The moment I started reading A Far Circle, an account of two and a half years living with driftwood-carvers and musicians on Taiwan’s south-east coast, I recognized what it was. Despite being published by a university press, this is another item in the long history of Bohemianism, a way of life that involves giving up on the rat-race, living among “marginal” peoples, putting art before profit, and embracing what used to be called the “counter-cultural” principles of free love, strumming your guitar as the sun sets over the ocean, sharing rather than buying and selling, and generally living a peaceful and uncompetitive life in harmony with whatever’s left of nature.

Scott Ezell arrived in Taiwan from his native US in 1992, worked in Taipei for 10 years as a translator and musician, then moved to the coast north of Taitung in 2002. His subsequent problems with the authorities over his visa gained him some unwelcome publicity — an apparently over-zealous police-officer became convinced his musical activities violated the conditions of his ARC, and he eventually left Taiwan of his own free will. An article on his case, Singing the Deportation Blues, appeared in the Taipei Times on June 20, 2004. Earlier this year he returned to Taiwan to take up an artist’s residency close to where he used to live in the coastal village of Dulan (都蘭), following a brief return visit in 2013.

Almost by definition, people who opt to take up the Bohemian life-style come from a very different background. Ezell’s appears to have been essentially academic, and the resulting combination of earthy experience and a scholarly awareness makes for a strong book, as well as a highly readable one. But the tale it tells is an old one, and early on I was thinking of Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, describing impoverished Beats with a Buddhist vision in 1950s California, only to find the book mentioned twice in Ezell’s text.

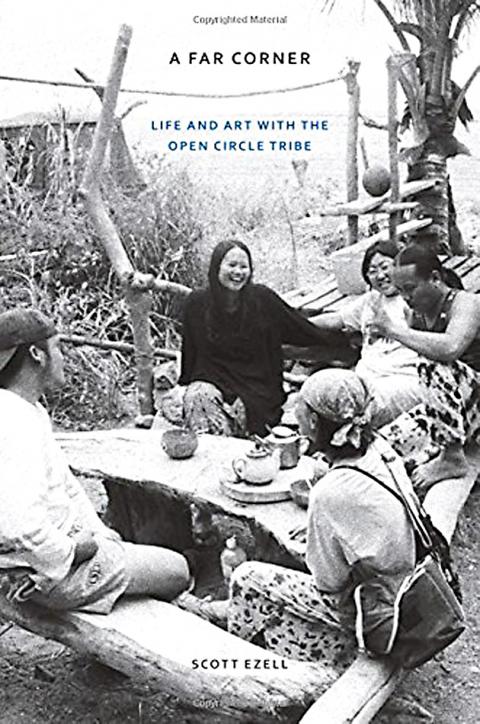

The world Ezell embraced in 2002 was one of Amis and other Taiwanese Aboriginals carving sculptures using chain-saws from often huge pieces of driftwood, drinking rice wine, chewing betel-nut and generally living a life of communal ease in Taiwan’s relatively pristine south-east. The group of friends informally called themselves the Open Circle Tribe, and have since become known as significant and saleable artists; they’ve even had doctorates written about them. But 13 years ago they were unknown to the outside world.

Life-style and artistic creativity are different things, though, even if it’s part of the Bohemian credo that to some extent everyone’s an artist. Ezell did build the only beach sculpture to survive a particularly ferocious typhoon, but his preferred art was composition. His “landscape painting in music” evoking the ocean, also called wordless songs or “organic folk,” was exemplified by his 2003 album Ocean Hieroglyphics, recorded in what he calls the only analog studio in Taiwan, situated in a remote house for which he paid NT$2,000 a month rent.

But Ezell is also a poet, and it’s this aspect of his personality that’s most strikingly in evidence in this fine book. On one page alone he describes July as “the gut and groin of summer,” clouds as “coronations of white,” plus “the crash and roar of the sun,” and the sky “a bored god, butane blue.” Elsewhere someone is as “inexpressive as a sea urchin,” a snake is “a squiggle of lambent, scintillant green,” and cell-phones ring “like stranded birds.” The spring sun leaps out “hot and wet, like some jungle animal close and panting, blood on its lips and teeth,” the stars are “senescent and receding,” and the sea’s “turquoise and ultramarine, cobalt and indigo, like a field of violets and irises churning.”

There’s plenty of music history here too, from Dulan’s Sugar Factory performance venue to the apparently stupendous Betel Nut Brothers’ concert there in 2004 that, paradoxically, led to the author’s problems with the police. There’s also a wonderful description of a two-week hike into the high mountains to visit the sites of ancestral villages from which the Bunun had been forcibly removed by the Japanese almost a century earlier.

Most outsiders who hear the Siren song of the Bohemian life have personal motives for adopting it, but none is immediately apparent in this book, other than a desire to find fulfillment. What can be said is that such people are rarely happy to remain Bohemians for ever, or indeed for long (Ezell says he “couldn’t imagine being buried here”). If they end up combining elements of their new life-style with their older interests then they’re lucky indeed, and this Scott Ezell appears to have accomplished.

Bohemian attitudes usually include vegetarianism and pacifism. There isn’t much evidence of the former here, though Ezell does lament the excess of hunting on his trip into the mountains. Of the latter, he meditates at one point on his American-ness, evoking “US-backed assassinations and coups” and “drone strikes, shooting robot bombs into villages.”

This book is sure to become a classic English-language book about Taiwan. Ezell has the ability to evoke Aboriginal life even within its contemporary, often degraded context. He sees the poetry behind the plastic, as well as the eternal behind the transitory. The poet within him co-exists triumphantly with the cool observer, and you also immediately understand why he has so many friends in the area.

The book ends with three deaths, but Ezell is equal to them. He sees life as a series of cyclic renewals, as well as of usurpations of one culture by another that are endless, unavoidable, and not necessarily to be lamented. But in the short term he immortalizes individuals who might be thought to have little claim to immortality of any kind. This kind of awareness is found in some of the finest books, and one of several reasons why A Far Corner is so magnificent, and so richly deserving of classic status.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the