It was the day after the Ma-Xi meeting — the historic meeting in Singapore between Taiwanese President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) and the first time that the top leaders from both sides of the Taiwan Strait have met in person — that I spoke with Hong Kong activist Jason Ng. The lawyer-turned-best-selling-author was signing books at the Arts House in Singapore where he was a featured speaker at the Singapore Writers Festival.

“In Hong Kong, the media calls it the Xi-Ma meeting,” Ng tells me.

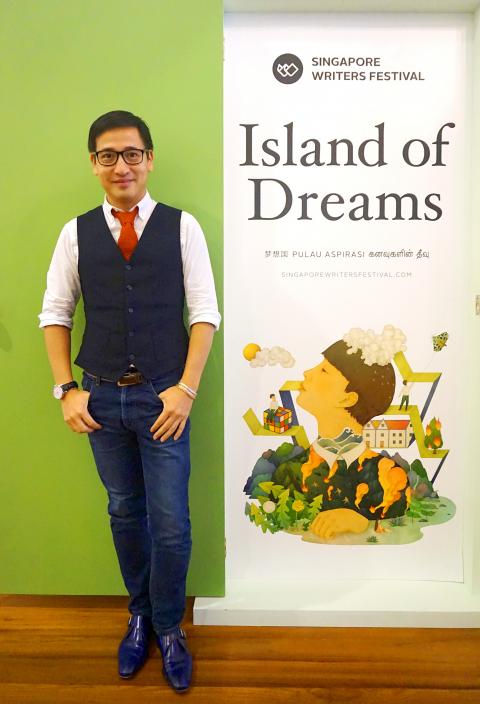

Donning thick-rimmed glasses and a form-fitting navy blue vest over a neatly-pressed shirt and red tie, Ng’s soft-spoken, scholarly demeanor belies the fact that he’s one of Hong Kong’s most outspoken activists. In addition to being chosen as Hong Kong’s “Man of the Year” by Elle Men magazine in 2011 and participating in the “Umbrella movement” last year, Ng is also a columnist for the South China Morning Post and the author of the popular blog, As I See It, where he muses about Hong Kong’s most pressing social and political issues.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Ng says that the label, “Xi-Ma meeting,” is an indication of the amount of influence that China has come to exert over the media in Hong Kong. He adds that the perceived lack of a reliable press — especially the Chinese-language press — has led many Hong Kong residents to turn to blogs and social media for other perspectives on politics and current affairs.

BATTLE OF THE WITS, SORT OF

Earlier that day, Ng had spoken about citizen journalism at a panel discussion at the Singapore Writers Festival entitled “Tweet for Change,” which touched upon different ways that authors and journalists can use social media effectively. While he largely applauds social media for having the power to reach a mass audience in a shorter amount of time — he admits that his own blog has a wider readership than his articles because blogging is faster and more up-to-date — there’s still much to be wary of.

Photo courtesy of Jason Ng

Like the other panelists — also best-selling authors all of whom maintain a strong online presence — Ng believes that 140-character tweets and powerful images on Instagram have only fed into people’s short attention spans more.

“The problem is that whoever has a wittier phrase wins because someone who actually has a point to make may not be as creative,” he says.

Although it’s arguable that social media helped to rally support for social movements such as the “Umbrella movement,” Ng is skeptical of how much tangible progress is made when people are simply sitting at home and typing a few words or changing their profile pictures on Facebook.

Photo courtesy of Jason Ng

Then, there’s a new crop of commentators who keep the snide remarks rolling.

“The political environment in Hong Kong is so toxic these days, that after I post something, there will be a response after 10 seconds — it’s like, did you even read the article?” Ng says, to which the audience snickers.

THE TAIWAN CONNECTION

Speaking with Ng in person, he expresses a deep concern about the future of Hong Kong’s democracy. With the one year anniversary of the conclusion of the “Umbrella movement” coming up, Beijing has only continued to exert its own political agenda on the former British colony.

And with Taiwan’s presidential election next month, Taiwanese have a lot on their minds too. When I tell Ng that people in Taiwan are worried about ending up like Hong Kong — with the clamping down on freedom of speech and press — he agrees that it’s a legitimate concern.

There’s a saying, he adds: “Today’s Hong Kong is tomorrow’s Taiwan.”

Moreover, Ng believes that the Sunflower movement played an inspirational role to protesters in Hong Kong.

“It helped in terms of planting a seed,” Ng says. “Even if there wasn’t overt coordination, there was still a spiritual connection at least.”

Ng was actually on vacation in Kaohsiung when the Sunflower movement broke out. He participated in a sit-in there and was asked to give a speech but declined because he felt that his Mandarin wasn’t good enough. Nevertheless, he says it was “refreshing” to see such mass mobilization happen in Taiwan, rather than in a city like New York, where he wouldn’t have given it a second thought.

“I remember telling myself that this is what it must have felt like to be in Tiananmen Square in 1989,” Ng tells me.

When I ask him why he thinks the foreign media didn’t give the Sunflower movement as extensive coverage as it did with the Umbrella revolution, his reply is simple: “there was nothing sexy.”

More often than not, the press is sensation-driven. While the Sunflower movement was largely non-violent, consisting of mostly peaceful protesters occupying the legislature to show their defiance of the cross-strait service trade agreement with China, the protests in Hong Kong — which took place on the streets and involved the police using tear gas on protesters — was far more visible.

“Some guy in Tennessee wouldn’t be interested in some people sitting inside a building in Taiwan to protest a trade pact,” Ng says.

THE COFFEE SHOP DREAM

Although Ng might have his qualms about Hong Kong’s future, he is hopeful for Taiwan. Not only did the Sunflower movement make possible the nine-in-one elections, he says, which led to the Chinese National Party (KMT) losing the Taipei mayorship, but Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) presidential candidate Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) also seems more interested in developing the economy rather than fixating on cross-strait relations.

Politics aside, people from Hong Kong have increasingly come to see Taiwan as an ideal place to live and work. Citing figures from a TVB Evening News report, Ng says the percentage of people from Hong Kong applying for permits to live in Taiwan increased by 64 percent from 2013 to last year.

Ng says this is because they are attracted to the laidback lifestyle and entrepreneurial work ethic that Taiwan has to offer. It wasn’t the case a decade ago when people from Hong Kong thought Taipei — with its grimy sidewalks and lack of skyscrapers — had much catching up to do with other Asian cities.

“There’s the allure of a slower pace of life,” Ng says. “Some of the most popular books in bookstores around Hong Kong are about how to move to Taiwan, and people are dreaming of opening coffee shops in Taipei.”

Ng has to rush off to another panel discussion and I’m wondering how he manages to look so immaculate despite the torrid Singapore heat. Nevertheless, his words left me thinking that while we may not be as zesty as activists in Hong Kong, at least we’re brewing good coffee.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move