Taiwan in Time: March 14 to March 20

On May 11, 1985, student protesters marched through the National Taiwan University (NTU) campus shouting “general elections (普選)” and “I love NTU.”

Mirroring the era’s national political situation, only class representatives could vote for student president. School officials tried to stop the students, who had been calling for direct elections since 1982, but after some fierce arguing, the students went ahead with the plan.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

Taiwan was still under martial law and public gatherings were illegal. Students were handed demerits by the school and nothing would change for a few more years.

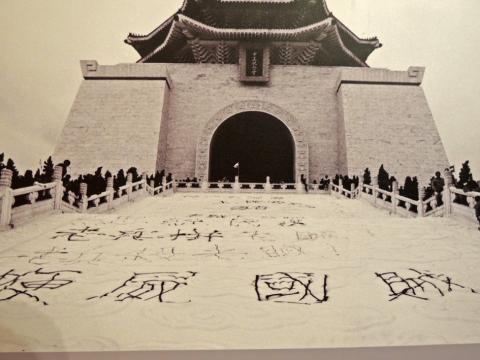

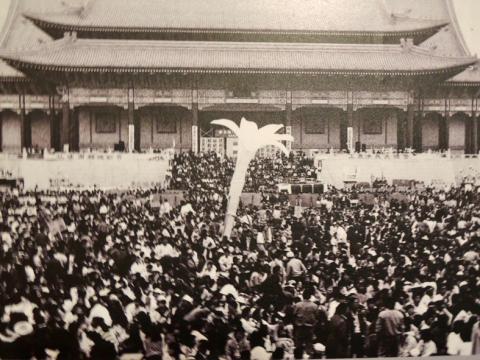

But this event marked the first open student operation after years of simmering campus unrest. It started with the clandestine circulation of flyers about free speech in 1981 and culminated in the massive Wild Lily Student Movement (野百合學運), where students occupied Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Square (today’s Liberty Square) from March 16 to March 22, 1990.

For decades, campus voices had largely been silent. Student protests over police brutality on April 6, 1949 led to mass arrests and several alleged executions.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

When martial law was declared a month later, which lasted 38 years, schools were militarized and all activities placed under strict government control as the country hurtled towards the dark years of the White Terror era.

THE TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN’

Teng Pi-yun (鄧丕雲) writes in his book, A History of Taiwan Student Movements in the 80s (80年代台灣學生運動史) that although school activities were still heavily monitored in the late 1970s, the political situation was changing with the rise of the dangwai (黨外, outside the party) movement and its publications critical of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, which were often passed around in secret on campus.

During the early 1980s, campus activism was limited to unorganized small groups who called for more freedom of expression through underground posters, graffiti and campus rallies and speeches. Off-campus, some students helped with dangwai campaigns and activities — but faced punishment if their schools found out.

“The biggest difference [before martial law was lifted] was the high level of risk that came with any type of activity,” Teng writes. “Student activists faced a great deal of uncertainty, not knowing what would happen to them.”

But it was no longer the 1950s, and most of the time students just received warnings, demerits and, at worst, expulsion.

Meanwhile, student publication staff were in frequent conflict with school officials, who had to approve all output beforehand. Many publications were suspended, shut down or restructured for bypassing the censor or writing “inappropriate” commentary. This led to the proliferation of underground publications such as National Central University’s Wildfire (野火) and NTU’s Love for Freedom (自由之愛).

Kuo Kai-ti (郭凱迪) writes in a study of Taiwanese student movements that the staff at these publications felt government suppression most directly, and often became the first to take part in student movements.

Teng writes that the first organized movement with a clear objective took place in September 1982, when several NTU clubs banded together before the student government elections and called for change to the system. With their publications censored and activities blocked, the members mostly operated by privately distributing brochures and fliers, including one that appeared on election day that urged the class representatives to boycott the election.

School punishments didn’t deter this emerging revolutionary spirit, as students and school authorities fought back and forth throughout the early 1980s, and by the protests of 1985, it had gone from covert operations to open gatherings. There was no going back.

EXPANDING INTERESTS

Taiwan’s political climate changed dramatically in the second half of the decade, most significantly with the lifting of martial law in 1987. Activists expanded their interests from school affairs to social issues and partook in environmental protection and farmers’ rights movements.

Teng writes that this fervor boiled over to politics relatively late, and started with students challenging campus norms such as inviting members of the opposition movement to speak and holding memorials and forums for the long-suppressed 228 Incident.

Pro-independence student groups would later stage silent protests after independence activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) self-immolated in 1989, and others provided support for political candidates for elections.

“These activities were like a warm-up for the events to come,” Teng writes.

Tension rose as the March 1990 presidential elections approached. Even though martial law was over, people were still not allowed to vote as the KMT-only candidates were nominated and voted in by members of the National Assembly. These “representatives” were supposed to be popularly elected — but there hadn’t been an election since 1947, earning them the moniker “Ten-thousand year congress (萬年國會).”

Reminiscent of how they stood up against the NTU election system in 1985, students this time took to the national stage, calling for political reform and true democracy as they marched into what is today Liberty Square.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,