As white fog creeps into our cabin, I feel violent winds shake the small aircraft. When we land at the airstrip in Lanyu (蘭嶼), also known as Orchid Island, I see the ground crew applauding our pilots as if to salute their achievement.

The 20-minute trip from Taitung may have been bumpy, but we were lucky to arrive at all. Locals go out of their way to tell us that we visited the island at the wrong time, as strong winds and heavy rain are common during winter.

Flights and ferries are often canceled; restaurants and food stalls are closed.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

Our hostess Jirina Han (韓秀蓉) is more diplomatic, calling us “the kind of tourists who want a little peace and quiet,” as she greets us in front of her eco-friendly guesthouse.

VOLCANIC ISLAND

Located off Taiwan’s southeastern coast, Lanyu is home to the Tao (達悟) people, Aborigines who are believed to have migrated from the Batanes Islands in the Philippines approximately 800 years ago. They call the volcanic island Pongso no Tao, meaning “island of the people.”

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

We waste no time jumping on a rented scooter, coasting the main road that circles the isle and marveling at the geologic wonders left by volcanic activity.

We encounter spectacular sea caves and arches jutting out of the deep blue waters, where the sight and sound of crashing waves deafen and enthrall. Magnificent lava columns tower above the grass-covered shores, making it perfect for a picnic.

Known by its Han-Chinese name of five-hole cave (五孔洞), this popular geological site on the island’s northern end exudes an eerie, mysterious atmosphere. Devoid of visitors in winter, the colossal connected caverns feel like they belong in a surreal dream, with animal skeletons scattered about and crucifixes erected by local churches. Adding to the unease is a lingering traditional Tao belief regarding the place as a dwelling of anito, or evil spirits.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

The 38km road that rings the island connects Lanyu’s six villages. Most Han inhabitants live in the Yayo (椰油) and Imowrod (紅頭) hamlets on the west side. The harbor, airport, health center and district office are located here, along with the island’s only ATM, gas station and 7-Eleven convenience store.

Another scenic road bisects the island, linking Imowrod and Ivalino (野銀) village on the east side. On a sunny day, the weather station atop the central ridge offers an open view of the sea and a haven of tranquility and solitude guarded by a lone, friendly dog.

It takes one hour to circle Lanyu on a motorbike. But we move at a slow pace, struggling to stay upright amid gale-force winds, which blow in from the Ocean from October to February, while trying to avoid hitting the free-roaming flocks of goats. The Tao regard their livestock, mostly pigs and goats, as a token of wealth, and do not rear them in pens. Consequently, they can be seen everywhere, from rooftops to the edges of cliffs.

Locals tell us that if a driver accidentally kills a goat, the compensation is a minimum NT$8,000. Ownership is easily determined with distinct marks on the animals, and the same system applies to trees in the forest, which are a valued resource for building traditional canoes known as tatala.

WATER ACTIVITIES

Miraculously, we see two sunny days during our visit. We take advantage of the weather to take a dip in a coral pool of calm, turquoise water, located five minutes on foot from our guesthouse. Apparently, it is a playground for local kids. A boy tells us he often visits this “secret spot” to dive and “look for sea snakes.”

Han and her husband Huang Kuang-te (黃光德), nicknamed A-te, also take us on a late-afternoon ocean safari at low tide, when thriving reef wildlife are exposed. A-te even braves the crashing waves to pick for us a handful of carrageenan moss, a type of red algae grown on cliffs. The ocean salad tasted divine, with seawater as its only dressing.

In warmer months, Lanyu’s crystal-clear water and abundant reefs make it a fine spot for scuba diving. During flying fish season, locals will take visitors out fishing at night.

Free divers come here too. While Han is a free-diving enthusiast, A-te resembles an amphibian caught on Han’s underwater camera, which shows him walking effortlessly at the bottom of the sea.

As for us, we were perfectly content to watch the breathtaking sunrise on the coral reef just a few steps away from our room, and later relaxing on the thatched-roof pavilion facing the ocean being mesmerized by the blanketed night sky.

LOST HOME

Despite our idleness, we manage to visit a traditional Tao dwelling. The semi-underground houses were developed over centuries to adapt to the island’s scorching hot summer and windy winter. In the 1960s, most traditional homes were torn down to make way for modern public housing.

Today, the largest cluster of traditional dwellings is located at Ivalino Village, where 17 of the 41 remaining dwellings are still used by tribal elders. Visitors need to take a guided tour (NT$250 per person) to enter and take photographs.

Our guide, an Ivalino native, says he was born and raised in the house which is “cool in summer and warm in winter.” Toilets, showers and other modern-day comforts came later when he moved to the nearby public housing in the 1990s.

WHO IS THE REAL ANITO?

Much has changed and been lost since the Tao first arrived on Lanyu in canoes.

The Tao say anito may no longer be the evil spirits that haunted their ancestors. What is more threatening is the loss of their language, traditional values, beliefs and way of life after decades of repression and assimilation into modern Han-Chinese culture.

One modern-day anito, in particular, stands quietly on the south point of the isle, stowing barrels of nuclear waste shipped from the mainland. The storage facility not only elicits collective fear but strength and determination to fight off the evil spirit.

Winds starts to blow again on the day we leave, planes are again canceled and we end up leaving by ferry. Following Han’s advice, I remember to take my anti-seasickness medicine. As a couple of passengers start retching, I am rocked to sleep, watching towering walls of dark water forming not far from our vessel.

Before I close my eyes, I suddenly remember how Han described the first time she saw hundreds of delicate flying fish surround her boat, gliding and glittering under the silver moonlight.

“Lanyu is an entry into a magical world,” she said.

I concur.

IF YOU GO

Getting there

? Lanyu is accessible by sea or air. Daily Air (德安航空) is the only airline that offers flights between Lanyu Airport and Taitung Airport in Taitung City. Flight schedules are available at the airline’s Web site at www.dailyair.com.tw, though daily frequency is dependent on weather conditions. One-way tickets cost around NT$2,960.

? Ferry trips to the island are available from Fugang Harbor (富岡漁港) in Taitung year-round. The trip duration is two hour to two and half hour-long. From March to September, ferry trips are also available from Houpihu (後壁湖) in Kenting (墾丁). It takes one and half hours to two hours to travel. Round-trip tickets cost around NT$2,300.

Getting around

? The easiest way to travel around Lanyu is by renting a motorcycle (NT$400 to NT$500 per day). The only gas station is located in Yayo village, which closes at 8pm. Cars and bicycles are also available for rent. Ask your guesthouses for assistance in arranging transportation

Where to stay

? There are a lot of guesthouse and B&Bs on the island. The Chinese-language travel Web site at travel.lanyu.info contains comprehensive information about accommodation, transportation, restaurants, tourist attractions and other useful travel advice and tips.

What to bring

Geographically less accessible, Lanyu has a limited supply of goods, so prices are higher and choice is limited. It may be wise to bring some food when coming in the winter, as most eateries are closed.

? Also, always check weather forecast if you plan to go during the colder months. The weather can change dramatically. One day you will need a heavy winter coat; the next day it will be nearly 30 degrees Celsius and very summery.

The not-to-do list

? There are many taboos in the Tao culture, and tourists should demonstrate etiquette and respect. For example, visitors should take shoes off when entering a traditional pavilion, and always ask permission to take photographs of locals, their traditional ceremonies, canoes or semi-underground houses. Women are not allowed to touch canoes.

? When in doubt, check with locals. They are mostly friendly and sociable.

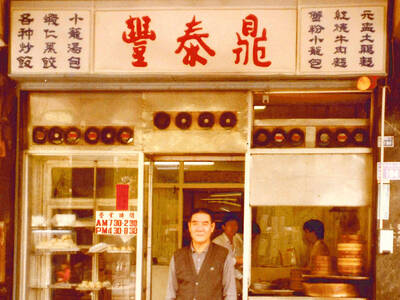

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

For the past century, Changhua has existed in Taichung’s shadow. These days, Changhua City has a population of 223,000, compared to well over two million for the urban core of Taichung. For most of the 1684-1895 period, when Taiwan belonged to the Qing Empire, the position was reversed. Changhua County covered much of what’s now Taichung and even part of modern-day Miaoli County. This prominence is why the county seat has one of Taiwan’s most impressive Confucius temples (founded in 1726) and appeals strongly to history enthusiasts. This article looks at a trio of shrines in Changhua City that few sightseers visit.