The beautifully-named Orchid Island (蘭嶼) belies a sad truth. Like the fragrant tropical flower that lent this tiny outcrop of land its name, the local language — Yami — is facing extinction. Surrounded by the entirety of the vast Pacific Ocean the increasingly weather-battered island, and its Yami speakers, are now struggling to fend off global forces which could swallow them up whole.

Liao Hui-ling, 37, one of Orchid Island’s only nurses and a member of the indigenous Tao (達悟族) people (known also as the Yami, 雅美族), is sensitive about the loss of her mother tongue.

“Without my language it’s like I don’t have water, and I’m thirsty,” Liao says.

Photo courtesy of Liao Hui-Ling

Liao Hui-ling is just one of three names the married mother of two uses in daily life. To her parents she remains Sinan Matopush, her Aboriginal name. At work she uses her Chinese name and when dealing with the dozens of curious English-speaking tourists she hosts every year on the island, she uses the moniker Teresa. It is a multilingual existence that Liao leads — like many of her compatriots — but it comes at a cost.

“I can speak my own language, but I can’t speak it well. My English is better than my Yami,” concedes Liao.----

However, it is the influence of Mandarin Chinese that poses the greatest threat to her endangered mother tongue, Liao says.

Graphic: Taipei Times

“When kids go to school they learn Chinese. When they study books it’s in Chinese. When they deal with the government it’s in Chinese. How can my language continue to the next generation like this?” she says.

Critically endangered languages

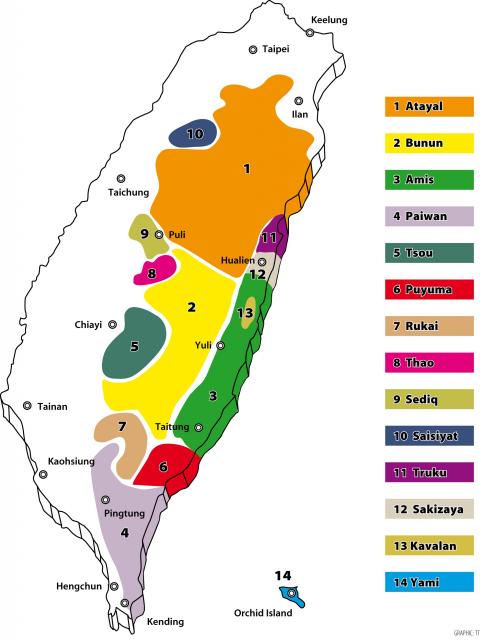

In fact, in Taiwan today all the country’s Aboriginal languages are facing grave threats to their future survival. Many of the spoken forms of the 14 recognized indigenous groups — whose languages and dialects gave birth to the collection of Austronesian languages that are now spoken worldwide by about 300 million people — are at a point of almost total collapse.

When the UN’s global cultural arm UNESCO undertook an evaluation of 24 Taiwanese Aboriginal languages in 2009, it found that nine of them were already extinct. Particularly hard hit are those communities located on the nation’s west coast, including Siraya and Babuza. A further six languages — including Kavalan which is spoken in and around Hualien County and Thao which heralds from Nantou County — are critically endangered. In some cases only dozens of speakers remain.

Even Amis, Puyuma and Paiwan — numerically some of the stronger Aboriginal languages — are struggling and are now listed by the UN body as vulnerable.

language of identity

“There is an idea of a person’s identity and ethnicity in their language,” says Truku-speaking Apay Yuki who is a member of the Taroko tribe. “If you don’t speak it then you don’t know who you are … Language contributes to a person’s identity.”

Yuki, an assistant professor with the Department of Indigenous Languages at National Dong Hwa University (國立東華大學), recently returned to her native homeland to carry out research into the health of her mother tongue. The findings, she says, are distressing.

“You could see that the younger group are showing serious and ongoing language attrition and the local language is being seriously damaged. When people who speak Taroko fluently, generally those aged above 50, are gone then the language is gone,” she says.

Yuki says that the loss of Aboriginal lands combined with years of repression — both at the hands of acquisitive Han Chinese settlers, colonial Japanese forces and the punitive period of Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石) Martial Law era — enacted a terrible toll on indigenous people as a result of which “social structures were changed.”

However, she argues, while the oppression continues to haunt Aboriginal peoples, today’s linguistic threats are different. Waves of migration to cities away from traditional Aboriginal language strongholds as younger people search out work, coupled with a loss of value attached to local tongues, are dealing a double blow to already weakened languages.

Yuki adds that government policy has consistently failed to make the teaching of Aboriginal languages a priority. A 50-minute Aboriginal language class a week, often taught by a non-native speaker, is ineffective, argues Yuki, who also questions how resources are being used.

“There is [government] funding, but I’m not sure how effective it is. The money is a waste … The first thing to do is to really dig out the root problem about why people are not re-learning their languages.”

Bottom up approach

Yuki argues that a “bottom up” approach would improve the re-learning of local languages and says the benefits of speaking the language of your elders is immensely rewarding.

“We are now trying to convey to parents how important it is to speak our languages and what cognitive benefits it brings. Personally, after re-learning my language, I feel — as a family — we are closer, I feel a sense of belonging. I’m proud of being Taroko, it’s an affirmation.”

The person charged with shaping and implementing government policy on Aboriginal languages is Ciou Wun-long (邱文隆), an official at the Council of Indigenous Peoples. The 40-year-old Bunun tribe member, who has headed the department’s Language Section for five years, says reviving Taiwan’s 42 Aboriginal languages and dialects is a “formidable” task.

Ciou cites the 60-year-long ban on local languages, and today’s multi-racial society where there are “limited places where indigenous languages can be spoken,” as key factors explaining the demise of Aboriginal languages.

However, he maintains “there is still hope,” and cites the council’s 2001 Aboriginal Language Skill Certification Examination as a bureaucratic achievement designed to arrest the slide toward extinction.

“In addition to the language proficiency test, Aboriginal dialects have also been included into the school curriculum … [which] has also helped relevant teaching materials come into being, and has helped to cultivate teachers of Aboriginal languages,” Ciou says.

Furthermore, Ciou argues, the council’s drive to establish written systems for indigenous languages has boosted conservation efforts, with 13 dictionaries completed thus far.

However, Ciou concedes that with the number of programs the council is endeavoring to push ahead, government resources are insufficient. “The government only allocates an annual budget of between NT$110 million and NT$120 million into language revitalization, an amount that is inadequate to fund the works the council has been doing,” Ciou said.

By contrast, the government spent over NT$215 million on a two-night rock musical to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Republic of China.

While there may be a growing recognition of the value of local languages at certain levels in government, some argue that there are familiar patterns at work.

Daniel Kaufman, a linguist and a director of the New York-based Endangered Language Alliance explained in a recent email interview that “endangered languages are found throughout the globe, but it is most often disenfranchised ethnic minorities who are most affected”.

Kaufman, an expert in Austronesian languages, says that the loss of Taiwanese Aboriginal languages is like losing branches from the Austronesian family tree as all of the connected languages spoken outside Taiwan can be traced back to a single ancestor language that left the island around 4,000 years ago.

Urban diaspora bridges gap

Kaufman meanwhile says that his agency is increasingly working in cities. “We find that, contrary to expectations, some of the best and brightest speakers of threatened languages are now living in the diaspora. This does not mean that working with diaspora communities can replace working with communities ‘in-situ.’ On the contrary, we find that working with diaspora communities is often a bridge to the home communities. But in an era of increasingly unstable funding, it is imperative that we work with as many communities as possible … if we are to have any impact at all on stemming the tide of language death.”

This model is one that finds a local manifestation through the Bethel Center in New Taipei City. Established over a decade ago by the non-profit Zhi-Shan Foundation (至善社會福利基金會), the center takes care of over 100 Aboriginal children and teaches Aboriginal languages to pupils while also respecting Aboriginal culture. It is an example that has been cited by the Control Yuan and lawmakers as evidence that locally-run facilities targeting Aboriginal people can produce results.

Given the gravity of the situation faced by many languages worldwide, Web titan Google recently helped to set up The Endangered Languages Project. The online resource is a drive to “record, access and share samples of and research on endangered languages, as well as to share advice and best practices for those working to document or strengthen languages under threat.”

Dead languages

However, even those involved in championing the preservation drive concede that by the end of this century half the world’s existing languages will be dead.

Many dismiss languages and their demise as nothing more than “social Darwinism,” anthropologist Mark Turin recently told the UK newspaper The Guardian. “I usually ask them whether they feel the same about all the old churches and buildings … or the plight of species around the world. Our work means we’re helping not only endangered languages to stay with us, but all the culture and history that they denote.”

Orchid Island’s lush, green mountainsides are the last vestige of Taiwan proper before the enormous ocean opens up to its east, an isolated outpost of human habitation that has provided the basis for life, and language, for thousands of years.

Liao Hui-ling is wistful as she reflects on the potential loss of such ancient history within a few short generations.

“Every tribe has a language and it’s a way to connect older and younger generations — language is key to that connection. How can we continue our ceremonies, if we don’t speak our language? Without your language you don’t have your own soul, your identity,” Liao says. “But, right now, our language doesn’t seem that important.”

— Additional reporting by Stacy Hsu

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she