Outstanding books are easy to review, as are really bad ones. Those that lie somewhere in between present a more difficult challenge.

The 228 Legacy is a first novel by Jennifer Chow, a young Chinese American. It’s set in 1980s California, in the small town of Fairview. Despite the title, no part of the book takes place in 1947, and only a few pages are set in Taiwan.

The novel’s main characters are Lisa, an administrative worker in an old-people’s home when the novel opens, her school-age daughter Abbey, and her mother Silk, who has worked in the Californian wine industry. A fourth character, Jack, of a similar age to Silk, works as a school janitor.

These four have chapters dedicated to them in an almost strict sequence. And the whole novel is narrated in the present tense.

All these characters are of Asian ethnicity. Silk was born and married in Taiwan, while her daughter and grand-daughter are both full-fledged Americans. Jack, by contrast, was born in China, and this initially causes some dissention. He tries to befriend Silk, in particular, but his overtures are haughtily rejected. The old lady is passionate about her Taiwanese identity, which is hardly surprising, because her husband, an academic chemist, was, it soon transpires, murdered by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) during the uprising on Feb. 28, 1947.

To begin with, however, the characters’ problems are far removed from Taiwan’s history. Abbey feels isolated at school, despite sharing top place in all math tests with another high-aspiring student. Lisa loses her job on the first page, while midway through the novel Silk is diagnosed with inoperable cancer.

There’s in fact plenty about old age, illness and death in this novel — in part, we’re told, because of the author’s experience in geriatric social work. This nevertheless contributes to the book’s somewhat gloomy ambience. When Jack falls from a ladder and breaks his leg you can’t help thinking it’s something only to be expected in this particular novel.

The main reason I found this book rather depressing, though, wasn’t the geriatric and sickness emphasis but the story’s unrelenting small-town ambience. There’s nothing wrong with small towns as such, of course, but for me what ennobles life is the grandness of wild nature, the greatness of great books and music, and relations — passionate, intellectual or just plain comic — with other people. And no character in The 228 Legacy touches, in any significant way, any of these things. They’re all happy to remain for the most part in a world defined by receptionists’ offices, school-rooms, convenience stores and dining rooms.

The characters in Chekhov’s plays also live in relative backwaters, and for the most part, like Jennifer Chow’s characters, don’t engage in discussions of philosophical issues either. But their imaginative worlds extend far beyond those in this novel, and Chekhov’s insights into their personalities are infinitely richer than those on offer here.

This small-town mentality extends beyond Fairview, California, too. When Silk goes on a trip to Rome, one of the most culturally rich places on the planet, you’d have thought, among the few impressions she comes up with is that they make pizza better in Italy than they do in the US. It isn’t too surprising, then, that her reactions to Taiwan are similarly limited.

As the main reason any reader in Taiwan is likely to pick up this novel is the reference to the 228 Incident in the title, it’s appropriate to take a closer look at the references to Taiwan within the text.

There’s a mention of piles of severed heads on the streets in 1947, the cruelty of KMT soldiers, and the severe food shortages under the party’s early rule. When Silk, Lisa and Abbey travel to Taiwan on a three-day sightseeing tour, they visit the National Palace Museum, the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, Yangmingshan and Greater Kaohsiung, where they find a 228 memorial. Silk laments that the National Palace Museum contains Chinese treasures, not Taiwanese ones, and in Kaohsiung they gather some of the “rich chocolate earth” to take back to the US.

What are the book’s virtues, then? Clearly imagined detail, consistent characterization and avoidance of bombast must rate highly. In essence this is what some people would call a heartwarming read — taking account of suffering but coming up with a reasonably optimistic reaction to it.

At its center, however, this book appears to propose that by the uncovering of secrets rooted in the past, the present can be made more tolerant and cooperative. Silk, for example, considers her cancer the result of long-suppressed anxiety about her husband’s death. If the virtue of speaking freely about the past is this novel’s thesis, then it’s doubtful if it’s fully realized. We learn the basics of the 228 story quite early on, and its unmasking doesn’t really lead to any great improvement in the characters’ lives. Silk eventually dies, Abbey predictably gets over her school-days problems, and Lisa and Jack find their own ways forward, Jack making a memorial garden for Silk and becoming a sort of substitute father for Lisa. This is all just what you’d expect, barring catastrophes, of almost any lives.

All in all, then, this novel serves as a minor educative experience for those who’ve never heard of 228, and have only vague ideas about Taiwan. For those averagely well-informed on both topics already, however, there’s relatively little to be gained from it.

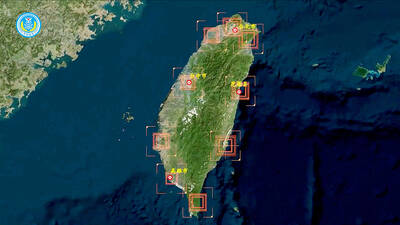

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On