Taiwan in Time: June 20 to June 26

Here’s how the story goes: In late June of 1895, Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) swore a blood oath with Tainan’s elite, vowing to defend Taiwan against the advancing Japanese troops to the death and to continue fighting as long as there was one bit of territory left.

He then assumed command of the one-month-old Republic of Formosa (台灣民主國),which carried on for four more months until Qing Dynasty China ceded Taiwan and Penghu to Japan in the Treaty of Shimonoseki. But the Japanese met unexpected local resistance as they closed in on Tainan. Liu then abandoned ship and fled to China on Oct. 19, two days before the enemy even arrived.

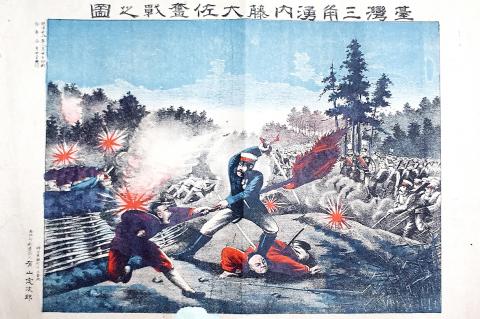

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

So much for the oath, if it even took place at all.

It is generally agreed that Liu, who was originally operating in today’s Kaohsiung, assumed leadership of the Republic of Formosa after the Japanese captured its capital of Taipei a few weeks earlier. By then, president Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧) and vice president Chiu Feng-jia (丘逢甲) had both fled to China. But historians seem to be in dispute about what exactly happened.

Some say that the elite officially swore Liu in as president and extended the life of the republic, while others say that the republic met its end when Taipei fell and Liu simply assumed command of the remaining resistance while refusing to be president.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

And there are also those who say that Liu, facing a lack of resources, was not even particularly enthusiastic in continuing what seemed to be a lost cause — especially after a failed attempt at securing arms and supplies from China.

Academia Historica director and historian Wu Mi-cha (吳密察) writes in the study Liu Yung-fu in the Yiwei Battle (乙未之役中的劉永福) that it was the effort of civilian militias in Taoyuan, Hsinchu and Miaoli as well as troops in central Taiwan organized by a local official that Liu was able to hold out until October. Wu adds that Liu Yung-fu was even reluctant to send reinforcement troops northward.

Historian Tsai Cheng-hao (蔡承豪) writes in A Tainan Pastor Becomes a Messenger of Peace (台南牧師成為和平使者) that Liu’s army remained mostly idle in the south, and that he barely assisted in the efforts up north. Tsai writes that he was banking on foreign or Chinese aid, which never came.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After winning the decisive Battle of Baguashan (八卦山戰役) in Changhua, the Japanese regrouped and planned their invasion of Tainan. Instead of taking on the enemy, Liu made several attempts to sue for peace, but to no avail before fleeing.

Nevertheless, he was hailed as a national hero due to the prevailing anti-Japanese sentiment in China and in Taiwan after Japan’s defeat in 1945.

A NEW REPUBLIC

Liu had earlier risen to fame in China as the leader of the legendary Black Flag Army that resisted the French in Vietnam during the Sino-French war of 1884. He was deployed to Taiwan by the Qing in 1894 during the First Sino-Japanese war. The Qing lost that war, which resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki on April 17, 1895.

On May 25 that year, the Qing officials and the Taiwanese elite established the Republic of Formosa (台灣民主國), with former provincial governor Tang Ching-sung as president. The capital was at Taipei, with a flag featuring a yellow tiger against a blue background.

Several sources, including historian Chen Yi-hung (陳怡宏), say that part of the motivation was that by disassociating from the Qing Empire and claiming that Taiwan was merely defending its own territory, it would be in a better position to request foreign aid.

Alas, no help came. Meanwhile the Qing and the Japanese formalized the cession. The Japanese landed in Taiwan on May 29, capturing Keelung on June 3, upon which Tang fled to China, his presidency lasting about 10 days. The troops that he abandoned reportedly turned to terrorizing the people of Taipei.

Vice president Chiu, a native of Taiwan and one of the main architects of the republic, reorganized the troops to defend Taipei, but as the republic’s capital fell, he also fled to China.

Tang, Chiu and Liu all left Taiwan in the face of defeat, but Liu was hailed as an anti-Japanese hero, most likely because he held out until the end. Historian Chen Wen-tien (陳文添) writes in On Liu Yung-fu’s Flight from Taiwan and the Conflict between the British and Japanese (談劉永福棄守臺灣及引發之日英糾紛) that the Japanese commander gave him a chance to leave after his compatriots fled, but Liu declined, stating that he had not received orders from the emperor.

MAKING OF A HERO

But the stories still make him out to be a greater military commander than he likely was. Wang Chia-hung (王嘉弘) writes in his book Literature about the Cession of Taiwan in 1895 (乙未割台文學與文獻) that much of this was due to novels that proliferated in China after the battle, featuring Liu as a brave and loyal military commander who frequently outsmarted the Japanese invaders with clever tactics.

Wang says that these novels were not necessarily well-written, but became bestsellers because they capitalized on the anti-Japanese sentiment in China, a country still licking its wounds from the recent humiliation.

“The content of these novels are preposterous and have no historical basis,” Wang writes. “They greatly exaggerated the Black Flag Army’s accomplishments in Taiwan to achieve the portrayal of Liu Yung-fu as a hero.”

The media also contributed to his image. Chen writes in the book Transformations in 1895 (鉅變1895) that the Qing media “pinned all its hopes on Liu, and until he returned to China, the media was full of ‘imaginary’ reports that depicted how Liu defeated the Japanese.”

How do these stories reconcile the fact that although Liu won battle after battle, Taiwan was still lost to the Japanese?

Chen Chia-chi (陳嘉琪) writes in Liu Yung-fu’s Anti-Japanese Image in Taiwan Historical Legends and Literature (台灣歷史傳說與讀物中的劉永福抗日形象) that several of them end by stating that even though Liu won the war, the Qing were still forced to cede Taiwan to Japan — which simply does not match the historical record.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry