Taiwan in Time: March 14 to March 20

On May 11, 1985, student protesters marched through the National Taiwan University (NTU) campus shouting “general elections (普選)” and “I love NTU.”

Mirroring the era’s national political situation, only class representatives could vote for student president. School officials tried to stop the students, who had been calling for direct elections since 1982, but after some fierce arguing, the students went ahead with the plan.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

Taiwan was still under martial law and public gatherings were illegal. Students were handed demerits by the school and nothing would change for a few more years.

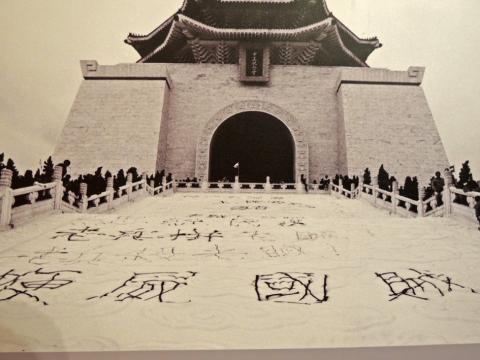

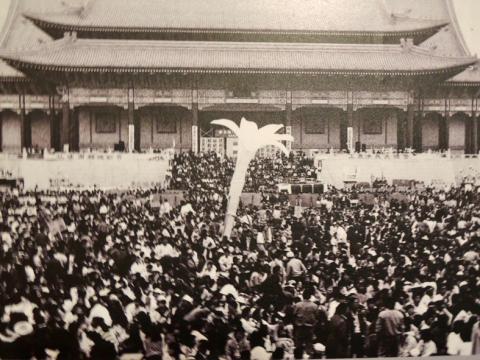

But this event marked the first open student operation after years of simmering campus unrest. It started with the clandestine circulation of flyers about free speech in 1981 and culminated in the massive Wild Lily Student Movement (野百合學運), where students occupied Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Square (today’s Liberty Square) from March 16 to March 22, 1990.

For decades, campus voices had largely been silent. Student protests over police brutality on April 6, 1949 led to mass arrests and several alleged executions.

Photo: Tang Chia-lin, Taipei Times

When martial law was declared a month later, which lasted 38 years, schools were militarized and all activities placed under strict government control as the country hurtled towards the dark years of the White Terror era.

THE TIMES THEY ARE A CHANGIN’

Teng Pi-yun (鄧丕雲) writes in his book, A History of Taiwan Student Movements in the 80s (80年代台灣學生運動史) that although school activities were still heavily monitored in the late 1970s, the political situation was changing with the rise of the dangwai (黨外, outside the party) movement and its publications critical of the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, which were often passed around in secret on campus.

During the early 1980s, campus activism was limited to unorganized small groups who called for more freedom of expression through underground posters, graffiti and campus rallies and speeches. Off-campus, some students helped with dangwai campaigns and activities — but faced punishment if their schools found out.

“The biggest difference [before martial law was lifted] was the high level of risk that came with any type of activity,” Teng writes. “Student activists faced a great deal of uncertainty, not knowing what would happen to them.”

But it was no longer the 1950s, and most of the time students just received warnings, demerits and, at worst, expulsion.

Meanwhile, student publication staff were in frequent conflict with school officials, who had to approve all output beforehand. Many publications were suspended, shut down or restructured for bypassing the censor or writing “inappropriate” commentary. This led to the proliferation of underground publications such as National Central University’s Wildfire (野火) and NTU’s Love for Freedom (自由之愛).

Kuo Kai-ti (郭凱迪) writes in a study of Taiwanese student movements that the staff at these publications felt government suppression most directly, and often became the first to take part in student movements.

Teng writes that the first organized movement with a clear objective took place in September 1982, when several NTU clubs banded together before the student government elections and called for change to the system. With their publications censored and activities blocked, the members mostly operated by privately distributing brochures and fliers, including one that appeared on election day that urged the class representatives to boycott the election.

School punishments didn’t deter this emerging revolutionary spirit, as students and school authorities fought back and forth throughout the early 1980s, and by the protests of 1985, it had gone from covert operations to open gatherings. There was no going back.

EXPANDING INTERESTS

Taiwan’s political climate changed dramatically in the second half of the decade, most significantly with the lifting of martial law in 1987. Activists expanded their interests from school affairs to social issues and partook in environmental protection and farmers’ rights movements.

Teng writes that this fervor boiled over to politics relatively late, and started with students challenging campus norms such as inviting members of the opposition movement to speak and holding memorials and forums for the long-suppressed 228 Incident.

Pro-independence student groups would later stage silent protests after independence activist Deng Nan-jung (鄭南榕) self-immolated in 1989, and others provided support for political candidates for elections.

“These activities were like a warm-up for the events to come,” Teng writes.

Tension rose as the March 1990 presidential elections approached. Even though martial law was over, people were still not allowed to vote as the KMT-only candidates were nominated and voted in by members of the National Assembly. These “representatives” were supposed to be popularly elected — but there hadn’t been an election since 1947, earning them the moniker “Ten-thousand year congress (萬年國會).”

Reminiscent of how they stood up against the NTU election system in 1985, students this time took to the national stage, calling for political reform and true democracy as they marched into what is today Liberty Square.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

There is a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) plot to put millions at the mercy of the CCP using just released AI technology. This isn’t being overly dramatic. The speed at which AI is improving is exponential as AI improves itself, and we are unprepared for this because we have never experienced anything like this before. For example, a few months ago music videos made on home computers began appearing with AI-generated people and scenes in them that were pretty impressive, but the people would sprout extra arms and fingers, food would inexplicably fly off plates into mouths and text on

On the final approach to Lanshan Workstation (嵐山工作站), logging trains crossed one last gully over a dramatic double bridge, taking the left line to enter the locomotive shed or the right line to continue straight through, heading deeper into the Central Mountains. Today, hikers have to scramble down a steep slope into this gully and pass underneath the rails, still hanging eerily in the air even after the bridge’s supports collapsed long ago. It is the final — but not the most dangerous — challenge of a tough two-day hike in. Back when logging was still underway, it was a quick,

From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law. To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum. In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions

In the run-up to World War II, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, Nazi Germany’s military intelligence service, began to fear that Hitler would launch a war Germany could not win. Deeply disappointed by the sell-out of the Munich Agreement in 1938, Canaris conducted several clandestine operations that were aimed at getting the UK to wake up, invest in defense and actively support the nations Hitler planned to invade. For example, the “Dutch war scare” of January 1939 saw fake intelligence leaked to the British that suggested that Germany was planning to invade the Netherlands in February and acquire airfields