Taiwan in Time: May 16 to May 22

On April 20, 1949, negotiations broke down between the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party, as the People’s Liberation Army continued its offensive, capturing the Nationalist capital of Nanjing three days later and then continuing to push southward.

Chen Cheng (陳誠), who had been sent to govern Taiwan five months before the offensive, was worried that Communists would try to sneak their way into Taiwan amid the mass Nationalist retreat across the Taiwan Strait, writes historian Chen Shih-chang (陳世昌) in his book, Taiwanese History, 70 Years After the War (戰後70年台灣史).

Courtesy of Google

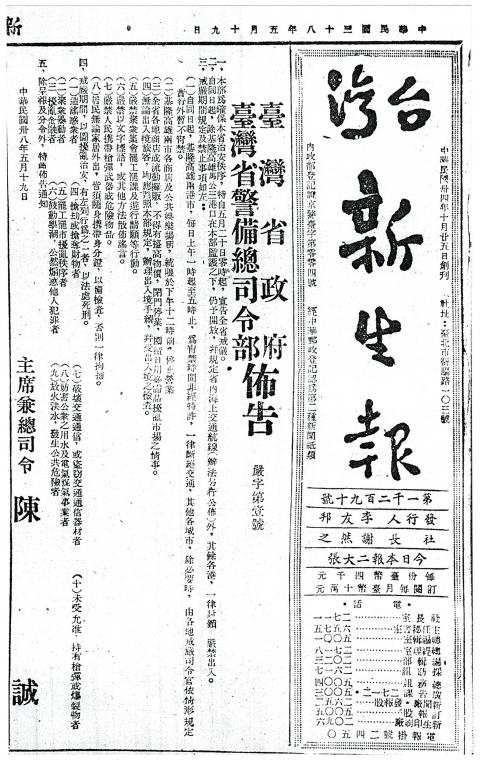

On May 19, Chen Cheng declared martial law, to take effect at midnight the next day.

Chen Shih-chang writes in his memoir that martial law provisions made it easier for him to enact laws to restrict people entering and exiting Taiwan — the main purpose being to weed out possible communists. He was likely also responding to unrest within Taiwan, such as the student protests against police brutality that led to the April 6 Incident when military and police personnel stormed National Taiwan Normal University dorms and arrested about 200 students.

Some dispute the legality of this move, claiming that Chen Cheng had no right to declare martial law as, according to Article 39 of the Republic of China constitution, only the president had the power to do so and it had to be subsequently approved by the Legislative Yuan. Chen Cheng, however, claims in his memoir that he was acting under direct orders from the central government.

Photo: Tsai Chih-ming, Taipei Times

No matter what Chen Cheng’s intentions were, or whether it was legal or not, his declaration would remain in place for the next 38 years and 56 days — one of the longest duration of martial law in the modern era.

The real ramifications were that after the KMT’s full retreat to Taiwan, they would use it to keep Taiwan in a constant state of emergency and, combined with other laws, they exercised authoritarian control over the government and people.

It was the second time martial law had been declared in Taiwan. The first one was issued in 1947 by governor-general Chen Yi (陳儀) the day the 228 Incident broke out, and curfews were imposed in Taipei and Keelung. Chen lifted it the next day, only to declare it again on March 8 as the situation worsened and government troops clashed with civilians. Meanwhile, the commander in Hsinchu made his own declaration on March 4.

Photo: Wu Hsing-hua, Taipei Times

This period was short-lived. On May 16, Wei Dao-ming (魏道明) arrived to replace Chen Yi, and one of his first acts was to lift martial law and stop the government’s qingxiang (清鄉, the countrywide arresting or killing of civilians suspected to have ties to the uprising).

KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) declared martial law in December 1948 as the civil war worsened — but this issuance excluded non-war zones such as Tibet (which the KMT had no control over anyway), Qinghai and Taiwan.

Chen Cheng’s initial declaration closed all ports except for Keelung, Kaohsiung and Makung, established curfews for civilians and businesses, forbade merchants from raising prices or stocking up on goods for personal use and prohibited public gatherings, strikes, protests, bearing arms and “spreading rumors.” All citizens were required to have identification on them at all times, or face arrest.

Later that month, the Punishment of Rebellion Act (懲治叛亂條例) was enacted, which called for automatic death sentences for internal rebels or traitors to the country. The act specified that all trials be carried out by military tribunals regardless of the subject’s identity. Originally aimed towards Communist collaborators, the KMT would later use the act, along with the Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion (動員戡亂時期臨時條款), to suppress freedom of speech, ban opposition parties and arrest suspected independence activists and other dissidents.

Finally, provisions were enacted allowing government screening and censorship of all publications, recordings and performances. Restrictions included defaming government leaders, promoting communism, swaying civilian loyalty toward government and disrupting social security — but in reality the scope was much wider, including sexually-explicit content and even martial arts novels.

With that, all conditions were ripe for the height of the White Terror era.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the