Taiwan in Time: Aug. 1 to Aug. 7

At the end of World War II, the Taiwanese in Beijing got together and celebrated the defeat of Japan, which had colonized Taiwan in 1895 and conquered much of East Asia in the 1930s and 1940s.

Beijing fell to the Japanese in October 1937, and as Japanese citizens, many Taiwanese traveled there to work. Official Japanese records show that between late 1937 and early 1944, the Taiwanese population increased from 37 to 548. The majority of them worked for the Japanese as minor officials and translators or as Japanese language teachers in local universities.

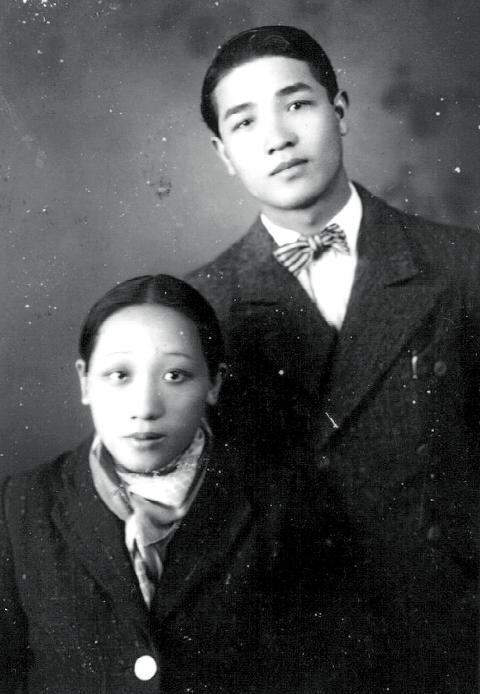

Photo courtesy of Chung Li-ho Literary Memorial Museum

After the war, those Chinese officials that ranked higher than county commissioner under the Japanese were deemed traitors and punished. Most Taiwanese did not qualify, but many lost their jobs and were seen as traitors by the Chinese anyway — finding it necessary to hide their Taiwanese identity.

Pingtung native Chung Li-ho (鍾理和) was deeply disturbed by this treatment, noting that he had happily celebrated when the Japanese surrendered. After no Chinese official showed up at the Taiwanese in Beijing Association’s formal celebration, Chung wrote the short story, The Sorrow of the White Sweet Potato (白番薯的悲哀).

“They were cast aside by the motherland,” he writes. “They wanted encouragement, comfort, warmth, the gratitude of a long-awaited reunion — but there was nothing. The white sweet potatoes walked out of the celebration feeling empty, disappointed and miserable.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

He says that they were “excluded from the motherland’s glory” because of history, because they were once citizens of the enemy.

“Beijing is large,” he writes. “Its greatness and humility can embrace everything within — but if someone finds out that you’re Taiwanese, unfortunately, that equals a death sentence. Then, you will start feeling that Beijing is cramped — so cramped that it cannot hide you anymore.”

Chung swore not to return to Taiwan when he first arrived in China eight years previously, but in March 1946, Chung, his pregnant wife and their son boarded a refugee boat to Keelung, arriving in his family home in Meinong District (美濃) in today’s Kaohsiung later that year.

Chung and his literary contemporary Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) both wrote about the identity crisis of Taiwanese during World War II, being distrusted by the Chinese in the “motherland” and discriminated against by the Japanese at home. But while Wu sought a new life in China after being fed up with discrimination, Chung fled Taiwan in the name of love.

Born to a wealthy family, Chung was always fascinated with China, which he calls the yuanxiang (原鄉, original or old country), through listening to his father talk about his travels after business trips to China. When Chung’s brother returned from a trip to China, they listened to records and marveled at scenic photographs. He writes in his novel, From the Old Country (原鄉人) about his experiences with people from the old country, starting from the private Chinese-language school he attended to various peddlers he would meet, developing a generally positive impression.

“I’m not a patriot, but the blood of one from the old country will not stop boiling until he returns to the old country,” Chung proclaims in the novel.

After graduating from a Japanese school, Chung spent a year and a half learning Chinese, before later finding work on his father’s farm in Meinong. There, he fell in love with farm worker Chung Tai-mei (鍾台妹), but their union was met with disapproval because they shared the same surname. Chung severed relations with his family and fled to Shenyang in 1938, which was then under Japanese control, and came back to elope with his lover in 1940.

“Unless you’re very naive, you would never expect your father to risk his reputation to hold such a wedding for his son,” he writes in the novel Lishan Farm (笠山農場), which is based on this incident. “Maybe young people see glory and greatness in being a revolutionary, but no father would want his son to start a revolution.”

Chung asserts his unwavering belief in fighting one’s fate in two other novellas. In Weak Breath (游絲), he tells the story of a woman whose father tries to force her into an arranged marriage, detailing her struggle between accepting fate or fighting for what she really wants. And in Silver Grass (薄芒) he details the tragic results and sacrifices people make when they obey traditional values over their own desires.

“People are willing to accept this cup of bitter wine, tears streaming down their face, saying that this is fate,” he writes.

Indeed, Chung was a true idealist, choosing to live in poverty over working for the Japanese, writes literature professor Chen Chao-chen (陳兆珍) in her book, A study of Chung Li-ho’s Thought and Work (鍾理和思想及其小說研究). And despite being mostly educated in Japanese, he insisted on writing in Chinese. It is not hard to imagine his dismay when he was forced to return to his homeland where he still “had memories of past sorrow.”

Chung writes that he developed tuberculosis during his 20-day journey on the refugee boat with not enough to eat or sleep.

He worked as a Chinese teacher for a while, but quit due to his illness. The final 10 years of his life would be his most prolific period as an author, but it was not easy. Living in poverty after exhausting the family’s resources, his older son developed a disability due to illness and his younger son died. He was still looked down upon by the community due to the taboo he violated, and his brother and his closest childhood friend were executed during the White Terror era. One bright spot was Lishan Farm winning a national literary award in 1956.

Legend has it that Chung kept writing despite his illness, and died after coughing blood onto a manuscript, earning him the moniker “The Writer who Lies in a Pool of Blood (倒在血泊中的筆耕者).”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the