Hot on the heels of the success of his debut novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon, American author Vern Sneider spent the summer of 1952 in Taiwan researching his next book.

Ushered in by the 228 Incident of 1947, the White Terror era was at its most brutal at that time as thousands of suspected political dissidents were imprisoned or executed by the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

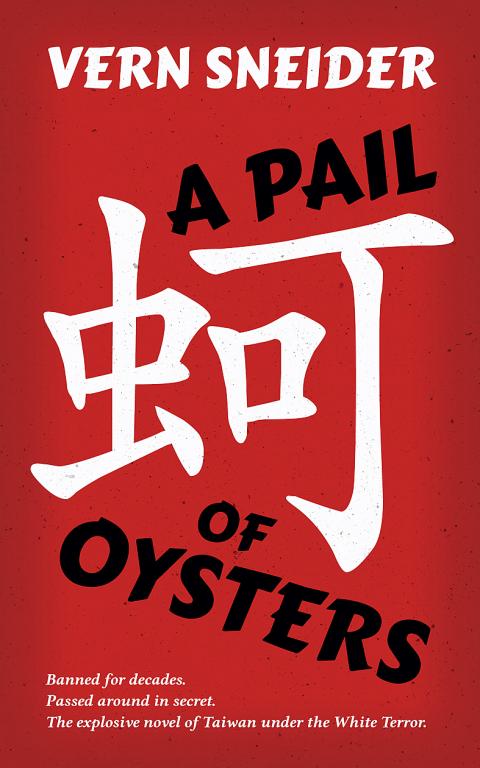

The resulting book, A Pail of Oysters, was banned in Taiwan, but to Sneider’s dismay, even the US denounced it. It was the McCarthy era, and anything portraying the KMT in a negative light was inevitably painted as pro-communist. It went out of print shortly after.

Photo courtesy of camphor press

While Mandarin and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) translations have been available since 2003, English editions are rare (rumor has it that pro-KMT students hunted down and destroyed copies from US libraries), with Abebooks.com just listing six copies, ranging from about NT$900 to NT$3,800.

“It’s one of those books that were passed around in secret during the bad old days,” Taiwan and UK-based Camphor Press cofounder Mark Swofford says.

Camphor Press is today releasing the first republishing of the book since the 1950s in digital format, with a print edition to come soon.

“It was suppressed and never got a fair hearing. We want to give it one,” Swofford says.

The book depicts life during White Terror through a variety of characters — most prominently Li Liu, a half-Hakka and half-Aborigine whose family is robbed by KMT soldiers at the beginning of the novel.

But bashing the KMT isn’t the point of the novel, Swofford says.

“It’s a very complex novel, [written] when many people thought it was just the communists versus the KMT,” he says. “It was more of a middle way sort of thing; from the standpoint of the Taiwanese people.”

RE-INTRODUCTION

Late last year, Jonathan Benda, a lecturer at Boston’s Northeastern University, found himself interviewing Sneider’s 85-year-old widow, June.

Benda was familiar with A Pail of Oysters. He read it during his 18-year stay in Taiwan and published an academic paper on it in 2007. Benda says he had once considered republishing it, but lacked the means to do so — and was surprised when Camphor Press asked him to write the introduction to their new edition.

Benda was eager to learn more about the book. In addition to speaking to June, he also dug up old articles and correspondences and obtained copies of the author’s notes through his hometown museum in Monroe, Michigan.

Stationed in Okinawa and Korea, Sneider had never been to Taiwan before the summer of 1952, but the US Army had him study the country at Princeton University in preparation for possible military occupation during the war.

Benda was impressed with the amount of research Sneider’s notes contained — including interviews with people ranging from then-governor K.C. Wu (吳國楨) to pedicab operators and extensive notes on items such as how children are named and blind masseuses. He even had his palm read, which is featured in the novel.

“It’s easy to point out mistakes or problems with his depictions … but I come away thinking that he got a lot of it right,” Benda says.

Through examining letters, Benda found that Sneider had hoped to counter the pervading pro-KMT perception of Taiwan as “Free China” and show how its people were actually suffering under martial law.

“My viewpoint will be strictly that of the Formosan people, trying to exist under that government,” he wrote to George H. Kerr, author of Formosa Betrayed. “And … maybe, in my small way, I can do something for the people of Formosa.”

But although Sneider was critical of the government, he generally gives a balanced picture, including democracy proponents in the KMT and sympathetic soldiers, Benda says.

In addition, the American perspective is shown through the eyes of Ralph Barton, a journalist investigating life in Taiwan under martial law — which corresponds to Sneider’s role, except that the author believed that fiction is a more powerful vehicle through its “emotional pull,” as detailed in his letter to Kerr.

Sneider died in 1981 — too early for any chance to redeem his book, but at least June is able to see it happen.

“She was glad to have this out during her lifetime,” Swofford says.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Politically charged thriller One Battle After Another won six prizes, including best picture, at the British Academy Film Awards on Sunday, building momentum ahead of Hollywood’s Academy Awards next month. Blues-steeped vampire epic Sinners and gothic horror story Frankenstein won three awards each, while Shakespearean family tragedy Hamnet won two including best British film. One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s explosive film about a group of revolutionaries in chaotic conflict with the state, won awards for directing, adapted screenplay, cinematography and editing, as well as for Sean Penn’s supporting performance as an obsessed military officer. “This is very overwhelming and wonderful,” Anderson

Another moment of the US making permanent concessions for transient gains, which appears to be longstanding US policy with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), occurred last week when President Donald Trump announced that weapons sales to Taiwan would be delayed in order to arrange a meeting with the PRC dictator Xi Jinping (習近平). There were “concerns among some in the Trump administration that greenlighting the weapons deal would derail Trump’s coming visit to Beijing, according to US officials,” the Wall Street Journal reported. It attributed the suspension of the weapons sale to pressure from Xi. While some might shrug