The first gun I shot was a .22 long rifle outside a friend’s cabin in Copemish, Michigan. A beginner’s gun. Terrified by the thought that I was holding in my hand a machine that was designed to kill people, I repeated my friend’s instructions over and over in my head — lean my right shoulder blade into the butt of the rifle, position my left foot in front of my right foot, squint my left eye, focus my right eye on the target, rest my right index finger on the trigger.

Bang! Once the bullet left the barrel, my fear was suddenly replaced by elation. It didn’t matter that I was way off target — I had just shot a rifle.

Ever since that day a few years ago, I’ve been hooked. While I’m far from being a sharp shooter, I’m addicted to the feeling I get when my finger pulls the trigger, unleashing a torpedoing bullet along with a deafening noise that makes my heart skip a beat.

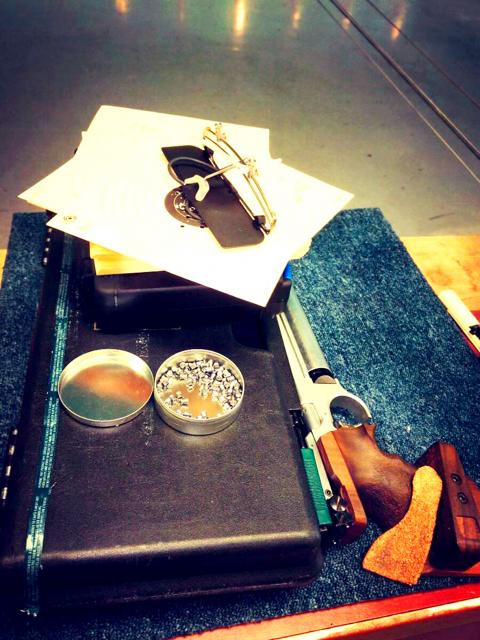

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

While recreational shooting — whether it’s practicing for competitions, game hunting or simply firing at targets for the sake of it — is commonplace in the US, such is not the case in Taiwan because of stricter gun control laws. So you can imagine my excitement when I found out that the Taipei Zhongzheng Sports Center (台北市中正運動中心) near Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall had a 10m shooting range on the sixth floor.

FUN WITH (AIR) GUNS

The first letdown came when I was told beforehand that the shooting range used air guns, not real guns. Convincing myself that it would still be cool, I went anyways. The second letdown was when I stepped inside the shooting range. Nearly everyone was below the age of 18. The air rifles resembled water guns more than they did real guns. The pellets looked more like pins than bullets. A toddler wedged herself between my legs and the wooden ledge where the air guns were poised and scampered across a row of teenagers aiming their air pistols at paper targets.

Photo courtesy of Luo Hsiao-fang

Firing an air rifle felt nothing like firing a real rifle. There’s no loud noise, hence no need for earmuffs, and no recoil, which means no sense of bewilderment that you just fired a gun. A middle-aged man who appeared to be a coach approached me and complimented my stance. Trying to hide my disappointment, I told him I’ve shot real guns before. I learned that the students are part of the Taipei Shooting Sports Association (台北市體育總會射擊協會) and the man, Hsieh Chien-hua (謝建華), is the head coach.

The Taipei City government opened the indoor shooting range as a target practice venue for air gun shooting competitions. Due to Taiwan’s strict gun control laws, there are very few places where civilians can fire real guns. The outdoor clay shooting ranges in Linkou (林口) and Kenting (墾丁) are two popular ones.

“Taiwan’s gun control laws are put in place for good measure,” Hsieh says, adding that even air guns could seriously injure people if they are not handled properly.

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

He adds that “it’s important to cultivate a culture where children learn about safety.”

I glance around and notice that the students are scribbling in their workbooks in between shots. Their textbooks look heavier than the air guns.

“Air gun shooting is all about concentration,” Hsieh tells me. “It’s a skill which will benefit the children in other areas of life too.”

Photo courtesy of Tobie Openshaw

SHARP-SHOOTING KIDS

His students, who all hail from different high schools and have been shooting for at least three years, are extremely dedicated. One of them, Chen Shi-heng (陳士亨) says he’s at the shooting range six times a week, from Tuesday to Sunday (the sports center is closed on Mondays).

Although they joke around and peer at each other’s workbooks during their breaks, when it’s time to shoot, the students are dead serious. Donning blinders to block out peripheral distractions, they hold their air pistols steady with their right hands, while their left hands rest snugly in their pockets. Looking dead straight at their targets, they release their triggers almost simultaneously.

Photo courtesy of Luo Hsiao-fang

Unable to contain myself any longer, I ask the students if they think firing a real gun will be cooler than an air gun. They stare at me blankly, unable to fathom my excitement when I recount my experience shooting an M-16 in Vietnam.

“I don’t see a difference with using a real gun and an air gun,” Chen says. “The techniques are similar and I think the feeling that I would get from firing a real gun wouldn’t be too different.”

Another student, Su Pin-chia (蘇品嘉) chimes in. “It’ll be cool if I could use a real gun for target practice one day, but it’s not a big deal if I don’t have one right now.”

Haven’t they ever watched Rambo, Lethal Weapon or just about any cowboy or action movie, I ask.

“We didn’t really grow up watching those kinds of movies,” Chen says, half-laughing at me, as if to say that a pop culture that glamorizes the use of guns was silly.

Apparently, it’s about putting a pellet through a sheet of paper, not blowing up bad guys. Such a sport requires precision and concentration, leaving no room for rash behavior.

Lee Yu-cheng (李祐呈), an older student who’s competed in air gun competitions overseas, agrees with the other two. Yet despite his love for the sport, Li adds that “for now, air gun shooting is somewhat of a hobby.”

He says that the plan is to have a “real job” when he grows up, but to still come to the shooting range for regular target practice.

Kudos to them, but I’m planning for my next rendezvous to be with a real rifle in Linkou or Kenting.

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

Last week Elbridge Colby, US President Donald Trump’s nominee for under secretary of defense for policy, a key advisory position, said in his Senate confirmation hearing that Taiwan defense spending should be 10 percent of GDP “at least something in that ballpark, really focused on their defense.” He added: “So we need to properly incentivize them.” Much commentary focused on the 10 percent figure, and rightly so. Colby is not wrong in one respect — Taiwan does need to spend more. But the steady escalation in the proportion of GDP from 3 percent to 5 percent to 10 percent that advocates

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,

A series of dramatic news items dropped last month that shed light on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attitudes towards three candidates for last year’s presidential election: Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲), Terry Gou (郭台銘), founder of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), and New Taipei City Mayor Hou You-yi (侯友宜) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It also revealed deep blue support for Ko and Gou from inside the KMT, how they interacted with the CCP and alleged election interference involving NT$100 million (US$3.05 million) or more raised by the