Rose, Rose, I Love You (玫瑰玫瑰我愛你) takes place in the late 1960s. In China, Mao Zedong (毛澤東) is overseeing the Cultural Revolution. Meanwhile in Hualien County, a coastal village is busy with a little cultural revolution of its own. Upon discovering that American GIs are about to dock for rest and recuperation from the Vietnam War, the enterprising owners of four brothels rush to build a modern bar and to teach their prostitutes to make conversation in English.

But what begins as a simple plan to teach three phrases scales up wildly in proportion when Dong Si-wen (董斯文), a high-school English teacher, is appointed to teach the crash course for bar girls. Determined that the soldiers not leave Taiwan with a poor impression, causing “a great loss of face for the nation,” Teacher Dong decides to include instruction in American culture, global etiquette, singing and dancing, points of law, the art of tending bar and Christian prayers (“since all GIs are Christians” and probably need comforting), leading 50 bewildered prostitutes on a costly adventure.

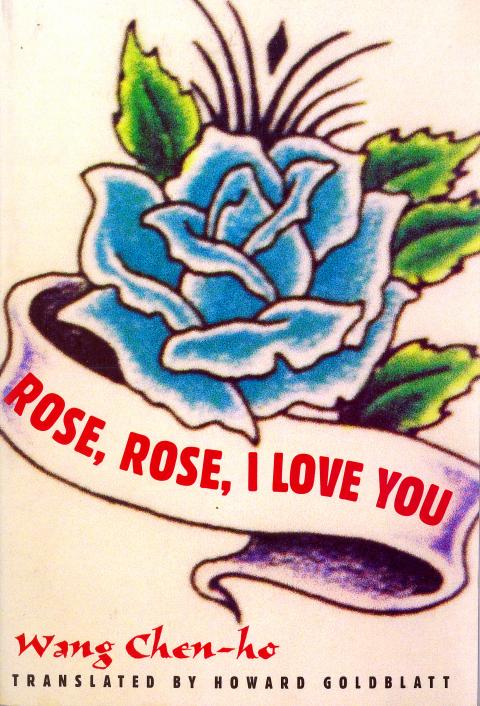

Originally published in Chinese in 1984, Rose, Rose, I Love You is the first work by Wang Chen-ho (王禎和) to be translated into English.

What makes Howard Goldblatt’s translation remarkable is that he’s able to smoothly reproduce much of Wang’s unusual dialogue, a blend of several languages.

The dialogue in Rose, Rose, I Love You mirrors the liminal state of language in Taiwan of the 1960s, which is right after Japanese colonialism but before Mandarin is fully adopted. Wang, whose characters use copious Hoklo (more commonly known as Taiwanese), peppers the novel with Minnan phrases like puichutchut (肥唧唧, “pleasingly plump”) and sainai (塞奶, “act petulantly”) and atoka (阿啄仔, “big-nose foreigners”). A-hen, a retired working girl, uses fragments of Japanese.

Goldblatt works gamely with Wang’s text, noting foreign words in italics so you can tell when Teacher Dong is trying to sound more refined by interspersing Mandarin with English (“Wonderful! Wonderful!”). He doesn’t always distinguish Hoklo words from Mandarin, but he cues beforehand when a passage of dialogue includes both. He also preserves most of the original wordplay, often by substituting parallel American phrases: The brothel owners know bopomofo (ㄅㄆㄇ), but pronounce it as “boar pour more” (補破網) in their Taiwanese accent. When Dong announces in English that they will conduct diplomacy “nation to nation, people to people,” the brothel owners hear it in Mandarin, the way Goldblatt renders it in brackets: “heart to heart, ass to ass” (內心對內心,屁股對屁股). His result is an English-language novel that successfully records language conflict in Taiwan, depicting how the way people speak declines to be subsumed under a single framework.

Rose, Rose, I Love You is also about the subversion of literary aesthetic.

Wang takes the device of epiphanies — which James Joyce uses to lead characters to great self-realization — and renders them as Teacher Dong’s “strokes of genius:” new ideas for the bar-girl crash course that only force the brothel owners to spend more money.

In two chapters, Wang applies the modernist technique of interior monologue. To present the day’s events, he uses the voice of brothel owner Big-Nose Lion and replicates Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in the final episode, Penelope, of Joyce’s Ulysses. But Big-Nose Lion is a burlesque parody: Molly is Joyce’s incarnate of the Great Mother, pure warmth and physicality, while Big-Nose Lion is a pimp who deals in the flesh. In Wang’s novel, Penelope — Molly’s mythical counterpart — is an English name that Teacher Dong later tries to bestow on one of the prostitutes, who derides it, “Aiyo! Whoever heard of an ugly name like Pian-ni-lao-mu [trick your old ma]?”

What emerges sounds like an acerbic rejection of the idea of uniform language or literary aesthetic: The text is like a hipster who tries on new clothes and makes them all look ironic.

It could also be a searching look at a protracted moment in Taiwan’s history — one extending to this day — of testing out many trappings of identity, often for the purpose of outside consumption. But the novel is open-ended, offering no glimpses of its true self: In the final scene, the prostitutes intone the Lord’s Prayer and Teacher Dong launches into a reverie: The Americans are coming, greeted by 50 world-class bar girls wearing cheongsams or eye-catching Aboriginal dress. The ladies sing the titular song, Rose, Rose, I Love You, first in Chinese and next in English. Each is a shimmering ambassador of an ethnic identity none wholly inhabits, and no one is so sure of who she is.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had