The ground is covered with autumn leaves that smell like roasted chestnuts. They crackle as we walk. Each orange and yellow leaf appears to have been carefully arranged — so much so that it feels like we’re disturbing the peace with our footsteps.

I look to my left and make out a pair of legs partially hidden under a pile of leaves. My peripheral vision reveals what appears to be other body parts — a bruised hand, maybe a torso. Then, darkness.

A hacking sound starts as flashes of crimson and violet light appear, the truncated beats syncing with the intermittent flickers. Then, darkness again.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Now I see a wooden table scattered with dozens of little sketches — diagrams, taxonomies of various insect species and human organs. A coffee cup had tilted over, causing it to spill onto some of the sketches. But like the dead body in the woods, there’s beauty to the mess, a system to the disorder.

A naked man appears. His back is walking away. The hacking noise grows louder and he’s gone. The corpse is back, with beetles crawling all over it, and one nestled snugly in the palm of the bruised hand. The lights return. This time, it’s a spotlight circling, as if searching for something.

The murderer. Where did he go?

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

CRITIQUING FACTS, OBFUSCATING TRUTH

Had I really witnessed a murder? Or did I simply pick up on some cues and my imagination led me to believe that I had?

“Fact is not real. It’s what people perceive something to be. Our brains assemble bits and pieces of images, noises, smells and we come up with our own truths,” says Wang Jun-jieh (王俊傑), the artistic director of the haunting kinetic installation piece I had just saw.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Held at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Night of Sodom (索多瑪之夜) is a collaborative exhibition involving artists, videographers and technicians. It draws inspiration from the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, which tells the tale of four wealthy men who engage in a series of orgies in a harem with 46 teenagers, both male and female. Written in 1785 when he was imprisoned in the Bastille, Sade thought that the manuscript, which he hid in the prison’s walls, was lost forever during the storming of the Bastille in 1789. It survived, but was not discovered until the early 20th century and, due its controversial subject matter, only became widely circulated decades later.

Wang, who is also chief director of the Center for Art and Technology at Taipei National University of the Arts, says that on the surface, the novel may seem like “a celebration of evil, or, of orgies.”

In fact, Wang’s interpretation of the text is that it’s not so much pornographic or scandalous, but about how Sade reconstructs the notion of fact by overlapping various viewpoints and thereby obfuscating the truth. Likewise, the exhibition — which is restricted to visitors age 18 and above — disrupts the natural viewing process one would expect at a museum by presenting viewers with a multisensory experience and a plot that does not follow a linear narrative, the result of which is both frustrating and satisfying.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

MORE QUESTIONS THAN ANSWERS

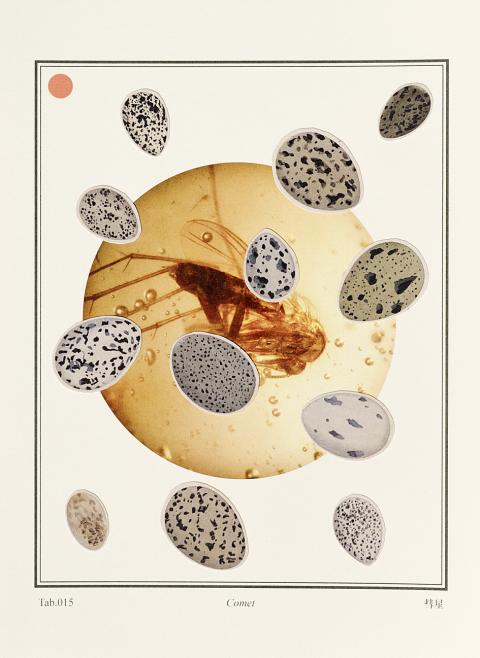

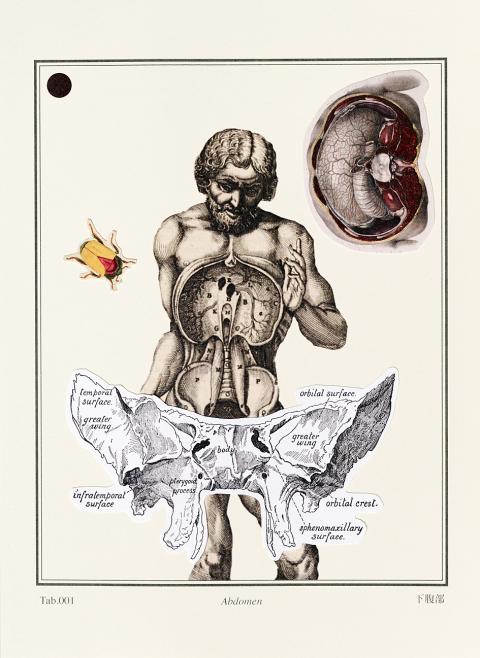

The first part of the exhibition actually takes place in a small room filled with scientific-looking collages consisting of illustrations and their corresponding descriptions. The images from the collages were recycled from old encyclopedias Wang and his team collected from libraries around Taiwan. However, they are cut and pasted in such a way that the meaning has been altered — for instance, egg shells are categorized under comets. In the center of the room sits a horizontal glass case (or casket?) with feathers swirling about.

“You’re supposed to incorporate the stimulus from the performance and use that to reinterpret the initial space,” Wang says.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Returning to the room, I half-expected to see a dead body in the glass case. But even with this new “knowledge,” nothing seems right. Insects which are normally thought to be disgusting are cast in a majestic light, the eerie woods feel remarkably serene and death is rendered beautiful — desirable almost. That is, if anyone had even died.

At the end of the screening the audience is left with more questions than answers. The effect is intentional, though, since for Wang, contemporary art is meant to stimulate thought and discussion.

“I’m happier if people leave with more questions,” he says. “It means that the exhibition was successful.”

Wang also expects viewers to have different impressions or interpretations (I seemed to be one of the few people who found the exhibition calming instead of terrifying). This not only shows the subjective nature of truth, but it also draws the audience into the performance in a way that is more subtle than shuffling about in dried leaves. Thinking is an active process and by projecting our own opinions onto the exhibition space, the meaning of the artwork is constantly in flux.

DOWN WITH THE SYSTEM

Another aspect of Sade’s work that resonates with Wang is how Sade used the system to criticize the system. The misogynistic violence and slaughter that takes place in The 120 Days of Sodom can be interpreted as a hyperbolic snide to King Louis XVI’s gluttonous reign. Similarly, Night of Sodom turns a critical eye on itself by using new media to reveal the destructive tendencies of technology.

“Civilization was built upon technology but will be destroyed if we continue to use it in a manner that’s totally out of control,” Wang says.

While Wang wishes to criticize how big data and information technology has shaped the way we think, it’s the little details in the exhibition that matter. The diagrams from the screening are sketched out with murderous precision, as if the angle and contour of every organ has been measured and drawn to scale.

The collages that we see in the room before the screening is also satirical in the sense that it constructs a new classification or naming system, when the entire purpose of the exhibition is to illustrate how systems are innately absurd. But at the same time, there’s also an aesthetical beauty to the meticulous categorization.

Wang says that the scientific motifs were inspired by French artist Marcel Duchamp, who, in 1913, was feeling disillusioned by the art world, and took a break from painting to work as a librarian. During this time, Duchamp studied math and physics, and started to mix his passions by creating artwork using scientific experiments.

Night of Sodom, in turn, can be seen as an experiment, and the viewers, its unknowing test subjects. What it succeeds in the most is demonstrating how technology plays with our minds to the point where we’re not controlling it, but it’s controlling us.

That being said, perhaps the exhibition, with all its minute details, is one big allegory. It doesn’t matter if a murder took place or not. What matters more is how technology has wired our brains to process and package information in a systematic way, and also, that we might be happier and freer if this wasn’t the case.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she