Back in 2009, the New York Times published an article headlined “Recyclers, Scientists Probe Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” which noted that a group of scientists had “set sail from San Francisco Bay ... to study the planet’s largest known floating garbage dump, about 1,000 miles north of Hawaii.”

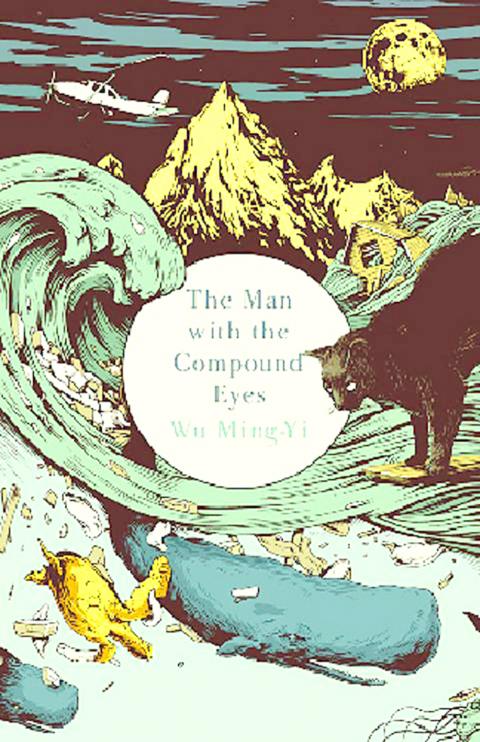

Fast forward to 2013: Taiwanese nature writer Wu Ming-yi (吳明益) has just released an English translation of his The Man with the Compound Eyes (複眼人) that’s aimed at an international readership. The 300-page novel, which has an eye-catching cover for the new British edition, is about that same floating dump.

Wu started writing the novel in 2006 when he read about the floating trash vortex in Chinese-language newspapers. As novelists often do, he concocted a “vision” based on the vortex: An Aboriginal teenager from the imaginary island of Wayo Wayo rides this garbage island and washes up with it one day on the east coast of Taiwan. In the ensuing chaos, the Taiwanese print and TV media have a field day reporting this ecological calamity, and Taiwan — the story is set in the near future of 2020 — is never the same.

In many ways, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a Pacific novel, about a Pacific Islander identity that differs in many ways from the commonplace Han Chinese-centric novels that are published in Taiwan.

The novel stars the boy from Wayo Wayo and a middle-aged Taiwanese college professor named Alice, both of whom are thrown into Taiwan’s east coast wilderness in a search for some lost hikers -- and enlightenment. There’s a cast of characters that expats will know well from their travels along the east coast, and Wu plots the story in very Taiwanese terms. (The English translation by Canadian expat Darryl Sterk, a professor at National Taiwan University, is superb and sensitively captures the nuances of Taiwan’s Aboriginal cultures and languages.)

Wu’s rollercoaster of a story is about wilderness, wildness, wonderment, love. It’s also about “massage parlors” along the east coast where tired and drunk soldiers go for rest and relaxation, with mini-lessons thrown in about various aspects of Aboriginal culture and food.

For readers in Taiwan who have been here for a number of years and know the east coast well, Wu’s novel is sure to strike a chord. But just how this Pacific novel will do overseas with readers in Europe and North America who know little about Taiwan or the Aboriginal cultures here remains to be seen.

As a longtime expat in Taiwan, I read the novel as a critique of modern society’s disregard for our planet’s ecology and environment — a wake-up call, in other words, for Taiwan and the rest of the world.

Readers overseas might find Wu’s story merely a pleasant diversion from the daily grind. You may not have to know much about Taiwan or insect eye biology to enjoy The Man with the Compound Eyes, and the mid-book chapters about that reveal the mystery behind the man with the compound eyes are perhaps the best writing to ever come out of a Taiwan novel. Some readers have drawn comparisons between the novel and Yann Martel’s Life of Pi. Yes, it’s that kind of book, and it would make that kind of movie, too.

Wu’s work began its literary life as a mostly-neglected, unheralded Chinese-language novel in 2011. Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (國立台灣文學館) used their resources and contacts to help set the book on its way to translation and overseas publication.

Published by Harvill Secker in London last month, the book will be released in New York in 2014, with a French edition as well. The US edition of the book, for reasons that only publishing and marketing industry executives know for sure, will not be released until next year. Readers in Taiwan and elsewhere who want to order the book can use the British Amazon Web site to purchase the UK edition.

Once I started reading this edition, I couldn’t put it down, and over the course of several days I felt that I had ventured into a new, uncharted territory concocted by a Taipei visionary. Part South American magical realism, part Margaret Atwood rollercoaster of the imagination, The Man with the Compound Eyes is a wild story that’s been mashed up into art, and you don’t need compound eyes to appreciate its unique vision.

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000