In an abandoned factory, a scavenger rummages through piles of junk, digging out worker IDs and faded slogans, among other worthless things. Nearby, inhabitants of a destitute neighborhood eke out a living by finding and selling scrap iron, planks of wood and other reusable waste, while the threat of demolition looms over the entire community.

These are the everyday scenes that Chinese director Wang Bing (王兵) captures in Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (鐵西區), a meticulously crafted epic documentary about the slow demise of a factory town in China’s northeastern city of Shenyang. Upon its debut at international film festivals in 2003, the nine-hour trilogy immediately garnered high critical acclaim, and in the following decade, Wang has grown to become a leading figure of Chinese independent film, with an ever-expanding oeuvre that contains Fengming: a Chinese Memoir (和鳳鳴, 2007), a formally daring first-person narration of the worst of Maoist China, and Venice-winning Three Sisters (三姊妹), which follows the impoverished lives of three girls in a mountainous village in Yunnan.

Wang was in Taipei earlier this month to attend the Taipei Film Festival (台北電影節), which screened several of his works. Intellectually lucid and outspoken, Wang shared his thoughts on cinema and his experiences as an independent filmmaker in China. Working exclusively in digital format and outside the film industry, Wang says his works are mostly circulated within his country through pirated DVDs, with no chance of distribution.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

“I don’t know who sees my work or how they respond to it. I no longer think of these questions. What matters to me is to be able to make films,” Wang says.

Emergence of a digital auteur

In 1999, Wang entered the Teixi District of Shenyang, China’s largest industrial base. With nothing but a small rented DV camera, he started to film the region’s complexes of factories and railways, and the people who worked and lived in the area. He didn’t have enough money to buy DV tapes, which cost the equivalent of NT$400 each. “I used one tape a day. Back then, my monthly living expenses were 300 yuan (NT$1,500),” the 45-year-old director recalls.

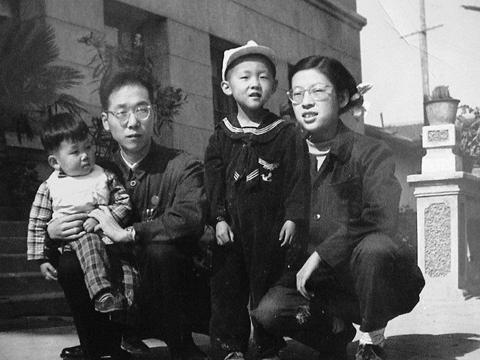

Photo courtesy of Wang Bing and Taipei Film Festival

He continued filming for 18 months.

The end result is an intimate masterpiece chronicling the area’s transformation from a major industrial hub made up of several hundred factories that employed over a million workers during the heyday of Chinese communism, to the crumbling ruins as China transitioned from a planned to a semi-market economy. The viewer comes to understand that human suffering is the price of progress.

While critics often laud the trilogy for capturing and preserving a rapidly vanishing world, Wang attributes much of its international success to its exploration of digital filmmaking rather than its content.

Photo courtesy of Wang Bing and Taipei Film Festival

“The story I chose, its enormity and the way it was shot, has the characteristics of digital cinema. The relation between digital filmmaking and people’s lives and how they unfold are different from traditional filmmaking,” he notes. “It just so happens that during the time I made this film, cinema had undergone the change from celluloid to digital.”

Using a handheld camera, Wang moves spontaneously with the inhabitants through their neighborhood, following people who happen to walk into his frame. Sometimes, the camera appears to be a plain object placed among household utensils. Indeed, the people Wang films feel so much at ease in front of the camera, they do not hesitate to bath naked in front of it.

The filmmaker, however, doesn’t believe that documentary filmmaking can adequately capture or reflect reality. For him, the relationship between the two doesn’t exist in practical terms.

Photo courtesy of Wang Bing and Taipei Film Festival

“Reality is a term used academically to discuss documentary cinema. It is a concept, a way of thinking about the world. To me, the so-called reality in documentary is nothing more than emotional truth, or to be truthful and respectful of the person or event depicted,” the director explains.

Recovering History

The recovery of history is central to Wang’s cinematic endeavors, and is driven by an urge to fill the void left by the nation’s collective amnesia of its past and the rapid disappearance of people, places and ways of life. After three years of interviews with more than 100 survivors which took him across China — from Shanghai and Guangzhou to Tianjin and Xinjiang — Wang completed his debut feature The Ditch (夾邊溝) in 2010. Based on Chinese writer Yang Xianhui’s (楊顯惠) book Goodbye Jiabiangou (夾邊溝記事), the film is a historically accurate account of the tragedy that happened at a labor camp located in Gansu Province’s Gobi Desert in 1960. It was a time when the nation was plagued by the widespread famine that came to be known as the Three Years of Great Chinese Famine (三年大饑荒, 1958 to 1961). Nearly 3,000 “rightists” were sent to the camp for re-education. Most of them starved to death. Only 300 people survived.

Photo courtesy of Wang Bing and Taipei Film Festival

Wang points out that as the making of historical drama often involves too much complexity for independent filmmakers to overcome, it is all the more important to realize the project when he has a chance.

“My parent’s generation couldn’t have made this kind of film. But I raised the money and made it the way I wanted. And though it was difficult to make the film with limited resources, it was particularly important to complete it,” he says.

Wang’s cinematic writing of history comes from personal experiences and perspectives. Grand historical viewpoints and discourses don’t interest him as they only frame and shape the way history is perceived, he says.

“To me, history is a moment of a person’s life which touches that person’s inner world in a profound way. It is not difficult to depict the macroscopic. But true history lies in one day, one hour, one moment of truth in someone’s life,” he muses. “In my documentaries, I don’t tell the whole story of a person; I portray a moment in its entirety.”

Fengming: a Chinese Memoir is an eloquent example of Wang’s approach. He Fengming (和鳳鳴), a retired journalist the director encountered while he researched the fictional project, is the sole heroine in the three-hour cinematic oral history that reveals He’s personal account of the anti-rightist campaign she barely survived. Her husband was among those who died at the labor camp of Jiabiangou.

Deceptively simple, the film opens with the elderly woman trudging up a pathway toward her flat, settling into a chair in the living room and speaking directly to the camera across a table as night gradually falls. The flow of her narrative carefully coincides with the changing light and the progression of time so as to create a still, almost sepulchral space where the elderly survivor seems to only exist in her own memory of the past, Wang says.

Savvy image-maker

Realism, says Wang, who graduated from the department of photography at Luxun Academy of Fine Arts (魯迅美術學院) and later furthered his cinematographic study at the Beijing Film Academy (北京電影學院), is never his goal.

“Elements like light and characters; some are concrete, some abstract and some allegorical or symbolic. How you combine all these elements in one shot at one fleeting moment defines your ability to see things,” Wang says.

“Film can never be a work of abstract painting. It always relies on realistic images to describe the abstract, to use the concrete to create psychological truth,” he adds.

Like Fengming: a Chinese Memoir, most of Wang’s films are commissioned by art festivals, museums and other cultural institutions abroad. In association with Arte, a Franco-German TV network, Three Sisters, Wang’s latest documentary, delivers an intimate portrait of three young sisters living in gripping poverty in a remote mountain village in Yunnan Province. With their father leaving for the city looking for work and their mother who ran off long ago, the children spend their days collecting dung, herding sheep and doing chores that seem endless.

More accessible than Wang’s previous works, the documentary has many of the director’s signature techniques. As always, the camera is perceived as a familiar part of life that people neither confront nor shy away from. Surprisingly, it only took Wang 12 days to film the children, their relatives and friends.

Wang says that the story of extreme poverty in rural Yunnan also marks a geographic shift in his films from the Yellow River basin, which covers the northern provinces of Shanxi, Henan and Shandong, to the Yangtze River basin, which extends from Qinghai, Anhui, Jiangsu to Shanghai.

“China is vast, and the stories and histories of different regions vary greatly. I made The Ditch because I wanted to tell the story of the Yellow River basin. Important Chinese historical events have taken place there … Chen Kaige (陳凱歌) and Zhang Yimou (張藝謀) have made many films about the area, but I don’t want to tell similar stories. I want to tell the story often omitted in Chinese culture,” the director says. “With the Yangtze River basin, where politics, the economy and people’s everyday life have experienced the most violent changes.”

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had