A debut feature by Chiu Li-kwan, a big shot in the entertainment business whose career spans nearly 30 years, David Loman brings back bawdy humor and grassroots comedy that have subsided after the heyday of stand-up comedian Chu Ko Liang (豬哥亮), who rose to superstardom and became a household name in the 1980s. Tailor-made for the now 66-year-old Liang, the movie is a well-executed work of entertainment highlighting off-color humor without compromising a solid story line.

Liang plays David Loman, a simple country bumpkin who accidentally becomes a big boss in the criminal underworld. A decade passes, and life seems to go on as usual — drinking tea, solving everyday problems for locals and receiving “protection fees” — until one day a deity tells David through a medium that he needs to find a double to avoid a catastrophe. Panicky, the boss seeks help from Old Ho, a fortune teller also played by Liang, who agrees to pass as David for a few days, but is assassinated when attending a gathering with fellow gangsters.

The mastermind behind the killing is Pinch Junior, played by funnyman Kang Kang (康康), the son of the late Boss Pinch, who passed his authority on to David 10 years previously.

Photo courtesy of Polyface Entertainment Media Group

Blaming David for his father’s death, Xiao Ho (Tony Yang, 楊祐寧) soon reconciles with the boss who vows to avenge Ho’s murder. They become apprentices to Silly Pork, played by veteran actor Chen Po-cheng (陳博正), a kung-fu warrior who used to be a bodyguard for former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝), and quickly masters the one-finger, martial-arts technique.

It doesn’t take long before David’s estranged daughter Jin (Amber Kuo, 郭采潔) finds out the truth and joins the team. Fighting bad guys at night, the three masked fighters win popularity among locals, and in the process, David is also able to make up for lost time and rebuild the father-daughter relationship with Jin.

The day of reckoning arrives when Pinch Junior holds a public memorial ceremony for his late father and declares his legitimacy as the rightful big boss.

Photo courtesy of Polyface Entertainment Media Group

Wearing a floral print shirt and wooden clogs, Liang thrives in the title role as a good-natured, foul-mouthed old man constantly hurling quips and risque jokes that often involve a fixation with the male and female sex organs. The film’s boisterous and boorish humor relies heavily on cleverly written wordplay in Mandarin, English and Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese). A good example can be found in the title of the movie, which is a phonetic translation of “underworld boss” in Hoklo.

While Liang’s untamed humor recalls the pre-feminist era, director Chiu updates her comedy with contemporary elements such as the syndicate using Facebook to boost its popularity. More interestingly, the conventions of kung-fu and superhero movies are borrowed to create a comic, satirical effect. The elegant moves of wing chun (詠春) are replaced by the one-finger technique which can be easily mastered by banging one’s finger with a hammer. And the much revered deity Guan Gong (關公) becomes an inspiration to the trio of homegrown superheroes and heroine. To director Chiu’s credit, no comic segment ever spins out of control or is disconnected from the rest of the movie, showing an all-too-rare ability to weave seemingly peripheral humor into a sensible whole.

Meanwhile, romance kindles between Kuo and Yang, who make a lovable on-screen couple, though the toothsome Yang looks nothing like a zhainan (宅男) — the Taiwanese equivalent of the Japanese otaku, or nerd — even wearing a pair of black-rimmed glasses. The movie is also delightfully supported by a string of cameos by actors and entertainers including actress Su Chu (素珠), Jeff Huang (黃立成), Ma Nien-hsien (馬念先) and Yin Wei-min (應蔚民), better known as Clipper Xiao Ying (夾子小應).

Photo courtesy of Polyface Entertainment Media Group

Fast-paced and packed with bawdy humor, David Loman should do well at the box office over the Lunar New Year, which sees several Taiwanese movies hitting the big screen to entertain the holiday crowds.

Photo courtesy of Polyface Entertainment Media Group

Photo courtesy of Polyface Entertainment Media Group

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

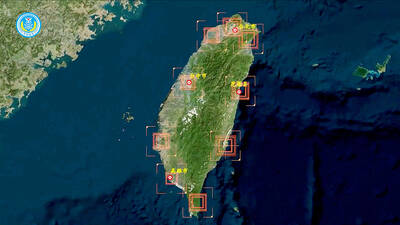

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,