Taiwan in Time: Feb. 1 to Feb. 7

Several decades after the death of painter Chen Cheng-po (陳澄波), his wife Chang Chieh (張捷) showed her daughter-in-law a wooden box she had kept hidden for many years.

In it were Chen’s undergarments, wrapped in paper and preserved with mothballs. There were two bullet holes on the undershirt. The daughter-in-law recalls in the book 228 at Chiayi Station (嘉義驛前二二八) that Chang told her to take good care of the clothes, along with a photo of Chen’s corpse with the bullet holes clearly visible.

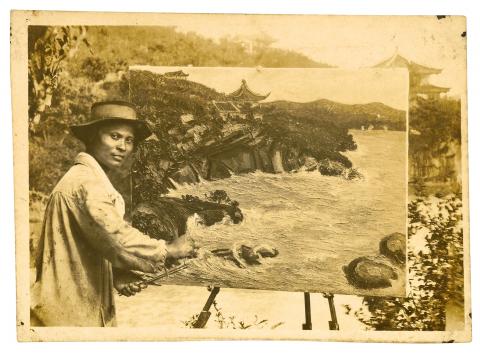

Photo: Tsai Shu-yuan, Taipei Times

“It’s proof,” Chang says. Proof that Chen was killed by government troops in 1947 during an anti-government uprising following the 228 Incident.

Chang reportedly risked her life to collect Chen’s corpse and hired a photographer to take a photo of the body, an image that is now on display at the Chiayi Municipal Museum (嘉義市立博物館).

Chen is one of those figures whose accomplishments were largely erased by politics, and his name, or at least his fate, largely disappeared from public conscious until after the lifting of martial law in 1987.

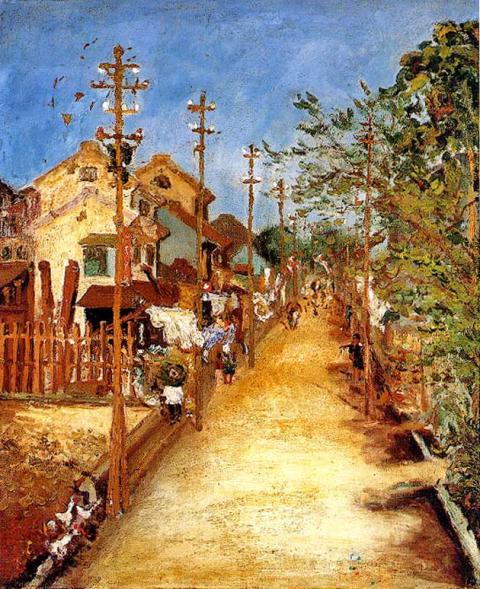

Courtesy of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts

Even the National Central Library, which has in its collection all kinds of old books that would have been considered controversial in the past, has only one item — a collection of his paintings — about Chen dating before 1987.

In the 1997 government-published children’s book, Taiwanese Artist: Chen Cheng-po (台灣美術家: 陳澄波), release two years after former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) publicly apologized to 228 victims, author Chen Chang-hua (陳長華) was able to openly mention how the artist died, though she concludes it in one sentence: “In 1947, the 228 Incident happened in Taiwan, and Chen Cheng-po, who was a city councilman, became one of the incident’s unfortunate victims.”

However, in the epilogue, Chen writes, “Chen’s artistic accomplishments were unable to be made public for a long time because of the political shadow of 228. In fact, in this open era, we should revisit Chen’s journey as an artist … to pay him further respect.”

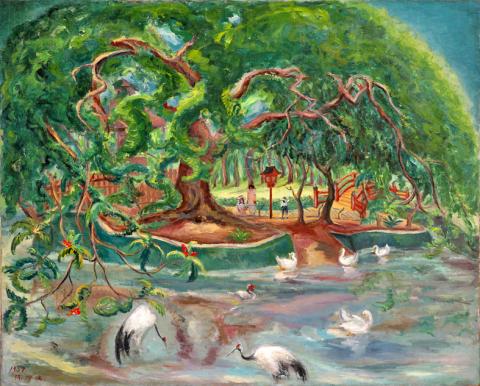

Courtesy of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts

Chen Chang-hua may be right; ever since the public became able to openly discuss Chen Cheng-po, his fate has dominated the discourse. Aside from being a 228 victim and talented artist, what do we really know about Chen?

Born on Feb. 2, 1895 in today’s Chiayi, Chen’s family wasn’t wealthy enough for him to realize his artistic aspirations, and after attending university in Taipei he returned home and taught in public schools in the area for about seven years.

By the time he was accepted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts), Chen was nearly 30 years old. In just two years, his oil painting of a street scene in Chiayi was accepted to the annual prestigious Japan Imperial Art Exhibition, and another street scene also made the show the following year. This made Chen the first Taiwanese to have a Western-style painting featured in the exhibition.

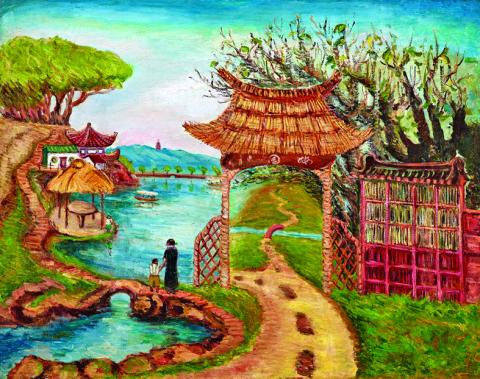

Courtesy of Liang Gallery

Chen graduated in 1929 with a degree in Western art and headed to Shanghai, where he spent four years as an art teacher. While in China, he learned traditional Chinese painting techniques, which he integrated into his techniques.

Japan invaded Shanghai in 1932, and as Japanese citizens, Taiwanese living in China also became the target of anti-Japanese sentiment. Chen returned to Chiayi in 1933 and became a full-time artist. Life wasn’t easy, as he reportedly couldn’t afford his daughter’s dowry and provided two paintings instead.

He’s reported to have said, “As someone whose mission it is to create art, if I can’t live for art and die for art, how can I call myself an artist?”

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Japanese surrendered in 1945. Since Chen learned Mandarin in Shanghai, he took up the position as vice-head of Chiayi’s Preparatory Committee to Welcome the National Government (歡迎國民政府籌備委員會).

This foray into politics would eventually seal his fate. The next year, he joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and served in the first Chiayi city council.

Historian Wang Chao-wen (王昭文) writes that when the 228 incident broke out, some of the fiercest fighting between civilians and government troops took place in Chiayi. On March 11, 1947, after a nine-day standoff between the military in the airport and armed civilians, Chen and several other representatives entered the airport in an attempt to negotiate with the government.

The military instead arrested four of the representatives, including Chen, and publicly shot them in front of Chiayi’s train station without a trial on March 25. Chen’s lifeless body lay on the streets of Chiayi, surrounded by scenes that he loved to paint so much, for three days until his wife finally ventured out and collected the corpse.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual