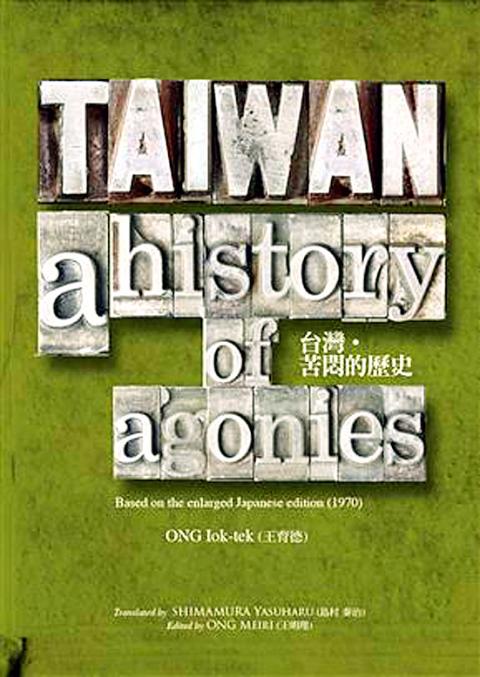

Ong Iok-tek’s (王育德) Taiwan: A History of Agonies has finally become available in English. Originally written in Japanese and translated into Chinese, its long-awaited English translation was completed last year. For that reason, Ong (1924—1985) may not be a household name among many in the West who study Taiwanese history, but that does not diminish the valuable insights and contributions of this work.

To place Ong in context, he was born in Taiwan in 1924 during the Japanese colonial era, and was a contemporary of Su Beng (史明, b.1918), a historian and Taiwan independence advocate, former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝, b. 1923) and democracy pioneer Peng Ming-min (彭明敏, b. 1923), all Taiwanese who studied in Japan.

Parallels can be found between Ong’s book and Su Beng’s 400 Years of Taiwan History. Both books were originally written in Japanese. Su’s 400 Years was written in 1962; Ong’s History of Agonies in 1964. Both were later translated into Chinese and would be instrumental in informing Taiwanese of their past. Ong’s book was translated into Chinese in 1977; Su’s was translated in 1980. Su’s book would further be translated into English in 1986, whereas Ong’s English version was published last year.

Su and Ong both fled to Japan where they moved in different circles. Ong returned to his studies in 1949 and went on to get a doctorate in literature at the University of Tokyo; he would work with developing Taiwan support groups in intellectual and international spheres. Su escaped Taiwan in 1952 and would continue as a revolutionary, training insurgents to return to Taiwan.

Ong’s book is for those researching Taiwanese consciousness post-WWII. What makes it unusual is not just the historical content, much of which can now be found in other contemporary works, but the realization that awareness of Taiwan’s history and identity had reached a state of maturity in Japan by 1964.

Taiwan of course was under martial law and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) controlled most discourse coming out of the nation to the English-speaking world. In 1964, Peng was arrested on charges of treason for his pamphlet Declaration of Formosan Self-Salvation. In the following year, Lee left Taiwan to study for a doctorate at Cornell University.

While in Japan, Ong kept close tabs on Taiwan-related issues, including Peng’s house arrest and later escape. In Ong’s update of 1970, he devotes several pages to Peng’s ideas and flight to Sweden. Ong’s daughter, who helped in making the English version available, stresses that her father’s lifelong aim and pursuit was, “Taiwan is not China. The Taiwanese are not the Chinese. Taiwan should be ruled by Taiwanese themselves.”

Ong’s attention to detail and his ability to draw from Japanese periodicals and other sources are added benefits. Some may be familiar with the Qing Dynasty adage: “an uprising every three years and a revolution every five years.” Ong provides a list for each uprising and revolution, including the year, names of important people and the consequences.

Ong also provides the name, position and background of over a dozen Taiwanese who were targeted and murdered during the 228 Incident and its aftermath, including his brother who was a prosecutor in the Hsinchu District Court. Ong also writes how Taiwanese later were aware that Communist China and the KMT, though at odds, were united in their efforts to suppress any suggestions of Taiwan independence

As Ong spent the final 36 years of his life in Japan, one comes to realize the extent to which Taiwanese consciousness and the support of the independence movement was housed there throughout the 1950s and 1960s. It would later shift to the US in the 1970s and 1980s as more Taiwanese did their graduate studies there. Ong was involved with these different groups and was instrumental in setting up the “Taiwan Youth Society,” which was the forerunner of World United Formosans for Independence.

The book’s preface and final chapter were added by Ong’s daughter to take it well beyond Ong’s 1970 update. She also adds a timeline which ends with the KMT’s overwhelming loss in the November 2014 nine-in-one elections.

The translation reads extremely well. Since most of the book was written in 1964 and updated in 1970, the work uses the Wade-Giles system of Romanization. One can also expect a few discrepancies in historical dates and perceptions that would be cleared up in later decades as more information became available.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on