When Arnold Schwarzenegger was governor of California, a reporter asked about the Cohiba label on the cigar Schwarzenegger was smoking.

“That’s a Cuban cigar,” the reporter said. “You’re the governor. How can you flout the law?”

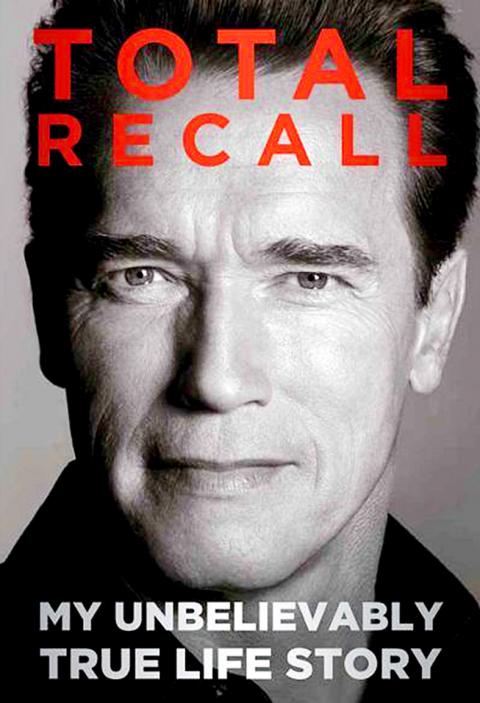

The answer was as good a one-sentence encapsulation of the bodybuilder/entrepreneur/movie star/politician/braggart’s philosophy as all of Total Recall, his 646-page memoir, provides.

“I smoke it because it’s a great cigar,” he said.

This is only one of countless ways Schwarzenegger has prized self-interest throughout his long, glory-stalking and (as he loves pointing out) extremely lucrative career. Total Recall contains nonstop illustrations of how he aims high, tramples on competitors, breaks barriers and savors every victory, be it large or small. Those who mistake Total Recall for a salacious tell-all may not be that interested in how many Mr. Olympia contests he won (seven) or who he beat for a Golden Globe in 1977 (Truman Capote and the kid who played Damien in The Omen).

Let’s get the scandalous stuff out of the way, because Schwarzenegger certainly wants to. About the son he conceived with the family housekeeper, Mildred Baena, in 1996, he says only this: that he had always promised himself not to fool around with the help. That once, “all of a sudden,” he and Baena “were alone in the guesthouse.” And immediately after that: “When Mildred gave birth the following August . . . ”

What Total Recall actually turns out to be is a puffy portrait of the author as master conniver. Nothing in his upward progress seems to have happened in an innocent way.

The book begins with the obligatory description of his Austrian childhood and the fact that he and his brother were forced to do situps to earn their breakfast. He also explains how the bodybuilder photos he pinned up in his room made his mother seek a doctor’s advice. The doctor assured her that these were surrogate father figures, so there was nothing “wrong” with her red-blooded, heterosexual boy.

The book moves on to describe a hair-raising stint in an Austrian army tank unit, where antics included driving one tank into water and trying to drag-race with another. This earned him an early release from service. He went on to win bodybuilding titles in Europe, move to the US, garner the attention of the filmmakers who would feature him in Pumping Iron and land the Hollywood acting role he coveted in Stay Hungry.

When told by an acting coach to summon a sense memory of victory, he says, “I had to explain that actually I was not especially exhilarated when I won, because to me, winning was a given.”

And so it goes, through progress from pedestal to pedestal, until Conan the Barbarian makes him an action star. Schwarzenegger and his co-writer, Peter Petre, had to brush up on the details of his acting career by reading biographies and movie journals; his memory for slights, triumphs and salaries seems more reliable than his memory for work. But one way or another, we learn how raw meat was sewn into his Conan costume for a scene in which he is attacked by wolves. (Sadly, the audio version of Total Recall is not fully read by him. You would have to re-watch the film to hear him say: “Hither came I, Conan, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, to tread jeweled thrones of the earth beneath my feet.” But it might be worth it.)

In 1977 he met Maria Shriver, who would become his wife and enthusiastic helpmate until the matter of Baena and her son came to light. Although Schwarzenegger says that others wrongly imagined that to “marry a Kennedy” was one of his goals, he, too, speaks of their union as an accomplishment. Among many noxious references to his wife are a buddy’s pre-wedding quip (“Oh boy, wait until she hits menopause”) and his way of commissioning an Andy Warhol portrait of her.

“You know how you always do the paintings of stars?” he says he asked Warhol. “Well, when Maria marries me, she will be a star!”

He does not appear to be joking.

When Schwarzenegger was at the height of his movie career, he thought of quip-making as one of his strong suits. (In Commando, about a man whose neck he has just broken: “Don’t disturb my friend, he’s dead tired.”) But he was personable enough to cultivate his Democratic Kennedy in-laws and also grow close to the Republican circle of President George H.W. Bush. He claims to have been included in a decision-making meeting about the initial Gulf War invasion of Iraq.

His account of his own political career is, of course, careful to accentuate the positive. He ran for governor of California in 2003’s recall election even after Karl Rove told him that Condoleezza Rice was being groomed as a future candidate of choice. He emphasizes his centrist credentials as a Republican favoring a social safety net, solar energy and stem cell research but also facing down his state’s three most powerful public employee unions. He claims to have done his best to grapple with the state’s dire budget woes. But he atypically keeps the crowing minimal: “I do not deny that being governor was more complex and challenging than I had imagined.”

This book ends with a not-great list of “Arnold’s Rules.” They are basic (“Reps, reps, reps”), boorish (“No matter what you do in life, selling is part of it”), big on denial (“When someone tells you no, you should hear yes”) and only borderline helpful. When he met Pope John Paul II in 1983, they talked about workouts. The pope rose daily at 5am in order to stick to his regimen. If he could do it, this book says, you can do it, too.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the