When the Sunflower movement started, I was in Toronto giving a seminar and teaching a class on President Ma Ying-jeou’s (馬英九) government reform of Taiwan’s history textbooks. I was about to leave my hotel for the university to give the last seminar, when I received a text message from Taiwan telling me that students opposing a trade deal with China had just stormed the Legislative Yuan.

I instantly thought: Am I like Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙), about to miss the beginning of a revolution? My plane was leaving that night, which means that I would arrive on the second day. Will police have cleared the site by then? But, of course, I was no Sun Yat-sen, having inspired no revolution.

GAME CHANGER

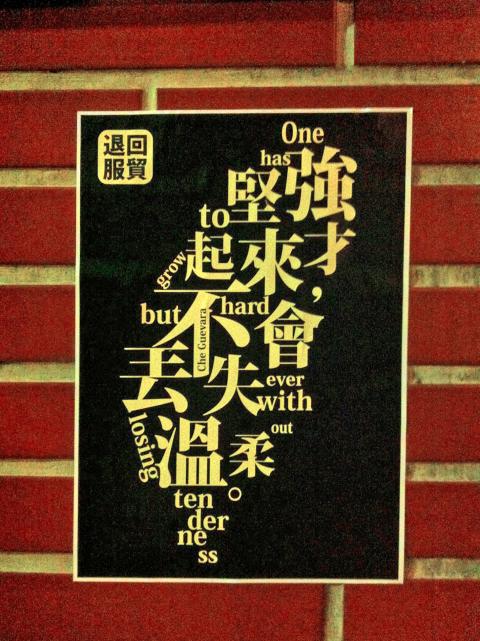

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The astonished audience in Toronto discussed the occupation as it unfolded in real time — something even up to a decade ago was unthinkable in a venue held so far way from the field.

Information technology has changed not only the way people mobilize, but also how scholars document ourselves and reflect on events. No one can roll back such a significant development, however terrifying it might seem. Today, the amount of time some scholars and elected politicians spend on Facebook, blogs, Twitter and other social media, distracts them from reading, thinking and conducting interviews in the field, immersed for weeks and months in other people’s lives far away from our offices. And now, the movement was just about to unite the two, by giving a chance to so many scholars to spend nights and days with students on the ground. The core mission of scholars and politicians — to think slowly and wisely about our society, its problems, its reforms, its future — has become increasingly difficult. Reading books are now a luxury, but we now have to admit that fieldwork has been restructured in many ways by technology.

I arrived back in Taipei on the afternoon of day two of the occupation. Thanks, globalization. I do not particularly like you, but you did me a favor on that day.

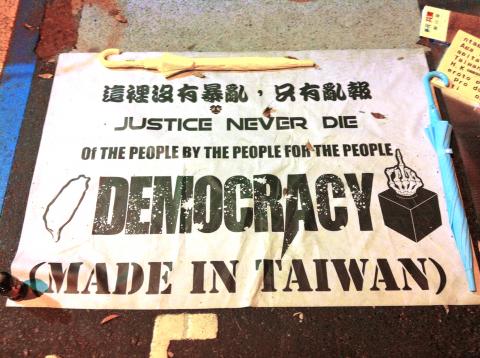

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The reason I wanted to return so quickly is obvious: Like other academics specializing in Taiwanese identity politics and geopolitics in the Taiwan Strait, I wanted to understand what was happening on the ground. Would it be a turning point? Would the government send in troops? Would China, whose rulers had repeatedly said for 20 years that political turmoil and major social instability in Taiwan would be a reason to intervene, remain silent or enter a new phase of relations?

Such questions were not meaningless. As we know, it turned out that the government did not send in the military (at least not into the legislature), China was shocked and in spite of its long standing menace, did not intervene. And yes, it was, from many respects, a turning point.

Before arriving back in Taipei, I couldn’t help but think that the storming of the legislature would instantly become a historical event. How come, as a scholar taking particular care in using words, could I consider an event as becoming instant history, as if it were instant noodles?

Photo: Stephane Corcuff

The storming of Taiwan’s legislature appeared to many as brave (it was) and unprecedented. But the fact is that it was neither unique, or a first. Indeed, each time a legislature is stormed, occupied, defended, shielded or burnt, by pro-democracy forces or anti-democracy ones (when we can distinguish them), it “makes history” because it reveals an impasse in dialogue between political forces. In many cases induces historical change. Storming and occupying a legislature, however brief, is not so rare in history, and each time it happens, it underlies the major significance of what a legislature is and what is at stake.

PRECEDENTS

Three historical events and memories came back to me before I landed in Taiwan last March. The first, in 1993, the shelling of Moscow’s parliament, in the midst of the conflict between Boris Yeltsin and the undemocratic Russian Federation’s Supreme Soviet. I was amazed at this black building called the White House, exploding on its right side by the shelling of Yeltsin forces — in the name of democracy. In 2011, hundreds of militants stormed the parliament of Kuwait, demanding the resignation of Sheikh Nasser al-Mohammad al-Sabah, who indeed later resigned as prime minister. Was that the start of a huge movement in the Arab world?

In January and February 1997, Bulgaria made world headlines — a rare event — when thousands of protesters laid siege to the parliament, while the country was under hyperinflation, and asking for the government to resign. The protests were led by students.

After a few days, I realized that these events had in fact been quite frequent in history, especially in recent years, though each time happening in different contexts, with different groups, different ideologies, different aims. Many more examples could be found both recently and in earlier times: Burkina Faso in October 2014, Iran in 1908, Serbia in 2000, Canada in 1849. There are, however, major differences: the Taiwan occupation was apparently unique in being long, non-violent, massive and ending peacefully, compared to other national experiences.

THE TAIWAN DIFFERENCE

Storming the legislature was described as an extreme measure by both sides — on one side to denounce the non-respect of representative democracy; on the other, to denounce a “bird-cage democracy” in Taiwan that would lead students to this “last-resort” means to have their voices heard. But, if we bear in mind the existence of so many precedents, occupation of the houses of government are a regular occurrence in the course of democratic development and consolidation, since a perfect and satisfactory representative democracy remains an ideal pretty much everywhere.

And what is legal is not necessarily democratic, just as something which is technically illegal is not necessarily undemocratic. Violence is obviously a sign of failure in discussion and negotiations. But the use of the words “symbolic violence” to qualify a breach of representative democracy is a double-edged sword, as the meaning of the phrase (A necessary evil? A dangerous act?) depends heavily on the political ideology of the one who uses it.

On day two, my field work could start: observing, asking rare questions, mainly listening to what people had to say, taking pictures (lots of pictures), collecting leaflets. And, many more days before the student movement announced its dissolution, thinking about the question: How to collect those historical memories? To the students I met there, and who were sensitive to this question (most were not until the very last moment, after the dissolution was announced), I asked: “We have pictures of the Tiananmen protests and of the Wild Lily movement, but where are the artifacts? Almost none are left.”

If the Sunflower movement belongs to Taiwanese and their history, we as scholars, had a responsibility to collect these visual traces — leaflets, banners, stickers, works of art, posters and so on. So that, regardless of the ideology of future researchers, and hopefully they’ll remain neutral, they will be able to study, display and share those artifacts that made history.

Stephane Corcuff is an associate professor of political science at the university of Lyon, and a researcher at the French Center for the Study of Contemporary China in Taipei.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she