Taiwan in Time: June 27 to July 2

Over the years, the term “Orphans of Asia” (亞細亞的孤兒) has been used to describe a number of things, including Taiwan’s political isolation and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops stranded in Thailand and Myanmar after they lost the civil war.

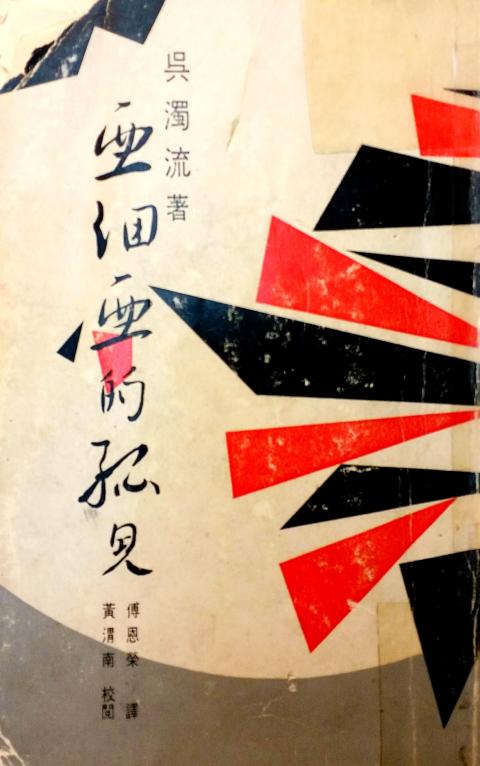

But originally, when Taiwanese author Wu Cho-liu (吳濁流) first used the term as the title of his debut novel, written in Japanese during World War II, it referred to Han Chinese living in Taiwan under Japanese rule because they neither truly belonged to Japan or China.

Photo: Tsai Meng-shang, Taipei Times

The novel follows Taiwanese intellectual Hu Tai-ming (胡太明), who, after leaving for China after being mistreated in Taiwan by the Japanese, found himself also the subject of discrimination by the Chinese, who distrusted him and saw him as a Japanese traitor.

“Hu is a victim of this twisted chapter of history,” Wu wrote in the introduction to the Chinese edition, adding that he wrote the book for both future Japanese and Taiwanese to remember that period.

It was quite a daring move for Wu to write the novel while Taiwan was still a colony of Japan, especially during war time when imperialist fervor was at a peak and absolute loyalty was required. He writes that he had to hide his manuscripts or disperse them in various places in the countryside because he would have been charged with treason if they would have been found.

Photo: Wang Chin-yi, Taipei Times

“Nobody would dare use that kind of historical backdrop in a novel in those days, much less depict the true reality of those times without any hesitation or restraint,” Wu wrote. “History often repeats itself. But before it repeats itself again, we need to look at the facts so we can learn our lessons.”

Wu details in the introduction the immediacy in finishing the novel as Japan neared defeat in 1945. The Americans had captured Manila by then, and there was much speculation among intellectuals on where they would land next, and how the Japanese would react in case they chose Taiwan.

“The fear in my heart was completely suppressed by my urgency to finish the novel,” he wrote. “The airstrikes were becoming more frequent, and you couldn’t predict when a mishap would happen. Thinking back, I’m glad I had that kind of drive. If I were to write it today, I would not be able to convey the same sense of reality.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Born on June 28, 1900 and living to be 76 years old, Wu spent about half of his life under the Japanese and half under the KMT. His novels have often been studied due to their detailed descriptions of Taiwanese society during and after Japanese rule.

Wu was raised in a prominent Hakka family in the Hsinchu area, and received both a Chinese and Japanese education.

His life experiences closely mirror the ideas in Orphans of Asia. Wu worked as a teacher after college, but soon became monitored by police for his criticism of the education system and also because he read magazines published by Taiwanese students in Japan, such as Taiwan Youth (台灣青年), which often contained writing that authorities considered subversive.

Because of this, Wu was transferred to one of the most remote areas for teachers in the Hsinchu area. He describes this as a time where he had “no dreams and no ideals,” but it was also one of the happiest of his life.

Wu did not start writing stories until he was about 36 years old. In 1937, he left the countryside and started teaching at a larger school, where discrimination against Taiwanese staff was rampant and he was forced to rethink his position. The Japanese also invaded China around this time, and the authorities started their aggressive “Japanization” process of the Taiwanese people.

Finally, after a conflict with Japanese staff at the school, he quit his job and headed to China in 1941 — a place where many Han Chinese in Taiwan at the time saw as their motherland.

Wu landed in Nanjing, which was then ruled by the Japanese collaborationist government headed by Wang Jingwei (汪精衛). He did not speak Mandarin at first, and soon found that due to anti-Japanese sentiment in China, the people there often saw Taiwanese as Japanese spies.

“Taiwanese are like orphans who lost their parents,” he wrote in his autobiography, The Fig Tree (無花果). After seeing that the situation was no better in China, Wu returned to Taiwan and started working on Orphans of Asia.

After the Japanese left and the KMT took over, Wu was finally able to publish the novel, which was translated into Chinese in 1959.

But here is the irony of Wu’s literary career: The Fig Tree, published in 1970, was immediately banned by the KMT due to its description of the 228 Incident, and did not reappear until it was republished in 1988.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual