This collection of eight short stories by the author of I Love Dollars [reviewed in the Taipei Times Feb. 11, 2007] poses several problems, not the least of which is that it takes a considerable degree of determination to struggle through it.

In one way, this is strange. All the stories are tightly constructed, and the English translation, by Julia Lovell, is quite exceptionally fluent. Zhu Wen’s (朱文) wit and outspokenness are undiminished. I nevertheless felt an unease while reading the book that has taken me some time to account for.

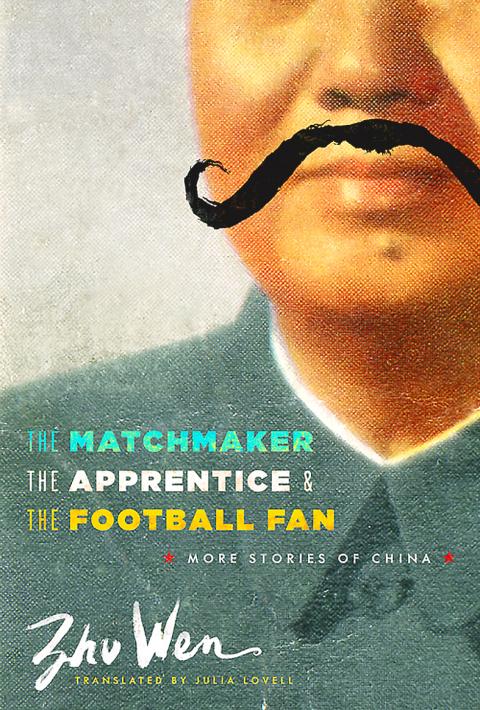

The title story of I Love Dollars was characterized by a rampant sexuality and absurdity. The volume’s other stories contributed to the portrayal of China as a country that was far gone in the process of losing its way in a maze of commercialism. Seven years on, the publishers at Columbia University Press call the stories in The Matchmaker, The Apprentice, and The Football Fan “socialist gothic,” and describe Zhu as a “fearless commentator on contemporary China.”

The problem with this last claim is that all these stories bar one were published in Chinese in the 1990s. (The final story, The Wharf, came out in 2009). China has changed a lot since then. Nor is this all. Another trouble with the assertion is that Zhu appears to have given up writing fiction, and now devotes his energies largely to film-making.

Da Ma’s Way of Talking opens the new volume. It’s a somewhat slight tale of a young man (the narrators of all the stories except two are young men) who is driven mad by discovering that a string of his friends, including his girlfriend, talk in the manner of a former student he’d known but that the others couldn’t possibly have met. It transpires the student in question was killed on the road to Tibet, but for the rest the mystery is nowhere satisfactorily explained.

The Matchmaker follows, the story of another young man looking for a girlfriend while conducting an affair with a married woman. An unusual feature is that their relationship is characterized by protracted quotations from Hamlet, made absurd by the actor being represented as continually smoking cigarettes. Smoking is one of Zhu’s obsessions.

Next comes The Apprentice, an ironic and hard-hitting account, scatological in places, of someone starting work in a factory where his co-workers are given to swearing, drinking and cursing the leadership of both the factory and the country as a whole. They’re also addicted to table-tennis and playing cards, two forms of passing the time that lead to the story’s absurdist plot-resolution.

What I found myself thinking while reading these and later tales was that, while they were clearly intended to be comic, and surely were comic in their original Chinese when read by citizens of the 1990s PRC, I was not doubling over with laughter. But I don’t expect Michael Moore or Will Self are particularly funny in Chinese either. Of all literary genres, comedy seems to me the one that travels the least well.

On the other hand, I Love Dollars was funny enough. So if comedy can indeed travel in the right circumstances, and Zhu’s comedy at that, how are we to explain the relative plainness of this new collection? The obvious answer is that the author no longer has his heart in the story-telling business.

A pointer to this conclusion is that this time translator Julia Lovell provides no introduction. Her introduction to I Love Dollars was outstanding, but this time she prefers to say nothing. Maybe she feels that she’s said it all before, but it’s also possible she senses these stories are less good and prefers to keep her mouth shut. She’s a lecturer in modern Chinese history in the University of London, and readers will perhaps remember that she is author in her own right of The Opium War, reviewed in the Taipei Times on Oct. 2, 2011.

A further indication of this book’s relative shortcomings is that the great Chinese scholar Jonathan Spence, who provides an endorsement, says that these stories are “both darker and denser” than those in Zhu’s first book. This could be a coded way of getting round the undoubted fact that they are simply less funny.

The story Spence chooses as memorable is Mr. Hu, Are You Coming Out to Play Basketball This Afternoon? This is a very clever plot-driven tale about a man who adopts the child of a woman he once found very attractive. What finally occurs can perhaps be guessed, but the story is told without hint of censure, and is indeed something in the way of a small masterpiece.

Other items include Reeducation, an extended political satire set in the years after the Tiananmen Square Massacre of June 1989, the bleak and formal The Football Fan about a youth who claims to be both gay and a small-time thief — all the six sections of which begin with the identical paragraph — and The Wharf, set in Tibet and featuring the indigenous Zangxiang breed of pigs.

This leaves only Xiao Liu, a rather convoluted but nevertheless major story. It has two thematic parts, one set in Harbin and featuring the narrator’s obsession with a woman of partly Russian ancestry, the other set in Nanjing and involving the aforesaid Xiao Liu who’s both a suspected spy on the narrator’s Fujian-dialect-speaking mother, and a computer freak and genuinely good friend of the family. This kind of paradox is quintessential Zhu. He probably thinks that being both a writer and a film director is equally paradoxical, but delights in the situation nonetheless. Should he read this less-than-rave review, he’ll probably take it with a laugh and quick aside on the essential absurdity of the non-Chinese-speaking world — not to mention the Chinese-speaking one as well.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has