Hot on the heels of the success of his debut novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon, American author Vern Sneider spent the summer of 1952 in Taiwan researching his next book.

Ushered in by the 228 Incident of 1947, the White Terror era was at its most brutal at that time as thousands of suspected political dissidents were imprisoned or executed by the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

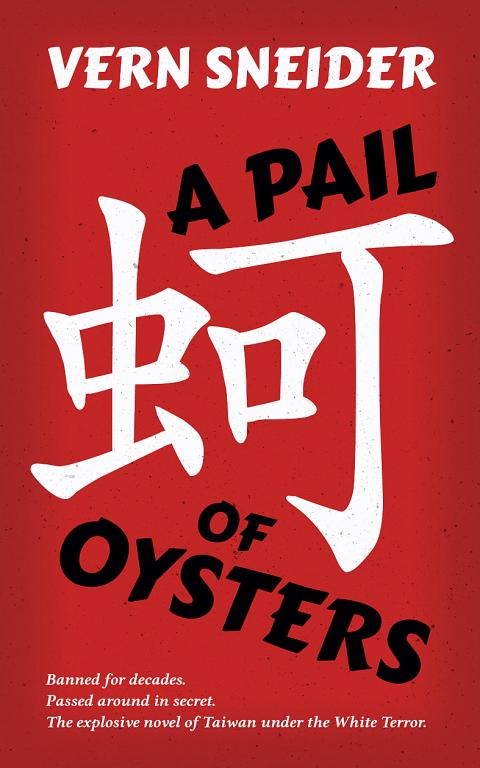

The resulting book, A Pail of Oysters, was banned in Taiwan, but to Sneider’s dismay, even the US denounced it. It was the McCarthy era, and anything portraying the KMT in a negative light was inevitably painted as pro-communist. It went out of print shortly after.

Photo courtesy of camphor press

While Mandarin and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) translations have been available since 2003, English editions are rare (rumor has it that pro-KMT students hunted down and destroyed copies from US libraries), with Abebooks.com just listing six copies, ranging from about NT$900 to NT$3,800.

“It’s one of those books that were passed around in secret during the bad old days,” Taiwan and UK-based Camphor Press cofounder Mark Swofford says.

Camphor Press is today releasing the first republishing of the book since the 1950s in digital format, with a print edition to come soon.

“It was suppressed and never got a fair hearing. We want to give it one,” Swofford says.

The book depicts life during White Terror through a variety of characters — most prominently Li Liu, a half-Hakka and half-Aborigine whose family is robbed by KMT soldiers at the beginning of the novel.

But bashing the KMT isn’t the point of the novel, Swofford says.

“It’s a very complex novel, [written] when many people thought it was just the communists versus the KMT,” he says. “It was more of a middle way sort of thing; from the standpoint of the Taiwanese people.”

RE-INTRODUCTION

Late last year, Jonathan Benda, a lecturer at Boston’s Northeastern University, found himself interviewing Sneider’s 85-year-old widow, June.

Benda was familiar with A Pail of Oysters. He read it during his 18-year stay in Taiwan and published an academic paper on it in 2007. Benda says he had once considered republishing it, but lacked the means to do so — and was surprised when Camphor Press asked him to write the introduction to their new edition.

Benda was eager to learn more about the book. In addition to speaking to June, he also dug up old articles and correspondences and obtained copies of the author’s notes through his hometown museum in Monroe, Michigan.

Stationed in Okinawa and Korea, Sneider had never been to Taiwan before the summer of 1952, but the US Army had him study the country at Princeton University in preparation for possible military occupation during the war.

Benda was impressed with the amount of research Sneider’s notes contained — including interviews with people ranging from then-governor K.C. Wu (吳國楨) to pedicab operators and extensive notes on items such as how children are named and blind masseuses. He even had his palm read, which is featured in the novel.

“It’s easy to point out mistakes or problems with his depictions … but I come away thinking that he got a lot of it right,” Benda says.

Through examining letters, Benda found that Sneider had hoped to counter the pervading pro-KMT perception of Taiwan as “Free China” and show how its people were actually suffering under martial law.

“My viewpoint will be strictly that of the Formosan people, trying to exist under that government,” he wrote to George H. Kerr, author of Formosa Betrayed. “And … maybe, in my small way, I can do something for the people of Formosa.”

But although Sneider was critical of the government, he generally gives a balanced picture, including democracy proponents in the KMT and sympathetic soldiers, Benda says.

In addition, the American perspective is shown through the eyes of Ralph Barton, a journalist investigating life in Taiwan under martial law — which corresponds to Sneider’s role, except that the author believed that fiction is a more powerful vehicle through its “emotional pull,” as detailed in his letter to Kerr.

Sneider died in 1981 — too early for any chance to redeem his book, but at least June is able to see it happen.

“She was glad to have this out during her lifetime,” Swofford says.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the