Cache Coherence Using Extensible Models, begins: “Thin clients must work. After years of important research into kernels, we confirm the theoretical unification of systems and consistent hashing, which embodies the confusing principles of networking.”

The other papers are equally incoherent. All four phony papers submitted by a pretend professor from an imaginary institution received acceptance. iBAC and HEF claim at least two reviewers evaluate all proposals. But both organizations failed to answer why they accepted the fake papers.

SWIMMING IN MONEY

Despite the absence of quality control — or perhaps because of it — iBAC conferences are well attended. About 300 people from 16 countries attended an event at Tokyo’s Waseda University. iBAC’s subsidiary, International Academy Institute, held four conferences in four classrooms from July 22 to July 24 of last year.

Assuming everyone paid the early registration fee of US$400, the event generated approximately US$120,000 in revenue.

Costs appear to have been minimal. According to Hajime Tozaki, a Professor at Waseda University and the conference local chair, Waseda provided the classrooms for free. He says he didn’t receive any compensation for delivering the keynote speech or being the local chair of the conference.

No one from iBAC would answer how it uses conference revenues. In an e-mail, an iBAC staff member, referring to himself only as James, said “iBAC is a registered organization in Taiwan. We legitimately pay taxes and organize conference [sic] in Asia.”

HEF charges US$400 to present at its conferences and US$250 to attend. HEF’s Web sites also provide links to travel companies offering special tour packages for Taiwanese participants. An HEF spokesperson, who declined to state their name, wouldn’t say if it profited from these packages.

Keith Edwards, an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and a member of the iBAC Advisory Board (removed from their Web site after questions for this story were e-mailed), says that government pressure might be behind the increase in these kinds of conferences.

“I think that there’s some new government pressure on universities and faculty in Taiwan to engage in organizing conferences as a way of showing value. This may be driving some of the new conferences, but that’s just my opinion,” Edwards says.

It’s difficult to determine how many conferences the two groups organize. iBAC staff member James didn’t respond after replying with questions of his own to see if I was a “qualified academic researcher.”

iBAC’s Web site lists only a handful of its conferences. An Internet search found 28 conferences at 10 events scheduled by iBAC and its subsidiaries and partners for last year. More than half were located in Japan with the others held around Asia.

A HEF spokesperson said by e-mail that the company organized 20 conferences across Asia last year. Yet an Internet search found 59 conferences scheduled, with at least 30 held in Japan and the rest divided among eight other Asian countries.

iBAC and HEF also maintain opaque relationships to other conference organizers. iBAC’s subsidiary, International Academy Institute, organizes conferences in Japan and other Asian countries.

iBAC also cohosts events with the Academy of Taiwan Information Systems Research and the Knowledge Association of Taiwan. Fang served as president for both groups in the past.

A fourth group, called the Social Science Society, sponsors iBAC conferences and its three-member advisory board (two from Japan and one from Thailand) also sit on iBAC’s advisory board. iBAC declined to respond to questions about their relationship with these organizations.

HEF also has partners that don’t appear on their Web site. Attendees paying their conference fees by bank transfer sometimes send the money to the Asia-Pacific Educational Research Association Inc’s Mega International Commercial Bank account in Hong Kong.

HEF failed to answer questions about their relationship, but Web sites show Asia-Pacific Educational Research Association shares the same Fuxing South Road (復興南路) address as HEF and also organizes conferences.

iBAC and HEF also obscure who is in charge. Until the end of September last year, iBAC’s Web site listed the names and photographs of a six member “Advisory Board,” four from Japan and one each from Thailand and the US.

After I contacted two Japanese members of the board, the page was suddenly removed and replaced with the names of the board of directors. However the directors’ names appear only in Chinese and lack titles and photographs.

PREDATORY PUBLISHERS

HEF’s Web site doesn’t list the names of any individuals involved with the company. Even acceptance letters sent to presenters contain only an indecipherable signature and use a .gmail account. The unnamed HEF spokesperson declined to provide the name of the company owner.

iBAC and HEF also funnel conference papers to predatory journals. iBAC recommends papers to journals published by Science Publications, an iBAC conference sponsor. The company charges authors a publication fee ranging between US$350 and US$525.

Science Publications is blacklisted on Beall’s list of questionable publishers that academics should avoid.

HEF directs papers to six publishers on Beall’s blacklist. When asked about HEF’s relationship with them a spokesperson replied by e-mail that “it might be our oversight that some of our cooperated parties are not qualified. We are now doing annual review of these journals/publishers, based on their publications this year. We shall decide if the cooperation should be continued.”

Beall warns that publishing in journals on his blacklist could be “potentially damaging to the attendees, whose reputations could be hurt by publishing their work in low quality, predatory journals.”

iBAC also hurts reputations by falsely claiming researchers as conference organizers.

Despite Rose’s unsatisfactory experience in 2012, between 2013 and this year iBAC Web sites listed his name as a conference committee member at least five times without his knowledge.

“This organization has never approached me to ask me to be part of this committee,” Rose says, “and I’ve certainly not given my consent to be listed.”

Three university professors listed on the Tokyo conference Web site as members of the “International Committee” said by e-mail that they weren’t aware of the conference and hadn’t given permission for their names to be used.

The Canadian university of one of the wrongly listed instructors e-mailed iBAC on June 23 of last year demanding that their instructor and school’s name be removed immediately. The instructor’s name remained listed as of last week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has