Unusual things started to happen after Huang Teng-da (黃騰達) sold an apartment close to the Dongmen MRT station (東門) in Taipei following the murder-suicide of the family living there.

The buyer, citing a “premonition” about the apartment, backed out of the contract and, unusually for an investor, “didn’t balk at paying a penalty,” Huang says.

The prospective buyer probably got off easy. Following the attempted sale, the original owner was abused by her husband and her career suffered setbacks.

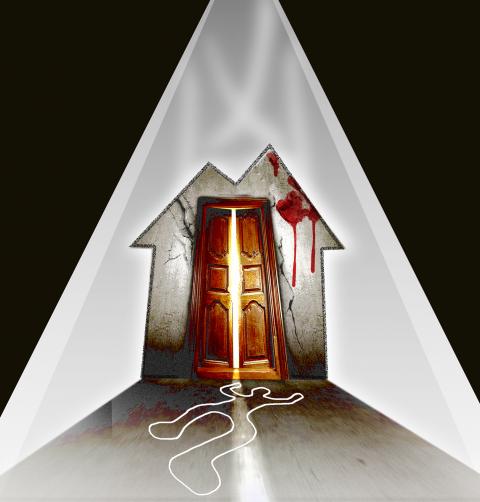

Illustration: Y. C. Chen

Soon after, Huang himself was afflicted by career difficulties and poor health. Though the symptoms of his misery are vague, the former real estate agent is certain of the cause: he had sold a xiongzhai (凶宅).

Huang immediately quit his job and left Taipei.

MALEVOLENT SPIRITS

Xiongzhai are variously translated as unlucky houses, inauspicious abodes, violent houses, murder houses and suicide houses.

They differ from haunted houses in that they become cursed exclusively because of the violent manner of the person’s death: murder or tragic suicide.

Marc Moskowitz, an anthropologist who has studied Taiwan’s spirit beliefs, says that the spirit “would almost certainly be malevolent.”

“Ghosts behave exactly like living people would,” he says. “To be angered at one’s own murder, especially if that murder was traumatic, would be a very rational worldview in a society that believes in ghosts,” he says.

Read: revenge on the living.

As in any society, Taiwanese believe in the existence of ghosts — the only difference being, perhaps, the degree of the belief and that it’s a ritualized part of daily life.

A recent poll by 360d Human Resources Consultancy Co showed that 87 percent of office workers believe in ghosts, with 48 percent consulting spirits for advice on love and career. Consequently, much time and money is expended on appeasing these spirits so as to avoid misfortune.

During Ghost Month, the prevailing belief holds that the doors of hell open and phantoms roam the streets trying to attach themselves to the living.

To avoid this bit of bad luck, you will see people, small business and corporate enterprise making offerings — snacks, fruit, liquor, meat — on makeshift tables and burning “ghost money” as bribes to appease these “good brothers” (好兄弟, a euphemism positively stated so as not to offend them), before these wandering phantoms return to the netherworld — hopefully satiated — for another year.

Ghost month, needless to say, is not a time to buy property, xiongzhai or otherwise.

Propitiating dead spirits can occur surreptitiously. Following Cheng Chieh’s (鄭捷) killing spree inside Mass Rapid Transit cars close to the Jiangzicui station (江子翠) at the end of May, 20 Taoist priests from Zhinan Temple (指南宮) volunteered to perform an eight-and-a-half-hour spiritual cleansing on the defiled carriages.

Allen Zhan (張玉人), a spokesperson for the Taipei Rapid Transit Corp (TRTC), says this was in response to requests made by close to 1,000 people.

“These rituals bring peace to the victims as well as to passengers,” he tells Taipei Times.

The ceremony, it is believed, mollifies the ghosts of the deceased and offers solace to the living, which can be brought about because it is a public, rather than private, gesture of observance.

But there is no chance of appeasing the ghost of a victim of suicide or murder in a private residence because it “crosses the border into family life in a very personal way,” Moskowitz says.

“It also points to the creepy factor. On a psychological level it is just harder for us to feel comfortable with violence that has taken place within the home because it is a reminder that there are malevolent forces or people who have been able to breach that boundary before,” he says.

So pervasive is the belief that these malevolent phantoms are out to harm residents, prospective property sellers are legally bound to inform buyers of a xiongzhai’s grisly history.

CAVEAT EMPTOR

When a home becomes a xiongzhai, its value plummets by at least 30 percent, Huang says.

This is a boon for the tiny number of investors who aren’t concerned about being contaminated with the taboo and buy them up and turn them into rental apartments. (There is no legal obligation to inform tenants of the apartment’s background.)

But for everyone else, the sudden depreciation in the value of the property is a disaster, and has led to some unscrupulous behavior by homeowners.

Examples abound where buyers file a criminal or civil lawsuit against the sellers of these houses. And in some cases, it’s both.

In a 2009 case, Lee Chiong-chi (李炯祺) was sentenced to an eight-month prison term after a man surnamed Chang (張) proved that Lee intentionally and deceptively sold him a xiongzhai, according to a report in the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper).

The Banciao District Court also ordered Lee to take back the property and return Chang’s investment.

Property buyers have become so concerned that they will be cheated by sellers that in 2011 Sinyi Realty Inc (信義房屋), Taiwan’s largest realty company, unveiled what it claimed to be the world’s first “xiongzhai peace of mind guarantee” (凶宅安心保障服務 ) — an assurance that any property they list is not a xiongzhai.

In its press release, the realty company cited Ministry of the Interior statistics that showed 20,992 people had committed suicide between 2006 and 2010, with 5,069 murders taking place over the same period.

“The xiongzhai occurrence rate is growing,” the company said in its press release.

“When a customer buys a xiongzhai, there is absolutely nothing you can do to console them,” says Jeremy Shive (薛健平 ), Sinyi’s general manager.

HEARTLESS HOMEOWNERS

If investors worry about unintentionally buying a xiongzhai, homeowners are deathly afraid that their homes will become one, not only because of the fear of having a malevolent presence but also because of how it will affect the value of the house.

It’s a fear that has led to some pretty callous conduct.

In June of last year, a man surnamed Huang (黃) jumped from the 12th floor apartment of one building and landed on the roof of another building eight stories below, the Chinese-language Want Daily reported from Keelung.

As the man lay dying, emergency response was unable to help him because the only access to the roof — considered public space under the law — was through a private apartment, which the homeowner’s son adamantly refused to allow.

He feared that the man might die, or worse, may have already been dead, and that its spirit would contaminate the residence.

Obstructing official duties, the report reminded the reader, is an offense under the Criminal Code.

“Please, a person’s life is at stake,” pleaded a police officer, according to the report. “Show some compassion and help out.”

He didn’t.

Emergency personnel were eventually forced to call in an aerial ladder truck to remove the man from the roof, a process that took over 40 minutes. He was pronounced dead later at hospital.

No charges were filed against the homeowner’s son in that case.

But charges might be filed against the owner of an apartment in Greater Kaohsiung, surnamed Cheng (鄭), who refused to allow police into his apartment last month following the suicide of a 75-year old depressed man surnamed Chiang (江), according to a report in the Liberty Times.

Chiang leaped from the balcony of his 12th floor apartment and landed on the fourth floor terrace of an apartment below owned by Cheng.

As with the roof in Keelung, the terrace in this case is also considered public space but only the owner of the residence it’s attached to can gain access to it from within the building.

When the authorities contacted Cheng, who lives abroad, he refused to allow them into his apartment to retrieve the body.

As rain poured down on the corpse for five hours, and with Chiang’s grieving family looking on, the police asked the Greater Kaohsiung District Prosecutors Office for permission to call in an aerial ladder truck to take the body away, which it granted.

The entire process took nine hours.

Exasperated police later argued that there was a tiny possibility that the man might have still been alive when he was first discovered. Had they been granted access to him, they might have gotten him through the house before he expired.

And even if he had died, they added, the body could have been extracted before the ghost of the deceased passed beyond the gates of hell.

It’s an interesting logic, but as Huang Chien-chien (黃千千) wrote in the comments section of the story’s online version: “If this happened in your house, most of you would probably have done the same thing” — the kind of thinking that most homeowners would agree with.

POPULAR CULTURE

The belief in ghosts has been an inseparable part of Taiwanese culture since Han Chinese began migrating here from China centuries ago, bringing with them the three millennia-old belief in spirits, ghosts and phantoms.

Only recently, however, has the idea of xiongzhai worked its way into the popular imagination, fueled by Web sites that list them, apps that denote their location, movies that depict them, songs sung about them and television programs that deconstruct them.

The media’s endless thirst for gore and the salacious coverage of it maintains editorial interest in them as well.

One Web site called J2H (凶宅網, www.j2h.net) provides a constantly updated list of known xiongzhai in all of Taiwan’s cities and counties, complete with details describing how the property came to be a xiongzhai as well as directions to its precise location.

So too does Unlucky House (台灣凶宅網, www.unluckyhouse.com), which also provides an online forum for “concerned” netizens to ask questions about properties that they might be interested in buying.

One forum member tagged xup6g4m4 responds to a question about the number of xiongzhai in New Taipei City’s Banciao District (板橋區), providing the addresses to 54 separate residences (one part of which is removed for privacy reasons, though they are easy enough to find), while another person in the same thread says that “Banciao has a lot of xiongzhai, so be sure to consult a real estate agent.”

The total number of Taiwan’s xiongzhai is unknown.

Many of the posts on Unlucky House are links to articles published by Apple Daily’s xiongzhaidaka (凶宅打卡, “Xiongzhai Check-in”), a column that has in-depth profiles of famous and infamous xiongzhai cases dating back decades.

It adheres to a strict format that starts with a textual description of the case, followed by (often grisly) photos of the scene and a Google map showing its location.

A week after the MRT massacre close to the Jiangzicui station, the column reported on the four decade-old murder of Chang Ming-fong (張明鳳) by Lin Hsien-kun (林憲坤) that took place in the same neighborhood.

It explained the circumstances of the murder — the divorced Lin wanted a sexual encounter with an accountant and lured Chang to his apartment where he sexually assaulted her and killed her — and a detailed description of how he “dismembered the body with a knife, cut off the head and the four limbs and cut the torso into eight pieces, stuffed the different parts into bags, which he then dumped under the Zhongxing Bridge and Fuhe Bridge.”

Below the article, several photos depict Chang when she was alive, her dismembered body, where it was found, the suspect being paraded in front of the media, the room where the murder took place, the building where the room is located and the street where the building can be found, along with its Google maps location.

CTV’s 52nd Law Court (第52法庭) also had a 10-minute segment on it.

The privacy of local residents and the family of the deceased seem to take a back seat to the public’s presumed right to know about which buildings are xiongzhai.

“The neighbors will single it out and people will refuse to live there, especially if there has been a homicide there,” Huang says.

Huang says that three years on he still “feels as if I’m influenced [by the ghosts] and there are minor health issues.”

But it also seems that things are looking up. Huang recently passed the civil servant examination and works in Miaoli.

When asked if he would ever sell a xiongzhai again, Huang responds without hesitation.

“Certainly not.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of