To form any trade agreement with China requires consideration on a raft of issues ranging from labor standards and environmental protection, to human rights. It also means admitting that China is ruled by oligarchs and plutocrats, has no regard for the rule of law and allows state-sponsored organ harvesting.

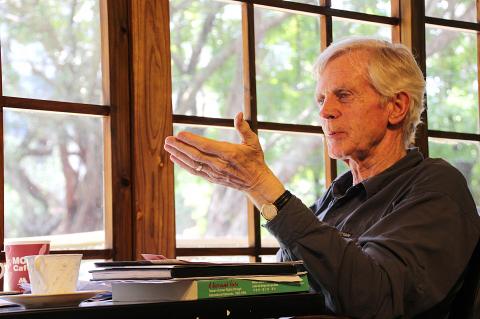

“I don‘t know why any rational person would want to [sign] an agreement with China in any matter… Personally, I wouldn’t even enter an agreement with China selling popcorn,” says David Kilgour, a former member of the Canadian parliament who is internationally known for his commitment to ending human rights abuses across the globe.

It was a message Kilgour delivered during his visit to Taipei earlier this month. Having served as a member of parliament for 27 years, during which he did a stint as Secretary of State for Asia-Pacific between 2002 and 2003, the former politician has been a long-term observer of Taiwan’s democratization. To show his support for the Sunflower movement, Kilgour arrived on April 8, and immediately went to the then-occupied Legislative Yuan where he gave speeches outside and talked at length to protestors.

Photo courtesy of Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Foundation

Over the following days, he held several talks outside the legislative chamber and also paid a visit to former president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), who is said to be suffering deteriorating health in prison. The 73-year-old former politician says he no longer has to hold his tongue, and now only listens to his own conscience.

DEALING WITH CHINA

Kilgour’s moral sense has made him a firm opponent of what he calls China’s “robber-baron” communism, where there are “71 billionaires who are members of the National People’s Congress.”

Photo courtesy of Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Foundation

For Kilgour, human rights should always trump economic considerations, and he has little patience for companies such as Taiwan’s Foxconn, maker of Apple iPhones, that thrive off China’s lax labor laws.

Cheap consumer goods made from convict labor and sold across the US are equally problematic, he says. Kilgour cites Charles Lee, a follower of Falun Gong, a religious group that the Chinese government criminalized in 1999. Imprisoned from 2003 to 2006 for religious dissidence, Lee, along with other inmates, worked 16 hours a day without being paid and would be beaten if they refused to work.

Upon release, he returned to his home in the US where he discovered that the kind of Homer Simpson slippers he had made in prison could be bought, even though US federal law prohibits the importation of any products produced with convict labor.

Photo courtesy of Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Foundation

“New Zealand was proposing to have a free-trade agreement (FTA) with China in 2007. I remember talking to someone from the foreign ministry: ‘How do you keep forced labor products out of New Zealand?’ [The reply] ‘We are going to have an inspector in Beijing.’ I almost fell off my chair, laughing,” Kilgour says.

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY

Photo courtesy of Tsai Jui-yueh Dance Foundation

The persecution of Falun Gong in China is a subject Kilgour knows painfully well. In 2006, he and human rights attorney David Matas released a report that documented Beijing’s organ-harvesting atrocities perpetrated against practitioners of Falun Gong. Since Beijing outlawed the group, its followers have been incarcerated, and a large number of imprisoned practitioners have been executed, after which, the report shows, their internal organs are removed for sale to foreign nationals in need of transplants.

Kilgour, who worked as a prosecutor for 10 years, says they have gathered evidence that shows the widespread practice of organ harvesting. It includes the confession of the wife of a former surgeon. Now a resident of the US, the woman told Kilgour that between 2001 and 2003 her husband removed the corneas of around 2,000 imprisoned Falun Gong members. After the procedure, victims were sent to other operating rooms to have their liver, kidneys and other organs removed. The desecrated corpses were then thrown into the hospital’s boiler room.

In another case, a Taiwanese businessman interviewed in 2007 says he flew to the Shanghai No. 1 People’s Hospital in 2003 for a kidney transplant and went through eight antibody cross-matching tests before he found a matching pair. Hospitals keep a database of potential organ donors and once a match is made, “the victim, say in [forced-labor] camp No. 60, is dragged to the operating room, given light anesthetic,” and the organ is removed.

“Eight people were killed in the camp before he could get a kidney that worked,” he says.

In 2006, Huang Jiefu (黃潔夫), China’s former Deputy Minister of Health, publicly admitted that 90 percent of organs extracted from dead bodies came from executed prisoners in China, where there are 55 capital offenses including tax fraud. But, Kilgour says, the government there has never admitted “once that organs also come from Falun Gong practitioners.”

Aware that many of the claims cannot be independently verified and would be difficult to prove in a court of law, Kilgour still believes that there is enough credible evidence to draw international attention to the issue. Along with Matas, he has been to over 50 countries to raise awareness about the dubious state-orchestrated activities. For their efforts, the two were nominated in 2010 for the Nobel Peace Prize. Meanwhile, they are banned in Russia, after a court ruled that Bloody Harvest: the Killing of Falun Gong for their Organs, a book co-written by Kilgour and Matas, is a work of “terrorist literature.”

Needless to say, the two authors are not permitted to enter China to conduct their research. But this is probably a good thing, Kilgour says, because doing so might endanger the lives of Falun Gong practitioners.

He gives the example of a member of the religious group who disappeared after European Parliament Vice President Edward McMillan-Scott met with him in Beijing.

“He hasn’t been seen since. [McMillan-Scott] felt really terrible about this.”

Considering how it treats Falun Gong practitioners, countries should be extremely cautious when signing trade deals with China, Kilgour says.

“Why does anyone in Taiwan think that … China would show respect for the terms of that agreement?” he asks.

It took the Canadian government 18 years to conclude negotiations on the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA) with China, but has yet to ratify it as “there has been so much opposition,” he says. The retired politician also thinks that strong opposition will prevent his country from forming a FTA with China’s unelected leaders.

SUNFLOWER MOVEMENT

Kilgour says the student-led Sunflower movement has stiffened the resolve of democrats throughout the world, and that as a long-term observer of democracies, he could only think of Sofia, Bulgaria in 1997, when anti-government protestors stormed the parliament building where Kilgour happened to be at that time.

“But I don’t think it has ever happened anywhere else with that kind of restraint, dignity and respect that people have for each other.”

However, as the judiciary is increasingly used to silence critics of the Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) administration, Kilgour expresses his concerns for students and activists now facing prosecution for occupying the legislature, stressing that their action is “in the interest of greater justice.”

“Democracy is a vigorous and messy thing. One of the people [who occupied the legislature] may one day become premier,” he says.

For Kilgour and many of his former colleagues in the Canadian parliament, Taiwan is an independent, sovereign state, but most of them think that “if they make too much noise Canada’s trade with China will suffer.”

Kilgour recalls a trip to Taiwan he took when he was secretary of state for the Asia-Pacific.

“I got a call from the Chinese embassy, saying ‘Mr. Kilgour, if you go to Taiwan, you will set back relations between China and Canada significantly, and we strongly urge you not to go.’ Of course, nothing happened.”

Still, the cruel reality is that as long as China remains a dictatorship, Kilgour says, it will bar Taiwan from joining the international community.

“Taiwan will become a member of the UN five minutes after China becomes a democracy… Each one of you [in Taiwan] has to do what you can to promote democracy in China,” he says.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has